Prokofiev and Childs (February 6-7, 2026)

Program

February 6-7, 2026

- Xian Zhang, conductor

- Steven Banks, saxophone

Reena Esmail (b. 1983)

- RE/Member

Billy Childs (b. 1957)

- Diaspora – Concerto for saxophone and orchestra

- Motherland

- If We Must Die

- And Still I Rise

Steven Banks, soprano and alto saxophones

Intermission

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1853)

- Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, Op. 100

- Andante

- Allegro marcato

- Adagio

- Allegro giocoso

RE/Member

Reena Esmail

Born 1983, Chicago, Illinois

The premiere of RE|Member in 2021 marked an experience that was echoed by orchestras and audiences throughout the US: the members of the Seattle Symphony were performing together for the first time in 18 months following the disruptions and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic. For Reena Esmail, the Seattle Symphony’s Artist in Residence that season, RE|Member offered a chance to explore what the world had gone through. The work had been intended to open the 2020/21 season, capturing that feeling of returning to the concert hall after the summer— “a change of season, a yearly ritual”—but it was to take on much more weight, charting the return “to a world forever changed.”

“I wanted this piece to feel like an overture,” said Esmail at the time, “and my guides were two favorites: Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and Bernstein’s Candide. Each is breathless and energetic, with pockets of intimacy and tenderness. Each contains many parallel universes that unfold quickly. Each has beautiful, memorable melodies that speak and beckon to one another. I strove for all of this in RE|Member.”

The title is a multifaceted one, and by happy coincidence it also allowed Esmail to “sign” the work with her initials, RE, something she noticed only after the fact. The piece connects two meanings of the word “remember,” she explains.

“Firstly, the sense that something is being brought back together. The orchestra is re-membering, coalescing again after being apart. The pandemic will have been transformative: the orchestra is made up of individuals who had a wide variety of experiences in this time. And they are bringing those individual experiences back into the collective group. There might be people who committed more deeply to their musical practice, people who were drawn into new artistic facets, people who had to leave their creative practice entirely, people who came to new realizations about their art, career, life. All these new perspectives, all these strands of thought and exploration are being brought back together.

“And the second meaning of the word: that we don’t want to forget the perspectives which each of these individuals gained during this time, simply because we are back in a familiar situation. I wanted this piece to honor the experience of coming back together, infused with the wisdom of the time apart.”

Over the past four years, RE|Member has flourished, with repeat performances and fresh versions ranging from duet to concert band. Among its musical highlights is the wistful and evocative solo for unaccompanied oboe that begins the piece and returns at the end as an oboe duet after what has been described as a “rambunctious, nostalgic romp” for the orchestra.

Adapted from a note by Raff Wilson © 2021

By kind permission of the Seattle Symphony.

About the composer

Reena Esmail is an Indian American composer who works between the worlds of Hindustani and Western classical music. A graduate of Juilliard and the Yale School of Music and a Fulbright recipient, she lives in Los Angeles, and since the premiere of RE|Member, she has held residencies at Tanglewood Music Center, Spoleto Festival, and the Los Angeles Master Chorale. She is an artistic director of Shastra, promoting cross-cultural connections between the musical traditions of India and the West.

| First performance | September 18, 2021, Xian Zhang conducting the Seattle Symphony with oboist Mary Lynch VanderKolk |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 3 oboes, 3 clarinets, 3 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

Diaspora – Saxophone Concerto

Billy Childs

Born 1957, Los Angeles, California

Editor’s Note: The following program note contains excerpts adapted from original remarks by the composer.

Billy Childs describes this saxophone concerto as a “symphonic poem” which strives to chronicle the paradigm of the forced Black American diaspora, as sifted through the prism of his own experience as a Black man in America. Childs wrote the work for soloist Steven Banks, and the first thing the pair discussed was the narrative: What particular story would the piece tell? How would it unfold?

They decided that, in much the same way that Maurice Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit illustrates three poems by Aloysius Bertrand, so this concerto would illustrate poems by Black poets. Further inspiration came from the elegantly succinct and fluent structure of Samuel Barber’s First Symphony, which ties together a handful of thematic materials into the seamless and organic whole of a multi-sectioned suite.

The chosen poems—“Africa’s Lament” by Nayyirah Waheed, “If We Must Die” by Claude McKay, and “And Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou—inspired a three-part storyline: Motherland, If We Must Die, and And Still I Rise. Musically, various melodies and thematic motifs are treated in different ways (inverted, augmented, contrapuntally treated, reharmonized, etc.), in the manner of a loosely structured theme and variations, but with several themes.

I: Motherland. The first theme (introduced by the soprano saxophone then joined by an uplifting accompaniment from the orchestra) evokes the well-being and security of Africans in the motherland. It is understood, of course, that there were tribal wars, treachery, and misery—even slavery; Childs is not trying to illustrate a utopia. Rather, he depicts, as he describes it, “a sense of purity—a purity arising from having been thus far unobstructed by the outside destructive forces that would later determine our fate.”

The sax motif (accompanied by marimba and plucked cello) quickly modulates to remote tonalities, and a busy pattern in the strings creates a sense of foreboding. As the harmonies become more ominous, the sax plays urgent bursts of melodic fragments. A battle ensues—“a battle between the slave traders and the future slaves,” in Childs’ words— climaxing with the full orchestra bolstered by a brass fanfare. After a dissonant orchestral hit, the sax utters a melancholy theme as the enslaved people are led to the slave ship. The first solo cadenza reflects on the pain of being captured like a wild animal and led to a ship, and to a future hell.

II: If We Must Die. Part two of the journey begins with a vision of the slave ship (a loud blast from the orchestra). The alto saxophone plays the rapid 12-tone theme that was first heard during the battle between the African natives and the slave traders in the previous movement and that will weave in and out of the entire piece.

“The slaves are boarded onto the ships, and the middle passage journey to America begins; sweeping rapid scales in the lower strings, woodwinds, and harp describe the back-and-forth movement of the waves,” Childs says. “This section develops and reaches a high point with a jarring saxophone multiphonic pair of notes followed by a forearm piano cluster; we now see America for the first time, from the point of view of the slaves.” A push-and-pull exchange between sax and orchestra represents the confusion, rage, and terror of families ripped apart as humans are bought and sold like cattle.

A mournful lament of despair is brought on by the sheer brutality of this new slavery paradigm. The alto sax plays an inversion of the melancholy soprano sax theme from the end of the first movement. Meanwhile, a background pattern from vibraphone and celeste depicts a slow and steady growing anger.

The following section is marked by an interplay between the alto sax and the orchestra, describing resistance, anger, and rebellion against subhuman treatment over the course of centuries. After five orchestral stabs, the alto saxophone plays a short, tender cadenza signifying the resilience of Black Americans and introducing the idea of self-love, self- worth, and self-determination.

III: And Still I Rise. This movement is about Black empowerment. The church has always been a cultural focal point in the Black community, a sanctuary providing psychological and emotional relief from the hardships of Black life in America. It is also a place to worship, pray, and wrestle with larger spiritual and existential questions. Beyond (or perhaps because of) that, the church is historically the hub of Black political and cultural activism in America.

And so this final chapter of the piece begins with a hymn-like passage— a variation of the folk-like melody at the very beginning of the concerto. It is a plaintive reading for just alto saxophone and piano, as though the soloist were a singer during a Sunday church service. Soon the sax theme is given a lush, Romantic accompaniment, as a healing self-awareness and love becomes palpable. This is followed by a repeated march-like idea, symbolizing steely determination in the midst of formidable obstacles, as the sax plays rapidly above the orchestral momentum, until we reach the final victorious fanfare. Maya Angelou’s shining poem reminds us (and America) that Black people cannot and will not be held to a position of second-class citizenship—we will still rise.

Abridged from remarks by Billy Childs © 2023

About the composer

Billy Childs is one of the most distinctly American composers of his era, successfully marrying the musical products of his heritage with the Western neoclassical traditions of the 20th century in a powerful symbiosis of style, range, and dynamism. His jazz career began in 1977, and as a pianist he has performed with artists such as Yo-Yo Ma, Sting, Renee Fleming, and Chick Corea. He has been commissioned by America’s leading orchestral and chamber organizations, including Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Leonard Slatkin and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, the Kronos Quartet, and Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra, and his works have been heard at Carnegie Hall and Disney Concert Hall. He has also garnered 17 Grammy nominations and six awards, including two for Best Instrumental Composition, as well as Chamber Music America awards for New Jazz Works and Classical Commissioning (making him the first artist to receive awards in both genres). He was a Guggenheim Fellow in 2009, and in 2015 he received a Composers Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

| First performance | February 10, 2023, the Kansas City Symphony conducted by Ruth Reinhardt with soloist Steven Banks |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | solo saxophone (soprano and alto); 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo and alto flute), oboe, English horn, 2 clarinets, bassoon, contrabassoon, 3 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, percussion, harp, piano (doubling celeste), strings |

| Approximate duration | 23 minutes |

Fifth Symphony

Sergei Prokofiev

Born 1891, Sontsovka, Ukraine

Died 1953, Moscow, Russia

In the summer of 1944, Prokofiev was working on his Fifth Symphony at the Soviet Composers’ Retreat in Ivanovo, far outside Moscow, where he had been evacuated to safety from the war. On the other side of Europe, Allied troops were landing on the Normandy beaches, beginning the liberation of France. The following winter, when the symphony premiered on January 13, 1945, Soviet troops were starting their final advance into German-held territory. Two weeks later, they would liberate Auschwitz. In the spring, they would reach Berlin, and soon the Western and Eastern Fronts would meet, sealing victory in Europe.

Unlike so much wartime music that reflects overwhelming horror and suffering, Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony is filled with warmth and measured optimism. It seems to acknowledge the heaviness of the war while looking ahead to the future and recognizing what was worth fighting for. “I conceived of it as glorifying the grandeur of the human spirit,” Prokofiev said, “praising the free and happy man—his strength, his generosity, and the purity of his soul.”

The night the symphony premiered in Moscow, the intermission was followed by an artillery salute to the soldiers of the First Ukrainian front, who had broken through German defenses hundreds of miles to the west. As the first distant volley shook the hall, Time magazine later reported, “A lank, bald-headed man in white tie and tails […] mounted the podium and stood with bowed head, facing the Moscow State Philharmonic. He seemed to be counting off the rumbles of artillery. At the 20th, he raised his baton and began the world’s premiere of his newest symphony. The bald-headed conductor was Russia’s greatest living musician, Sergei Prokofiev.”

Pianist Sviatoslav Richter recalled: “When Prokofiev stood up, the light seemed to pour straight down on him from somewhere up above. He stood like a monument on a pedestal. And then, when Prokofiev had taken his place on the podium and silence reigned in the hall, artillery salvos suddenly thundered forth. His baton was raised. He waited, and began only after the cannons had stopped. There was something very significant in this, something symbolic. It was as if all of us—including Prokofiev—had reached some kind of shared turning point.”

The following November, after the end of hostilities in both Europe and the Pacific, the Fifth Symphony received its US premiere with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Serge Koussevitzky. It was a tremendous success that put Prokofiev on the cover of Time. The symphony was “large in scale,” wrote the Time reporter, “a great, brassy creation with some of the intricate efficiency and dynamic energy of a Soviet power plant and some of the pastoral lyricism of a Chekhov countryside.” Koussevitzky ecstatically called it “The greatest [musical event] since Brahms and Tchaikovsky! It is magnificent! It is yesterday, it is today, it is tomorrow …”

The enormous scale is evident from the lushly orchestrated first movement. The opening Andante glows, working its way up from its principal woodwind themes (flute and bassoon, then oboes and flutes) to a climax of tam-tam crashes. The second movement, Allegro marcato, is more sprightly, beginning almost like chamber music before gaining velocity through propulsive, motoric rhythms that recall Prokofiev’s pre- Soviet style of the 1920s. It cuts off abruptly, as if to say, “that’s enough.”

The third movement, a lyrical Adagio, is reminiscent of Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata in its lilting, nocturnal backdrop. Contrasting ideas intervene, but when the “Moonlight” accompaniment returns, it has become horrible and overwhelming. Finally, it fades and moves on, dream-like. The finale (Allegro giocoso) begins with the cellos and basses contemplating a return of the first movement’s main melody. But then the tempo picks up and starts to shake off enormous tension—a celebration for people who had not had one for a long time.

Adapted from a note by Benjamin Pesetsky © 2022

| First performance | January 13, 1945, in Moscow, the composer conducting the USSR State Symphony Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | November 1, 1946, Vladimir Golschmann conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 23, 2022, Kirill Karabits conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 46 minutes |

Artists

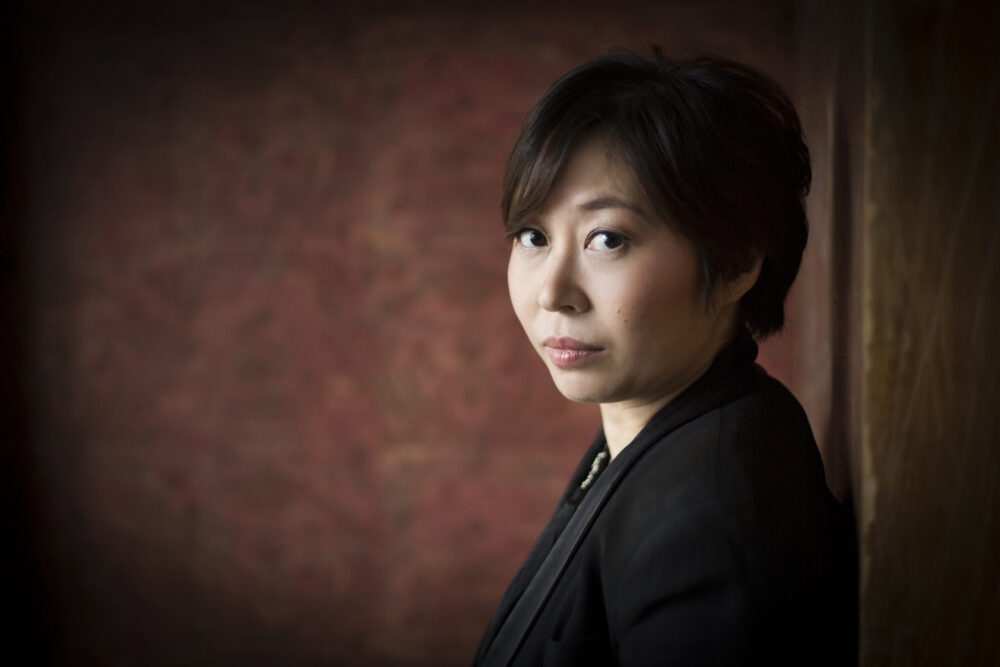

Xian Zhang

Xian Zhang is in her tenth season as Music Director of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. Under her leadership, the NJSO won two awards at the 2022 mid-Atlantic Emmys for their concert films, including Emerge. This season she also becomes Music Director of the Seattle Symphony and continues with the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano as Conductor Emeritus following her tenure as Music Director (2009–16). She also appears regularly with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and Philadelphia Orchestra. Her 2022 recording with the latter, Letters for the Future, won Grammy awards for Best Contemporary Classical Composition (Contact by Kevin Puts) and Best Classical Instrumental Solo.

In addition to the SLSO, this season she returns to the Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, National Arts Centre Ottawa, and the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. She also makes her Finnish National Opera debut in Tosca, which she recently conducted at the Metropolitan Opera following her house debut with Madama Butterfly. Recent highlights include subscription concerts with the Boston, London, Baltimore, and Montreal symphony orchestras, Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo, Houston Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, National Symphony Orchestra, and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s.

Xian Zhang previously served as Principal Guest Conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and BBC National Orchestra and Chorus of Wales, the first female conductor to hold a titled role with a BBC orchestra. In 2002, she won the Maazel-Vilar Conductor’s Competition and was appointed the New York Philharmonic’s Assistant Conductor, subsequently becoming Associate Conductor and first holder of the Arturo Toscanini Chair.

Steven Banks

The saxophone’s “best friend, fiercest advocate and primary virtuoso in the classical realm” (Washington Post), Steven Banks strives to bring his instrument to the heart of the classical world, commissioning and composing music that expands the saxophone repertoire. Diaspora, commissioned by Young Concert Artists and ten orchestras—the largest consortium ever for a saxophone work—marks a major milestone in his mission. His growing list of premieres includes Carlos Simon’s hear them, Augusta Read Thomas’ Haemosu’s Celestial Chariot Ride, and Christopher Theofanidis’s Visions of the Hereafter. This season, he premieres Joan Tower’s Love Returns at the Colorado Music Festival.

In addition to the SLSO, this season he makes debuts with the Indianapolis, Oregon, and Montreal symphony orchestras, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, and BBC National Orchestra of Wales. Recent highlights include the Cleveland and Minnesota orchestras, Seattle Symphony, Pittsburgh and Boston symphony orchestras, New World Symphony, Aspen Festival Orchestra, and the orchestras of Cincinnati, Utah, San Diego, and Detroit.

His own compositions are increasingly in demand and he has been commissioned by Young Concert Artists and the chamber music festivals of Tulsa, Tucson, Bridgehampton, and Chamber Music Northwest, as well as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Through My Mother’s Eyes for Hilary Hahn), and his saxophone and piano works, including Come As You Are, are among the most performed by saxophonists worldwide.

A longstanding supporter of diverse voices in classical music, this season he launches Come As You Are—a community engagement project in partnership with orchestras, designed to increase representation in the concert hall. Steven Banks is proud to be the first saxophonist to receive an Avery Fisher Career Grant and win First Prize at the Young Concert Artists Susan Wadsworth International Auditions.