Shostakovich’s 15th (December 5-6, 2025)

Program

December 5-6, 2025

- John Storgårds, conductor

- Kian Soltani, cello

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

- Three Romances for orchestra (after Three Romances for violin and piano, Op. 22)

- I. Andante molto

- II. Allegretto

- III. Leidenschaftlich schnell (Passionately fast)

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

- Cello Concerto in C major, Hob. VIIb:1

- Moderato

- Adagio

- Finale (Allegretto molto)

Kian Soltani, cello

Intermission

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

- Symphony No. 15 in A major, Op. 141

- Allegretto

- Adagio –

- Allegretto

- Adagio – Allegretto

Rebellion and Reckoning

The first act of rebellion in this concert is a quiet one. It belongs to the backstory of the music, a set of Romances originally composed for violin and piano. When Clara Wieck’s ambitious and controlling father refused to consent to her marriage to Robert Schumann, the couple took him to court. The determination this 20-year-old woman had poured into her music-making emerged in her personal life, and it would shape her career as one of 19th-century Europe’s most influential concert pianists. But the marriage she and Robert had fought for ate into the creative space needed for composing, and only two major works with orchestra survive. The remainder of her compositions were chamber works, piano pieces, and songs.

Benjamin de Murashkin’s orchestration of Clara Schumann’s opus 22 Romances seeks to remedy the situation. He describes it as one of the most difficult things he’s ever had to orchestrate, because of the swiftly flowing broken chords in the piano part. His solution was to focus on the individual elements—melodies, harmonies, gestures, and textures. The result, he says, “is hopefully something that sounds like it was always ‘meant to be’ rather than orchestrated piano music.”

Murashkin downplays the idiomatic aspects of his source material. Joseph Haydn’s C-major concerto does the opposite: playing to the strengths of the cello and exploiting the latest (for 1760) in virtuoso techniques. The result is exhilarating—no wonder cellists and music lovers were so excited when this long-lost concerto turned up in a Prague library in the 1960s.

Shostakovich returns the program to the theme of (quiet) rebellion and determination. He survived a turbulent and dangerous period of history to become the 20th century’s most important, and most enigmatic, symphonist. Like many of his works, his final symphony, the Fifteenth, includes musical quotations, ironic sub-texts, and in-jokes. It begins in a “toyshop”—lighthearted, even cheeky—but the clouds soon gather, and in the final reckoning this symphony is full of ambiguities and equal parts optimism and pessimism.

Three Romances for orchestra

Clara Schumann

Born 1819, Leipzig, Germany

Died 1896, Frankfurt, Germany

The composer Clara Schumann lived for music, for its power to “clothe one’s feelings in sound.” She was as romantic as they come, believing from a young age that love and music were one and the same, and so aptly called her signature pieces “romances”—of which she wrote over a dozen. Most were composed with love for her husband, Robert. In this opus, you may intuit the coda of his most famous song, Widmung, a wedding gift to Clara, in the harmony at the end of the third romance. Her romances were influenced by the Songs Without Words of her mentor Felix Mendelssohn and influenced the intermezzos of the younger composer she mentored, Johannes Brahms, who knew her romances well.

Composed as duets for solo violin and piano, the opus 22 Romances were inspired by the prominent 19th-century violinist, Joseph Joachim, for whom Brahms also composed his violin concerto. Schumann admired Joachim’s “depth of poetic feeling,” how he played with “his whole soul in every note.” Most famous for their rendering of Beethoven’s violin sonatas, the duo gave countless concerts together for decades, from London to Vienna. They performed these sweeping romances on at least six occasions, plus private performances for Robert Schumann, Brahms, and the King of Hanover.

Never a composer to define her works by specific titles, Schumann distinguishes each exquisite romance only by key and tempo. The first is an improvisatory Andante molto in D-flat major, overflowing with tenuous longing (sehnsucht). The second, an Allegretto in heart-breaking G minor, is marked “mit zartem vortrage” (with gentle tenderness). The last is an ecstatic B-flat major labelled merely “Leidenschaftlich schnell” (passionately fast). “There is nothing which surpasses the joy of creation,” Schumann wrote during the summer of 1853, when shecomposed opus 22, “if only because through it one wins hours of self- forgetfulness, when one lives entirely in a world of sound.”

(Pastel drawing by Adolph von Menzel, 1854)

In recent decades, many have orchestrated Schumann’s works, for good reason. Though her Piano Concerto in A minor is her only surviving orchestrated work, as a 13-year-old prodigy she had studied orchestration. Thus she conceived her music orchestrally, rich in layered harmonies and countermelodies with few virtuosic flourishes, which translates well for orchestra. Composer Benjamin de Murashkin passes the violin’s melody between the orchestra’s winds and violins, while the brass and low strings take on the piano part, capturing the intimate spirit of these touching romances. You are in for a special treat; no recording yet exists of Schumann’s historically important opus 22 played by an orchestra.

Sarah Fritz © 2025

Sarah Fritz is the author of the forthcoming biography of Clara Schumann,

Madame Composer (2026).

| First performances | November 12, 2021, John Storgårds conducting the Copenhagen Philharmonic |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, oboe, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, strings |

| Approximate duration | 11 minutes |

Cello Concerto in C major

Joseph Haydn

Born 1732, Rohrau, Austria

Died 1809, Vienna, Austria

For more than 150 years following Haydn’s death, there was just one Haydn Cello Concerto: the D major concerto of 1783. Although its music survived in Haydn’s own writing, there were queries about the authorship, partly because Haydn had not entered a cello concerto in this key in the thematic catalog of his works. He had entered the beginning of a cello concerto in C major, but of that work no trace was to be found. Then, in 1961, it was noticed that a set of parts for a cello concerto, held in the Prague National Museum, had the same beginning as Haydn’s catalog entry.

This discovery caused great excitement, not just because there are so few cello concertos, especially from the 18th century, but because of the high quality and attractiveness of the music, and the 20th-century premiere of the concerto took place in the city where it was discovered, as part of the Prague Spring Festival, in 1962.

The C major concerto was probably composed in the early 1760s, during Haydn’s first few years of service for the Esterházy princes, and was most likely played by Joseph Weigl, a brilliant cellist in Haydn’s orchestra at Eisenstadt between 1761 and 1769, and a composer himself. (The Prague library collection also included a concerto by Weigl in the hand of the same 18th-century copyist who’d made the Haydn parts.) Weigl had evidently expanded Haydn’s awareness of what the cello can do, and Haydn had included several remarkable solos for his colleague in his early symphonies.

The style and form in the C major concerto display aspects of the Italian baroque concerto—solo passages alternating with ritornello passages in which the main themes “return.” But the harmonic structure is closer to Classical sonata form, in the new style that Haydn himself was forging. The long phrases give a sense of continuity, especially when the soloist is leading the discourse.

Thumbs Up

Joseph Weigl (1766–1846) was one of the earliest exponents of a new virtuoso cello technique: by placing his left thumb on the fingerboard he could maneuver up and down on one string at unprecedented speed. He almost certainly introduced the idea to Haydn, because without that technique the spirited finale of the C major concerto would be impossible to play.

In this concerto, Haydn is writing for his soloist and his public, rather than making a take-it-or-leave-it personal statement. This is true also of the elegant and graceful slow movement, featuring just the soloist and the strings. Haydn leaves the best till last, in the dynamic finale’s almost non-stop virtuoso fireworks.

David Garrett © 2011

| First performance | The 20th-century premiere took place on May 19, 1962, with Charles Mackerras conducting the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra and Miloš Sádlo as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | April 3, 1969, conducted by Walter Susskind with soloist Mstislav Rostropovich |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 19, 2013, conducted by David Robertson with Yo-Yo Ma as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo cello; 2 oboes, 2 horns, strings |

| Approximate duration | 25 minutes |

Symphony No. 15

Dmitri Shostakovich

Born 1906, St. Petersburg, Russia

Died 1975, Moscow, USSR

Setting the Scene

Dmitri Shostakovich began his final symphony in a hospital bed in 1971. The Symphony No. 15 would be premiered in Moscow, conducted by his son Maxim, in 1972. By 1975 the great composer would be dead, leaving behind the enigma of his life and work.

You can hear in this last symphony a sampling of influential motifs from the composer’s past—from the William Tell Overture; from Richard Wagner’s operas Die Walküre, Götterdämmerung, and Tristan und Isolde; and from Shostakovich’s own works, especially his Symphony No. 11 (The Year 1905) and No. 7 (Leningrad). Shostakovich also uses his own personal motto, which appears in many of his works—the “DSCH” theme that refers to his name. (“DSCH” uses the German transliteration of his name—Dmitri SCHostakowitsch—with the German names for musical notes, which include Es for E-flat and H for B-natural: so DSCH = D–E-flat–C–B.) This motto is his proclamation from the mass of brutalized humanity: “I am here.”

POV – Discovering the 15th Symphony

Shostakovich’s last symphony is a fitting coda to an important body of symphonic work—more substantial than that of any other major composer of the past 200 years. Following a pair of expansive song symphonies, it reverts to purely instrumental music; the orchestra it uses is not even especially large, apart from a sizeable percussion section, and it is deployed judiciously. The tone of the piece seems, apart from its opening movement, mostly restrained and contemplative. A number of listeners, including some who knew the composer, find in this music a tone of valediction, even a meditation on mortality.

That interpretation, however, has been made in hindsight: this work was Shostakovich’s last symphony and he had not long to live. And details of Shostakovich’s biography don’t neatly support this view of the symphony. It’s true the composer had been in poor health for some time when he began working on the piece. In the mid-1960s he’d developed a heart ailment, which sapped his energy, and shortly thereafter began to suffer from poliomyelitis, which made walking and even writing difficult. But in 1970, a regimen of physical therapy and medication greatly relieved his symptoms, and he grew encouraged about his capacity for work. It was in this hopeful frame of mind that he wrote the 15th Symphony in the spring and summer of 1971.

Accordingly, some commentators have detected a playful tone in this composition, especially the first movement. Shostakovich never confirmed either the morbid or the more cheerful interpretation of his last symphony. Indeed, he barely commented on it at all, and what he did say hardly tipped the scales in favor of one or the other of these outlooks. For example, he said the music of the first movement, with its antic quotation of the galloping theme from Gioachino Rossini’s William Tell Overture, was like a “toy shop.” In fact, the music seems to support each view in turn, which seems only right. This is a complex, apparently ambiguous, work of art created by a complex and apparently ambiguous artist. In it, irony, elegy, drama, and much else seem to find expression, and it serves neither the music nor ourselves to try to typecast it as one thing only.

Listening Guide

Shostakovich begins the first movement (Allegretto) with bright, ethereal sounds of bells and flutes. The flute holds the spotlight for the first several pages of the score before handing off its capricious melody to a bassoon. That melody gradually develops into an ironic march, a type of music Shostakovich wrote often over the course of his career. Suddenly, the brass interject the gallop from the William Tell Overture, a figure that will recur four more times before the movement is done. What is this doing here? Shostakovich explained it only as one of the “toys” in the “shop.” The music develops in unforeseen ways. It grows vehement; it dissolves into cross-rhythms—superimposed patterns of five, six, and eight notes per measure; it reaches a ringing climax, replete with majestic chords in the brass; it reduces to solo passages for violin, xylophone, and other instruments. In short, from its modest opening, it traverses remarkably wide terrain.

Beginning with a juxtaposition of somber brass chords and wide- stepping phrases for solo cello, the slow second movement (Adagio) is entirely different. Here, nearly everything is set in contrasting monochromatic sonorities, as Shostakovich writes for choirs of brass or 28 woodwinds or strings, or else uses single instruments. Sustained tones from the bassoons provide a bridge to the third movement (Allegretto), a brief scherzo whose use of solo violin recalls the same practice in the scherzo of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Towards the end of this movement, Shostakovich presents his signature “DSCH” motto (listen for the horns).

The finale uses another extraneous quotation, this one from Wagner. This is a three-note motif associated with fate in that composer’s four- opera Ring cycle, and it sounds at the very outset of the symphony’s concluding movement. Twice more, between spare percussive textures, the motif sounds. And then, the music slips into a blithe melody for the violins, the transition being all the more surprising for how smoothly it is accomplished. Yet the Wagnerian “fate” motif has not been banished and the clear complexion of the new melody darkens as it metamorphoses into more complex modes of expression. The music becomes wistful, ghostly, threatening by turns, and it eventually attains a disturbing climax. Shostakovich gives the final word to the percussion. It’s as if he’s returned to his toy shop to watch the last movements of some mechanical doll before it winds down.

Adapted from notes by Eddie Silva © 2017 (Setting the Scene) and Paul Schiavo © 2004

| First performance | January 8, 1972, Moscow, Maxim Shostakovich conducting the All-Union Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | August 11, 1973, Leonard Slatkin conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | January 21, 2017, Andrey Boreyko conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, a large percussion section, celeste, strings |

| Approximate duration | 45 minutes |

Artists

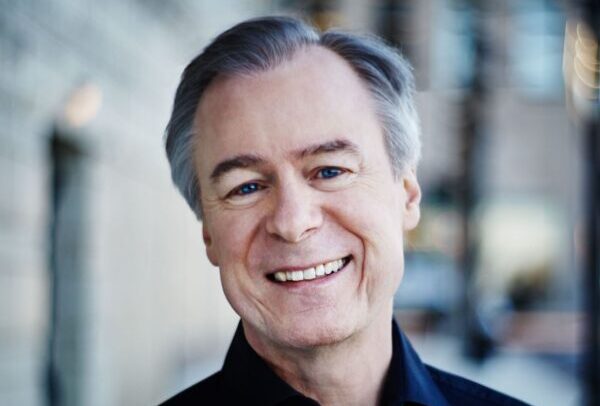

John Storgårds

Conductor and violinist John Storgårds is widely recognized for his creative programming flair as well as his rousing yet refined performances. He is Chief Conductor of the BBC and Turku philharmonic orchestras and has earned acclaim as the longstanding Artistic Director of the Lapland Chamber Orchestra. Currently Principal Guest Conductor of the National Arts Centre Orchestra Ottawa, he will take up the role of Music Director in 2026.

Storgårds has been a frequent guest with the SLSO since 2012. He also conducts the Berlin Philharmonic and other leading European orchestras; the BBC Symphony and London Philharmonic orchestras; and major orchestras in Australia and Japan. In the US he has conducted the Boston, Chicago and Detroit symphony orchestras, New York Philharmonic, and the Cleveland Orchestra.

Highlights of the 2025/26 season have already included appearances at the BBC Proms with the BBC Philharmonic and Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk with English National Opera. He recently conducted the BBC Philharmonic at the Beijing Music Festival, and in January will make his San Francisco Symphony debut.

His repertoire includes the symphonies of Sibelius, Nielsen, Bruckner, Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann. He also regularly performs premieres and many new works are dedicated to him. His discography includes Sibelius and Nielsen symphony cycles, and music by George Antheil, and he is recording Shostakovich symphonies with the BBC Philharmonic.

John Storgårds studied violin with Chaim Taub and was concertmaster of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Esa-Pekka Salonen, before studying conducting with Jorma Panula and Eri Klas.

Kian Soltani

Born in Bregenz, Austria, to a family of Persian musicians, Kian Soltani joined Ivan Monighetti’s class at the Basel Music Academy aged 12. A recipient of the Anne-Sophie Mutter Foundation scholarship in 2014, he studied at the Kronberg Academy in Germany and International Music Academy in Liechtenstein. He now appears regularly with many of the world’s leading orchestras and conductors and as a guest in prominent festivals, establishing himself as a leading voice among today’s generation of cellists. This is his SLSO debut.

Highlights of the 2025/26 season include: a performance with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and Gianandrea Noseda at the Hamburg Elbphilharmonie; a return to the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France under Daniel Harding; and debuts with the Orchestre National de France and the Sydney, New Zealand, and Atlanta symphony orchestras. Soltani will also tour Europe with the WDR Sinfonieorchester and Cristian Măcelaru, and with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra and Eva Ollikainen. As a recitalist, he will tour Europe with violinist Renaud Capuçon and pianist Mao Fujita, and with pianist Benjamin Grosvenor, while joining clarinetist Andreas Ottensamer and pianist Alessio Bax for performances in the United States.

In 2018 he released his acclaimed debut album Home, featuring music by Schubert, Schumann, and Reza Vali. This was followed by Dvořák’s Cello Concerto (Staatskapelle Berlin and Daniel Barenboim) and a Schumann album featuring the cello concerto and Lieder transcriptions (Camerata Salzburg). His 2021 solo album Cello Unlimited won the Innovative Listening Experience Award at the 2022 Opus Klassik Awards. Kian Soltani plays “The London, ex-Boccherini” Antonio Stradivari cello, kindly loaned to him by a generous sponsor through the Beares International Violin Society.