Bolero

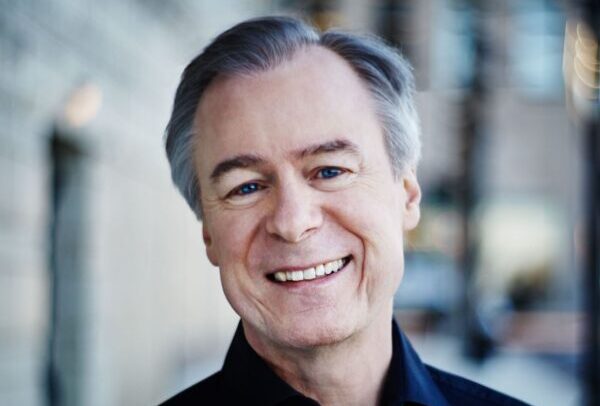

Stéphane Denève, conductor

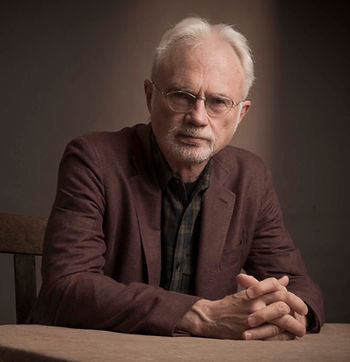

Timothy McAllister, saxophone

HONEGGER Pacific 231 ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine

CONNESSON A Kind of Trane (U. S. Premiere)

ROUSSEL Symphony No. 3 in G minor, op. 42 RAVEL Bolero

Stéphane is taking us on short rides in some very fast machines.

Arthur Honegger stamps our tickets as we board a powerful steam train. John Adams straps us—terrified—into an Italian sports car. Maurice Ravel brings us to a bloodthirsty drama near a Spanish factory. Guillaume Connesson exploits the power and brilliance of a musical machine: the saxophone.

Then there is Albert Roussel. Escaping the sound and fury of this technology, Roussel retreats to his isolated seaside French home to rediscover the old-fashioned symphonic form.

Today, we might agree with Roussel: technology can distance us from our humanity, can lead “to brutality.” But there is evidence that technology helped us become human. Long ago, as we manipulated the natural world—making weapons and tools from stone, developing cooking processes—our brains grew larger, our thinking became more sophisticated.

Is this concert an indictment of inhuman machines, driving us away from ourselves? Or does it celebrate humanity’s ability to innovate and invent?

Pacific 231

ARTHUR HONEGGER

Born March 10, 1892, Le Havre, France

Died November 27, 1955, Paris, France

The first machine is a train.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the industrial revolution changed society forever. Powering this change—taking us across plains and mountains and rivers—was the steam train.

To artists, the train represented modernity, change, the future. Hundreds of composers wrote pieces inspired by these machines, thrilled and terrified by their sound.

Arthur Honegger spent thousands of hours traveling by train as a student in Paris. “I love locomotives passionately,” he wrote. “For me they are living creatures and I love them as others love women or horses.”

Much of his travel was on a class of steam locomotive known in France as “Pacific” or “2-3-1.” The digits refer to the number of axles on the engine: looking from the side, we see two small pilot wheels, then three larger driving wheels, then one small trailing wheel.

Honegger’s Pacific 231 grows slowly, from “the quiet turning-over of the machine at rest,” writes Honegger, to “the sense of exertion as it starts up, the increase in speed and then finally the emotion, the sense of passion inspired by a 300-ton train hurtling through the night.”

The piece was an instant hit. “The audience adored Honegger’s strange new train music,” wrote a journalist of the premiere, “and applauded for nearly seven minutes without pause!” This adulation disconcerted Honegger, who preferred music at its “most serious and austere…I have no taste for the fairground.” He instead linked his piece to an old-fashioned form called the chorale prelude: in Pacific 231, fragments of a melody only come together in the brass at the very end.

| First performance | May 8, 1924, by the Paris Opéra, Serge Koussevitzky conducting |

| First SLSO performance | March 6, 1925, Rudolph Ganz conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 16, 1970, Walter Susskind conducting |

| Instrumentation | piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, bass drum, cymbals, tam tam, tenor drum, strings |

| Approximate duration | 7 minutes |

Short Ride in a Fast Machine

JOHN ADAMS

Born February 15, 1947, Worcester, Massachusetts

The next machine is an Italian sports car.

John Adams’ music is littered with gadgets, engines, devices. There are the player pianos in Century Rolls, the oil tankers of Harmonielehre, the record player in The Chairman Dances, the atom bomb at the end of Dr. Atomic. His music exists at the juncture between old and new, between trembling organic beauty and mechanical precision.

One day, a friend took Adams for a drive in an Italian sports car. He found the experience terrifying, and when he came to write a fanfare on commission from the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, he remembered this short ride: “I had not recovered. [Short Ride] is an evocation of that experience: thrilling and white-knuckle.”

Adams writes:

The piece starts with the knocking of a woodblock, which creates a sort of rhythmic gauntlet through which the orchestra has to pass. We hear fanfare figures in the brass, but in a kind of rat-a-tat, tattoo staccato form, which typifies most of the activity of this very fast orchestral fanfare.

Part of the fun is making these large instruments—the tuba and double basses, and contrabassoon—move. They have to boogie through this very resolute and inflexible pulse set up by the woodblock.

It’s only at the very end that the orchestra feels free—as if it’s the third stage of a rocket that’s finally broken loose of earth’s gravity and is allowed to float. It’s at that moment that we hear the triumphant “real” fanfare music in the trumpets and horns.

| First performance | June 13, 1986, by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas conducting |

| First SLSO performance | November 1, 1996, Marin Alsop conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | December 31, 2017, David Robertson conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 piccolos, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets (2 additional clarinets optional), 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, bass drum with pedal, crotales, glockenspiel, sizzle cymbal, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tam tam, tambourine, triangle, woodblock, xylophone, (2 optional synthesizers), strings |

| Approximate duration | 4 minutes |

A Kind of Trane (U.S. Premiere)

GUILLAUME CONNESSON

Born May 5, 1970, Boulogne-Billancourt, France

Back to trains. Well, a ‘trane. As in, John Coltrane.

Guillaume Connesson draws from every possible artistic world to create his music. He is spurred by books, by art, by contemplation of the universe itself. He is the sum of many musical parts: from French composers like Ravel and Honegger, to American composers like John Adams, to the sounds of disco and hip-hop.

Writing his first saxophone concerto, he recalled the late, great jazz saxophonist and composer John Coltrane. Coltrane’s playing pushed the limits of instrumental virtuosity, producing what have been called “sheets of sound.” He took music to unknown realms with albums that aimed for a sort of spiritual transcendence.

A Kind of Trane is an homage to Coltrane’s albums and to his musicianship. Soloist Tim McAllister says that Connesson knows how to write for the instrument. “He was raised amongst the elite [saxophone] players of the French school,” he says. “And he has an affinity for modern American jazz.”

The saxophone is a complex piece of musical machinery. Made from some 300 hand-crafted parts, it was invented in the 1840s, a time of instrumental innovation. Adolphe Sax was looking for a sound that bridged the divide between bright brass and mellow woodwind.

McAllister has toured Connesson’s concerto across the globe. He says that stamina is a major challenge in the work: switching between instruments, the demand for fast and sustained playing at very high volume.

Although the work is a homage to John Coltrane, “it really is a survey of all the influences on Connesson’s compositional voice,” says McAllister, “from Ravel’s density and Debussy’s colors to John Adams’s rhythms and the soaring ballads of jazz icons of yesteryear.”

First movement: soprano saxophone. Coltrane’s album A Love Supreme has been called a “struggle for purity, an expression of gratitude.” Connesson’s solo saxophone captures some of Coltrane’s wild flights of freedom, while the tight orchestral groove builds to a forceful climax.

Second movement: alto saxophone. Coltrane’s album Ballads may have been a response to critics who thought his music too complex. Coltrane’s quartet arrived at the studio with songs they didn’t yet know, discussed their plan, then recorded the album. Connesson responds to Ballads with gentleness, with calm. McAllister says that this music “melts my heart each time with its beauty.”

Third Movement: soprano saxophone. Man versus the machine. Connesson contrasts the freedom of Coltrane’s playing with what he thinks is the “robotic” nature of today’s dance music. The finale includes “some of the hardest music ever composed for soprano saxophone,” says McAllister. “It is quite the workout!”

First performance, version for solo saxophone and wind ensemble: July 2015 at the World Saxophone Congress and Festival in Strasbourg, France, with Joonatan Rautiola (mvmt. 1), Jean-Yves Fourmeau (mvmt. 2), and Nicolas Prost (mvmt. 3) as soloists

| First performance, and U.S. premiere of version for solo saxophone and orchestra | This weekend’s concerts |

| First SLSO performance | February 4, 1949, Suite No. 2, Vladimir Golschmann conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 6, 2016, Gilbert Varga conducting excerpts from the first two concert suites |

| Instrumentation | piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, bass drum with pedal, chimes, claves, cymbal with buttons, glockenspiel, guiro, high hat, marimba, mark tree, sandpaper, shaker, snare drum, 2 suspended cymbals, tam tam, 3 tom toms, triangle, vibraphone, wood block, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 22 minutes |

Symphony No. 3

ALBERT ROUSSEL

Born April 5, 1869, Tourcoing, France

Died August 23, 1937, Royan, France

The next machine is…well…the next machine is no machine at all.

Albert Roussel fled city chaos, fled the sound of factories, fled Italian sports cars. “The invasion of mechanization,” he wrote, can often lead “to brutality.” Roussel lived his beliefs, making his home in Vasterival, an idyllic village nestled between woods and ocean in northern France.

By the time he was in his 50s, Roussel had found his mature musical voice. As a young man he spoke the language of fellow French composers like Debussy and Ravel. As a thirty-something, his music gathered detail, complexity. Now, Roussel spoke with simpler sounds.

He put his hope in what he called “cleaner lines, more forthright statements, more vigorous rhythms.” And he noticed that music around him was changing too. “Programmatic compositions and descriptive symphonic poems seem to be abandoned in favor of classical forms, where music alone reigns.”

The Third Symphony was written for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. For a composer who had never experienced any sort of international success, the Third Symphony was a surprise-hit. After its Boston premiere, the Globe critic wrote that if Mozart had still been composing, he would write like Roussel.

Roussel thought the symphony was “the best thing that I have done.” He grips us by the scruff of the neck right away, with a first movement that is forceful, vigorous—a tempest that only occasionally finds calmer waters.

Solo winds introduce a slow second movement that could be a funeral oration: alternately sorrowful, passionate, strident, a little quirky. The short third movement whirs and spins around the orchestra, giving every section a chance to join the fun.

Continuing the high spirits, Roussel’s final movement feels like we’ve stumbled on a street festival in a busy city. Children play, vendors yell, bands compete for attention. A violin solo offers a quiet moment of reflection before the hijinks begin again.

| First performance | October 24, 1930, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Serge Koussevitzky conducting |

| First SLSO performance | November 31, 1951, Vladimir Golschmann conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | November 8, 1981, Erich Leinsdorf conducting |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (2nd and 3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, tam tam, tambourine, triangle, 2 harps, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 23 minutes |

Bolero

MAURICE RAVEL

Born March 7, 1875, Ciboure, France

Died December 28, 1937, Paris, France

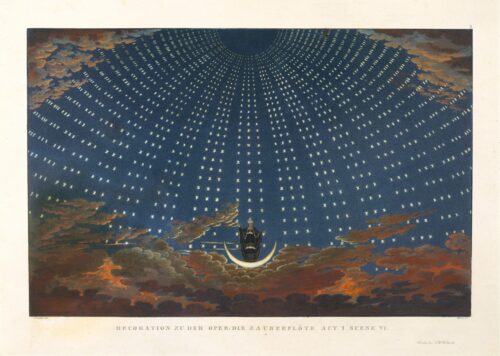

The final machines are those of a factory.

By the late 19th century, factories across Europe had revolutionized the production of goods. France was slow to turn to industrialization, and far fewer factories operated in the country. Where they did exist, pay was terrible, working conditions were abhorrent.

Ravel grew up around factories. “In my childhood I had a great interest in mechanical things,” he wrote. His father was a civil engineer, and Ravel loved “going over factories and seeing vast machinery at work. It is awe-inspiring.”

When approached to write a new ballet score, Ravel set a story of jealousy and retribution in the shadow of a factory. The scenario was eventually rejected, but Ravel’s machine-like music remains.

The ballet was set in Spain, a country that provided Ravel with inspiration throughout his career. “I have always had a predilection for Spanish things,” he wrote. “I was born near the Spanish border, and my parents met in Madrid.”

By the time he wrote the ballet, Ravel had never stepped foot in Spain. Bolero mimics sounds he knew: guitars (in the plucked strings), castanets (in the snare drums), and “tunes of the usual Spanish-Arabian kind.”

The Spanish boléro emerged in the 18th century as a mix of folk and classical dances. Like Ravel’s Bolero, the traditional dance has three slow beats in a bar, but Ravel’s version takes liberties with the rhythm. “In reality,” he wrote, “there is no such boléro.”

For the French, Spain was considered exotic. It lay close to North Africa, and Africa was—according to one prominent writer of the time—“half Asiatic.” Many today find such attitudes problematic, but Ravel’s audiences were seized by the thrill of “alien” lands.

Bolero is a vast musical machine. A simple rhythm is played again and again on snare drum, while soloists snake above, playing two sinuous melodies. Standard orchestral wind instruments begin (flute, clarinet, bassoon), then more distant cousins continue (oboe d’amore, tenor and soprano saxophone).

The music gathers steam. One soloist becomes a duet, becomes a trio, becomes a full orchestral section. Another snare drum joins the first. At its peak, the din is deafening. Trombone whoops and gong strikes herald the end. But is this a factory, or warfare?

| First performance | November 20, 1928, by the Paris Opéra, conducted by Walther Straram |

| First SLSO performance | February 28, 1930, Eugene Goossens conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | November 26, 2017, Jun Märkl conducting |

| Instrumentation | piccolo, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling oboe d’amore), English horn, 2 clarinets (2nd doubling E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 3 saxophones (sopranino, soprano, and tenor), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, 2 snare drums, tam tam, harp, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 13 minutes |

Tim Munro is the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra’s Creative Partner. A writer, broadcaster, and Grammy-winning flutist, he lives in Chicago with his wife, son, and badly-behaved orange cat.