Peter and the Wolf (May 7-9, 2021)

Program

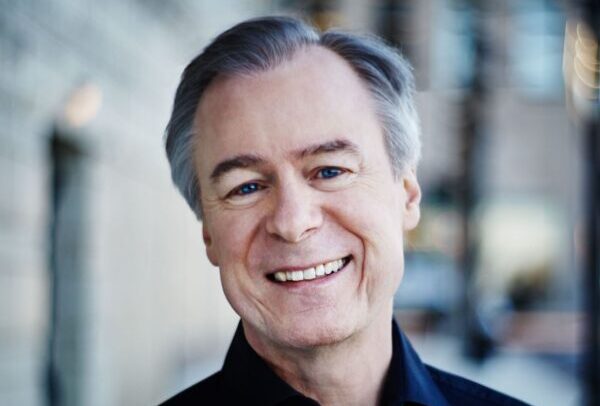

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Alicia Revé Like, narrator

Antonín Dvořák, arr. Michi Wiancko

Songs My Mother Taught Me, op. 55, No. 4 (1880)

Charles Ives, arr. Michi Wiancko

Songs My Mother Taught Me (1895)

Sergei Prokofiev

Peter and the Wolf, op. 67 (1936)

Igor Stravinsky

- Puclinella Suite (1922)

- Sinfonia (Ouverture)

- Serenata—

- Scherzino: Allegro; Andantino

- Tarantella—

- Toccato

- Gavotta con due variazioni

- Vivo

- Minuetto; Finale

Program Notes

By Tim Munro

Stéphane on this program

From an interview with Stéphane Denève. Stéphane’s responses have been edited for length and clarity, and questions have been removed.

This program is a breath of fresh, youthful air.

Music connects with our inner child. I don’t think that some pieces are for adults, and some pieces are for children. Great art has the power to speak to all parts of our life.

Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf was the second piece I conducted. At the age of fourteen I prepared a youthorchestra for a performance conducted by a mentor. The piece is very special to me.

The songs our mothers sing to us as babies are so important—they are often the first sounds we hear. We play two settings of the same poem, “Songs my mother taught me,” by Antonin Dvořák and Charles Ives.

After the horrors of the First World War and the 1918 flu pandemic, composers reached into the music of the past. It may have been an escape from reality—a way to make things brighter, more hopeful.

Igor Stravinsky’s captures the spirit of several 18th century composers and others in Pulcinella. He treats them with such respect, creating such tender and charming music.

Songs My Mother Taught Me

both versions arranged by Michi Wiancko

Antonín Dvořák

Born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, Czechia

Died May 1, 1904, Prague, Czechia

Charles Ives

Born October 20, 1874, Danbury, Connecticut

Died May 19, 1954, New York, New York

Parent-child bonding happens in several ways. It is communicated through touch and gaze. But it also carried through song: the lullabies, rhymes, and playful melodies our caregivers sing to us.

In “Songs My Mother Taught Me,” Czech poet Adolf Heyduk considers how this practice is passed from one generation to the next:

- Songs my mother taught me in the days long vanished,

- Seldom from her eyelids were the tear drops banished.

- Now I teach my children each melodious measure;

- Often tears are flowing from my memory’s treasure.

Antonín Dvořák was deeply influenced by his native Czech and Slovak folk traditions. When he came to set Heyduk’s poem, Dvořák inhaled his motherland deeply, breathing out the melodies and rhythms of home.

Fifteen years later, a young New Englander named Charles Ives wrote his own setting of the same poem. Aged 21, Ives was a rule-breaker, a pathfinder. But in “Songs My Mother Taught Me,” he took a different approach.

Instead of chords that clash, a solo voice floats above tolling bells. We are transported to the haze of an idealized past.

Ives’ setting is dedicated to his mother, who is almost invisible in the historical record. Perhaps this song allowed Ives to return to his earliest music teacher: his mother’s voice.

Songs Stéphane’s mother taught him

I asked my mother what she sang to me when I was a baby. It is touching—she sang to me the very same comptines (rhyming songs for babies) that I sang to my daughter, Alma.

Here are a selection of the songs she sang:

“Do do, l’enfant do.” (Do is the beginning of the word dormira: “will sleep”)

“Fais do do, Colas mon petit frère.” (Go to sleep, Colas, my little brother)

“Au clair de la lune.” (By the light of the moon)

“Frère Jacques.” (An ultra-famous (and Mahlerian!) song that needs no introduction!)

“Ainsi font, font, font les petites marionnettes” (They go like this, this, this, the little puppets)

“Alouette gentille alouette” (Lark, sweet lark)

Voilà. What a trip down memory lane…”

Dvorak’s Songs My Mother Taught Me

| First performance | Unknown |

| First SLSO performance | Of another version, February 20, 1955, Gustave Haenschen conducting. Of this version, these concerts. |

| Most recent SLSO performance | Of another version, June 24, 1972, Walter Susskind conducting |

| Instrumentation | Clarinet and strings |

| Approximate duration | 4 minutes |

Ives’ Songs My Mother Taught Me

| First performance | Unknown |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | Flute and strings |

| Approximate duration | 3 minutes |

Peter and the Wolf

Sergei Prokofiev

Born April 23, 1891, Sontsivka, Ukraine

Died March 5, 1953, Moscow, Russia

Children loved to play with Sergei Prokofiev. He reveled in their imaginative worlds, loved telling fairytales, and would often leave them laughing heartily.

Natalia Satz, director of the Moscow Children’s Musical Theater, saw this childlike quality in Prokofiev. “If he liked something,” she wrote, “he liked it a lot. If he didn’t like it, he didn’t like it at all. He spoke directly, enthusiastically, even sharply.”

When Prokofiev moved home to Soviet Russia in 1936, artistic purges raged. He toed the party line, writing what were considered “heroic and constructive” works for adults. He also composed music for the most important and impressionable audience in Soviet Russia: children.

Satz thought the childlike Prokofiev would be a perfect composer for young audiences. The two met and discussed an original story: there would be animals, and at least one human. Prokofiev wrote his own script.

At the center is “pioneer” Peter. Pioneers were Russian boy scouts, but had a political edge: joining the pioneers was the first stepping-stone to becoming a member of the Communist party.

Even so, Prokofiev’s story doesn’t line up with any political belief system. Peter is curious and strong-willed. His world is small, but he isn’t afraid to challenge authority. His goal is simple: to right the wrongs he sees in the world.

| First performance | May 2, 1936, by the Moscow Philharmonic |

| First SLSO performance | November 9, 1939, Vladimir Golschmann conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 23, 2020, Gemma New conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, tenor Narrator, flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, 3 horns, trumpet, trombone, timpani, percussion (bass drum, castanets, cymbals, snare drum, suspended cymbal, tambourine, triangle), strings |

| Approximate duration | 25 minutes |

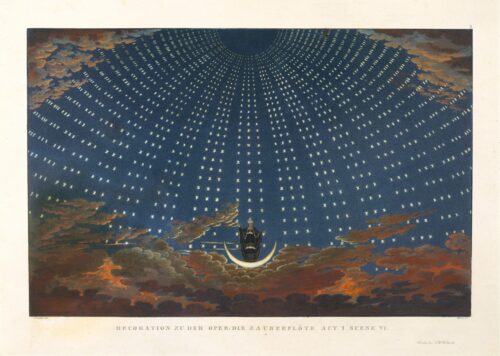

Pulcinella Suite

Igor Stravinsky

Born June 17, 1882, Lomonosov, Russia

Died April 6, 1971, New York, New York

The character of Pulcinella cuts a grotesque figure. In 17th century Italian satire, he swaggers about the stage, hump-backed and hook-nosed, defying authority with rude squawks.

“I often went to the open-air theatre,” wrote choreographer Léonide Massine. “I was intrigued by the grotesque masks and jerky, loose-limbed movement. I found myself wondering how I could transform them into balletic form.”

Massine’s creative spark would bring together an extraordinary collection of artists: theater producer Sergei Diaghilev, artist Pablo Picasso, conductor Ernest Ansermet. And composer Igor Stravinsky.

Stravinsky was a late addition. When asked to make orchestral arrangements of almost-forgotten 18th century music, he wrote, “I wasn’t the least bit excited. I thought [Diaghilev] must be deranged.”

Then he opened the old scores. And, “I fell in love.” The pieces ranged from absurd comic operas to perky chamber music to virtuoso harpsichord pieces. Some were by Giovanni Pergolesi, some by more obscure composers.

Stravinsky tinkered. Soon the project grew, and, rather than making simple arrangements, “I’m rewriting each piece,” he wrote, speaking these musical voices aloud “in my own accent.”

The ballet’s story has something for everyone: games of seduction, disguises and doubles, an attempted murder, and a false resurrection. And, as finale, a triple wedding.

Pulcinella’s music hums with childlike energy. String harmonics glisten, bassoons buzz, a solo double bass laments, a trombone stumbles. The finale splashes cool spring water on your face.

| First performance | December 22, 1922, by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Monteux conducting |

| First SLSO performance | February 27, 1931, Georg Szell conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 25, 2010, Pinchas Zukerman conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (second doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, strings |

| Approximate duration | 24 minutes |

Tim Munro is the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra’s Creative Partner. A writer, broadcaster, and Grammy-winning flutist, he lives in Chicago with his wife, son, and badly behaved orange cat.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.