Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto (April 19-21, 2024)

Program

John Stogårds, conductor

Marie-Ange Nguci, piano

Jean Sibelius

- Rakastava (The Lover), op. 14

- The Lover

- The Path of the Beloved

- Good Night! . . . Farewell!

Ludwig van Beethoven

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major, op. 19

- Allegro con brio

- Adagio

- Rondo (Molto allegro)

- Marie-Ange Nguci, piano

- Intermission

Per Nørgård

Lysning (Glade)

Jean Sibelius

Symphony No. 7 in C major, op. 105

Program Notes

John Storgårds has been a frequent visitor to the SLSO since his debut with the orchestra in 2012, conducting music that has ranged from Joseph Haydn and Johannes Brahms to contemporary creations by Thomas Adès and Helen Grime, while championing the works of Carl Nielsen and Finnish countryman Jean Sibelius.

For this week’s concerts he’s devised a program that’s especially close to his heart. Framing the final installment in this season’s Beethoven piano concerto cycle are two works by Sibelius and an exquisite miniature by a friend, the Danish composer Per Nørgård.

The concert opens with music that’s a first for the SLSO, but which has long enchanted audiences: Sibelius’s tender and bittersweet Rakastava. This music began life as a “second-best” choral work but found real success when revised as a piece for string orchestra (with some help from a timpanist). After that, Sibelius would frequently program it alongside his symphonies, just as Storgårds has done.

With Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 2, we come to the end of a concerto cycle with a difference. Typically, such cycles feature a single soloist in a compressed timeframe. Instead, Music Director Stéphane Denève has spread the concertos across the season, featuring varied, and often younger, voices from around the world. This week, Albanian-born French pianist Marie-Ange Nguci makes her SLSO debut.

Between the Viennese “woods” of Beethoven’s concerto and the Nordic “forest” of Sibelius’s final symphony is a literal musical “glade” (Lysning in Danish) by Nørgård that creates the aural equivalent of dappled light, alternating between darker and brighter sections. This is another SLSO first and another demonstration of the astonishing range of colors that our string section can achieve.

Lysning makes the perfect introduction to Sibelius’s Seventh Symphony. It’s organised in a single movement, but even so, there’s internal contrast and variety as Sibelius sets up the same powerful alternations between darkness and light that you’ll hear in Nørgård’s music.

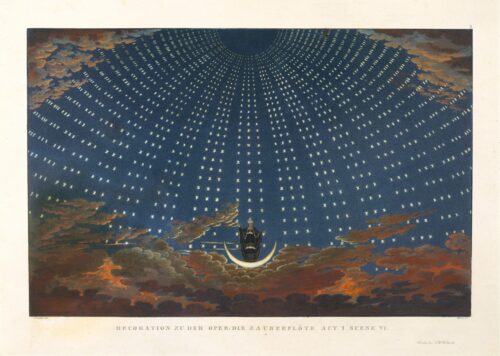

Rakastava (The Lover)

Jean Sibelius

Born 1865, Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

They say no one ever remembers the runners up, only the champions, and that might be true in sport, but in music posterity often takes a different view. Sibelius’s Rakastava was composed as a choral work for a competition organized by the YL Male Voice Choir of Helsinki University in 1894. It came second. Today, in its revised form for chamber orchestra, it’s regarded as a minor masterpiece.

The text of the original version came from a collection of Finnish lyric poems, Kanteletar, and fell into four sections: “Where is my beloved?” then “Here my darling has walked,” and a pair of songs for a night-time meeting and the inevitable farewell. The poems set the mood: yearning, luminous, graceful, and mournful.

Two decades later, Sibelius revised the music to create a new, instrumental work. He expanded on the musical themes of the original, but in ways that are wholly determined by the sounds and techniques of a string orchestra, to which he added timpani and a triangle. This is no longer music you could sing, even though it has lost none of its lyrical character.

The subtle harmonies of the first movement (The Lover) give it a floating ethereal quality. Long, soft drum rolls create fleeting interruptions. The Path of the Beloved has the feeling of perpetual motion—rapid notes in the hushed melody and a plucked accompaniment. Listen for the triangle, which is given its only notes to play in six bell-like taps just before the end. The third movement (Good Night!…Farewell!) reveals a trace of the original: the tenor solo from the choral version becomes a poignant solo for violin in this melancholy and mysteriously atmospheric music.

Abridged from a note by Yvonne Frindle © 2024

| First performance | Rakastava was first heard in 1894 in an arrangement for male chorus and strings; the string orchestra version was premiered on March 16, 1912, the orchestra of the Helsinki Philharmonic Society conducted by the composer |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | strings, timpani (doubling triangle) |

| Approximate duration | 12 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 2

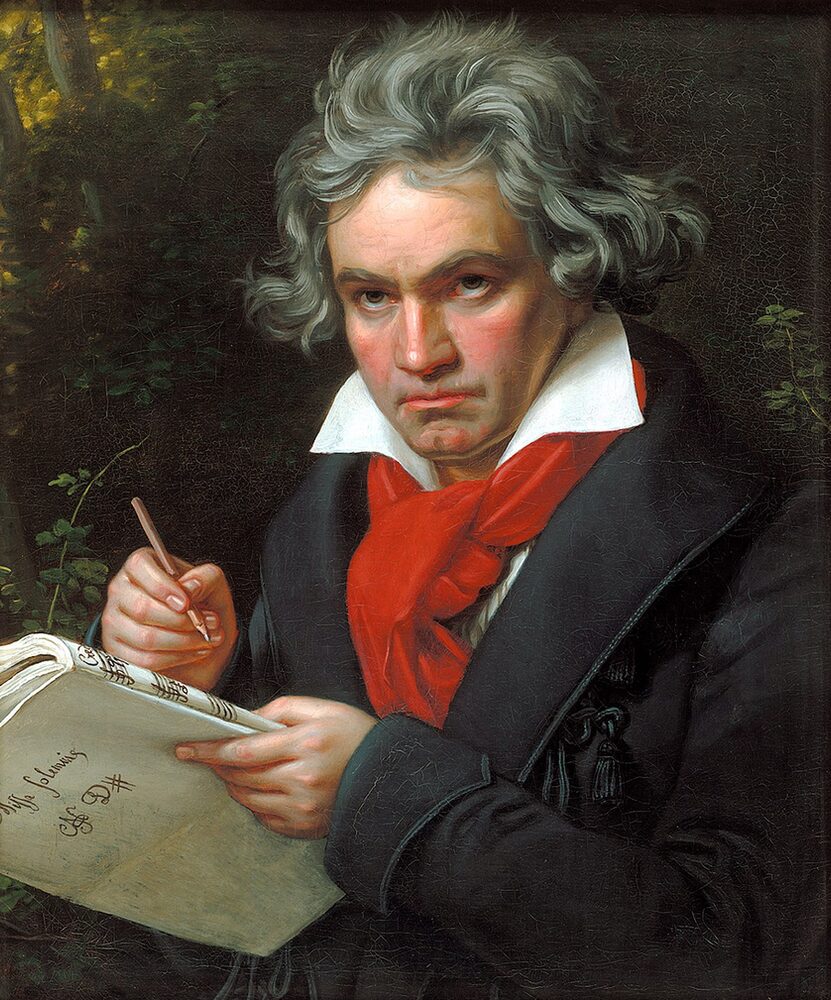

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died 1827, Vienna, Austria

Though officially known as “No. 2,” this piano concerto is the first mature concerto that Beethoven completed, and it was almost certainly the concerto with which he made his Viennese public debut in March 1795. (The concerto known as “No. 1” was simply published first.) Some of the music in the concerto can be traced back to Beethoven’s teenage years in Bonn. Much like a painting in progress over several years, Beethoven kept revising the score during his first decade in Vienna, whenever new opportunities for performance arose, most radically for concerts in Prague and Vienna in 1798. He even abandoned an earlier version of the rondo-finale, writing an entirely new movement, and these periodic efforts to perfect it were partly to blame for the delay in its appearance. In 1801 he offered it to the publishing firm of Hoffmeister for a small sum because as an early work, he said, “I do not consider it one of my best concertos.”

Beethoven needn’t have slighted the piece so. Although not the equal of his later works in power and scope, it is nevertheless a beautiful and skillfully executed composition. In style and spirit it is close to the concertos of Mozart, yet it clearly bears the stamp of Beethoven’s compositional thinking.

The opening movement (Allegro con brio) is spacious and begins with a theme that speaks the language of the Classical period with beautiful fluency. The piano later enters and takes charge with real diplomacy, uncovering new possibilities in the material presented by the orchestra—and tempts the ensemble to try out a brand-new theme. The orchestration is relatively minimal—no clarinets, trumpets, or timpani—which allows for intimate dialogue between the soloist and orchestra.

The first movement of a Classical concerto can strike a wide variety of poses: grandstanding heroism, for example, or, as Beethoven does here, a kind of comic panache, flowing with gentle melody and perhaps even a touch of subversive wit at convention—such as the piano obediently ceding the spotlight back to the orchestra after its big cadenza. Here, the soloist grants the other players a very abbreviated final say, as if they had almost been forgotten, lost in the brilliance of invention during the cadenza.

The cliché of Beethoven as a keyboard-smashing firebrand is impossible to square with the profoundly introspective Adagio. This is just the sort of rapt, drawn-out musical dream that Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny had in mind when describing the spellbinding effect of his piano improvisations.

In the first two movements, Beethoven signs his own name over Mozart’s concerto archetype. The teasing, tricky shape of the theme in the rondo-finale, however, is close in spirit to the vigorous humor Beethoven clearly admired in Haydn. The piano soloist and orchestra collude to bring this comedy to a witty conclusion.

Adapted from notes by Thomas May © 2020

| First performance | Probably March 29, 1795, in Vienna; Beethoven played the solo part, most likely conducting from the piano |

| First SLSO performance | October 23, 1948, Vladimir Golschmann conducting with William Kapell as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 1, 2020, Nicholas McGegan conducting, Seong-Jin Cho as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo piano, flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, strings |

| Approximate duration | 30 minutes |

Lysning (Glade)

Per Nørgård

Born 1932, Dentofte, Denmark

The first thing to know about Per Nørgård’s Lysning is that he chose the title (as is his custom) after having composed the work. The title is a reflection of his own subjective experience of the result, rather than a theme or image directing the creative process.

Nørgård explains that the title—in English a “glade” or perhaps a “clearing”—highlights the way in the character of the music shifts between dark and lighter or brighter sections, just as you might experience when emerging from a forest into an open glade. As an existing example of “light” in music, he points to the second movement of Sibelius’s Rakastava: The Path of the Beloved, “where there are constant alternations between light and dark.”

“The concept of light includes (for me) a becoming, or rather an appearance, seen in relation to a darker background,” writes Nørgård. In other words, this “passage” for string orchestra adopts a musical equivalent to the chiaroscuro technique of Renaissance and Baroque artists, demonstrating that light is never so powerfully portrayed as when it emerges from darkness.

Nørgård also explains “there is a balance between the number of darker and lighter sections, as each ‘light’ section presents the same material as the ‘dark’ section before it—but heard with different instrumental colors and nuances.” One reviewer has compared this to a “black and white mirror” of the musical ideas. Nørgård’s coloristic effects include beautiful string techniques such as the use of mutes and gently touching the strings with the fingers to create flute-like harmonics, contributing to a sound that is at once radiant and ephemeral.

About the composer

Per Nørgård (pronounced pair ner-gaw), approaching 92, is a quietly influential voice in Danish music, through both his compositions and his technical and philosophical writings. But, until quite recently, his music was not much performed in the United States, although he reached a wider audience in 1987 through his soundtrack for the Oscar-winning film Babette’s Feast.

His early influences included Finnish composer Jean Sibelius and fellow Dane Carl Nielsen. Further afield, he found inspiration in the minimalist music of his American contemporaries Terry Riley and Philip Glass, as well as more unexpected sources such as Hawaiian chant. But his style, as reflected in Lysning, is distinctly personal. It follows, in part, an original compositional system known as “infinity series,” based on principles of repetition, variation and the superimposition of musical layers. But despite strict theoretical underpinnings, his music is lucid and lyrical, even romantic in character, and often kaleidoscopically colorful—much in the same way that fractal geometry is both mathematical and aesthetically appealing.

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

| First performance | July 16, 2007 in Åkirkeby on the Danish island of Bornholm, Morten Ryelund conducting DRUEN (Danish Radio Youth Ensemble) |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | strings |

| Approximate duration | 5 minutes |

Symphony No. 7

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius’s Symphony No. 7 is the last, briefest, and most unusual of the works for which the composer’s admirers proclaim him the greatest symphonist of the 20th century. It is perhaps the most beautiful as well. Avoiding the grand gestures of some of Sibelius’s earlier works in this form, Symphony No. 7 makes its effect through a compelling journey of thematic ideas—ideas whose recurrences and evolution seem dictated by a dynamic inner life of their own.

This symphony went through a long creative gestation, during which time it changed form considerably. In a letter written in 1918, Sibelius described the work, which he must have already begun composing, as being in three movements, though he added, “the plans may be altered according to the development of the musical ideas. As usual, I am a slave to my themes and submit to their demands.” By the time it was completed, some six years later, the piece had been transformed into a composition in one movement. Sibelius seems initially to have been reluctant to call this work a symphony, and in March 1924 he conducted its premiere under the title “Fantasia sinfonica.” But when the score was published, the following year, the composer had again changed his mind, admitting the work to the ranks of his symphonies.

Despite its compact single-movement form, the symphony offers a satisfying variety of themes, moods and textures. Its initial measures present a pair of important ideas: a scale rising quietly but firmly in the strings and, moments later, a brighter melodic figure in the woodwinds. These sounds give rise to a beautiful, prayer-like passage for the strings. As the music grows more confident and the winds rejoin the proceedings, a ringing call emerges from the first trombone, and we presently hear again the scale figure of the opening measures.

Its main thematic materials thus established, the symphony soon accelerates to a more lively scherzando section. But the genial character this music brings does not last long. Soon churning lines in the strings produce ominous echoes from the brass. The music presses to a climax, then briefly recalls the light figuration of the scherzando passage. Now Sibelius launches into a joyous section that functions as the work’s finale. Before this concludes, we hear again the rising scale figure, the stirring trombone call, and a reminiscence of the devout string melody of the work’s initial section. The music grows wonderfully quiet before swelling to its conclusion.

| First performance | March 24, 1924, in Stockholm, conducted by composer |

| First SLSO performance | January 14, 1938, Vladimir Golschmann |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 10, 2010, David Robertson conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 22 minutes |

Artist

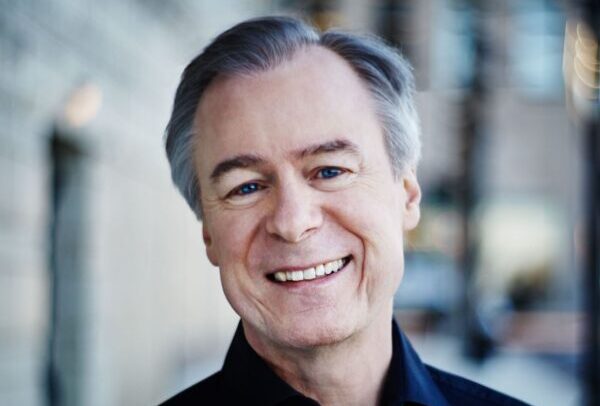

John Storgårds

John Storgårds has a dual career as a conductor and violin virtuoso and is widely recognized for his creative flair for programming as well as his rousing yet refined performances. He is Chief Conductor of the BBC Philharmonic and Principal Guest Conductor of the National Arts Centre Orchestra Ottawa, and has been Artistic Director of the Lapland Chamber Orchestra for more than 25 years, earning widespread critical acclaim for the ensemble’s adventurous performances and award-winning recordings. Previous titles include Chief Conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra (2008–15) and Artistic Partner of the Munich Chamber Orchestra (2016–19). Next season he will take up the post of Chief Conductor of the Turku Philharmonic Orchestra, Finland.

As a guest, he appears with the Berlin Philharmonic, all the major Nordic orchestras, and other leading orchestras throughout Europe; the BBC Symphony and London Philharmonic orchestras; and major orchestras in Australia and Japan. In the U.S. he has conducted the Boston, Chicago, and Detroit symphony orchestras, New York Philharmonic, and the Cleveland Orchestra.

His vast repertoire includes the symphonies of Sibelius, Nielsen, Bruckner, Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann. He also regularly performs premieres and many works are dedicated to him, including Per Nørgård’s Symphony No. 8 and Kaija Saariaho’s Nocturne for solo violin.

Highlights of the 2023/24 season included two appearances at the BBC Proms with the BBC Philharmonic, as well as numerous return engagements, including the Oslo Philharmonic, Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, and Helsinki Philharmonic, appearing as both conductor and soloist.

His award-winning discography includes cycles of symphonies by Sibelius and Nielsen and three volumes of works by American George Antheil, and he is currently recording the late symphonies of Shostakovich with the BBC Philharmonic. Last year he and the BBC Philharmonic were nominated for Gramophone magazine’s Orchestra of the Year Award.

John Storgårds studied violin with Chaim Taub and was concertmaster of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Esa-Pekka Salonen, before studying conducting with Jorma Panula and Eri Klas. He received the Finnish State Prize for Music in 2002 and the Pro Finlandia Prize in 2012.

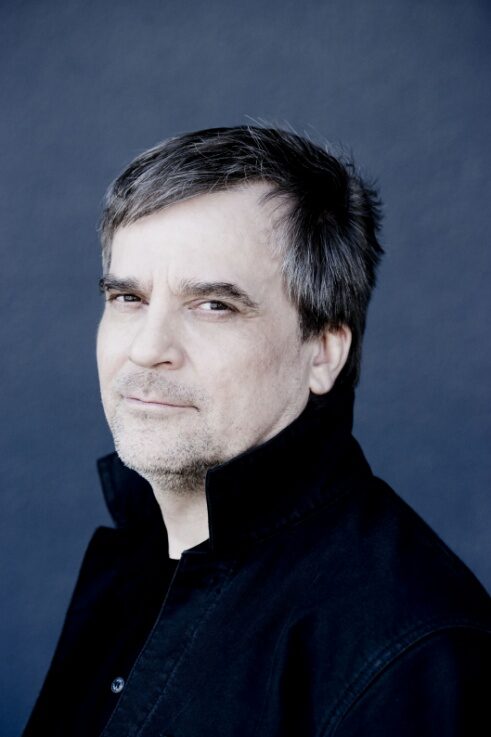

Marie-Ange Nguci

Marie-Ange Nguci’s talents were recognized early on when, aged 13, she won her first competition, the 2011 Lagny-sur-Marne International Piano Competition. That same year the Franco-Albanian pianist was accepted into Nicholas Angelich’s class at the Paris Conservatoire.

She has since positioned herself as an outstanding young artist with an extensive and diverse repertoire, and recent performance highlights have included engagements with such orchestras as the NHK Symphony Orchestra (Japan), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and Danish National Symphony Orchestra, as well as major orchestras throughout France. She has performed in venues such as the Vienna Musikverein, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Zurich Tonhalle, and Sydney Opera House, and in 23/24 was artist-in-residence with the Basel Symphony Orchestra.

In addition to these her first performances with the SLSO, highlights of the current and future seasons include performances with the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, and Orchestre National de Lyon, as well as the Minnesota Orchestra and Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

Her debut CD, En Miroir, featuring piano works by composers best known as organists and improvisers (César Franck, J.S. Bach, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Thierry Escaich) brought her wide attention and critical acclaim in 2018, and was awarded a coveted Choc de Classica.

Her musical gifts are matched by a deep intellectual curiosity and she holds degrees in Musicology, Musical Analysis, and Music Pedagogy (Paris Sorbonne, Paris Conservatoire), a performance diploma in ondes martenot, and an MBA in Cultural Management, as well as studying conducting at Vienna’s University of Music and Performing Arts.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.