SLSO at the University of Missouri (January 28, 2026)

Program

January 28, 2026

- Samuel Hollister, conductor

- Celeste Golden Andrews, violin

Dag Wirén (1905-1986)

- Concert Overture No. 1, Op. 2

Ralph Vaughan Williams 1872-1958)

- The Lark Ascending

Celeste Golden Andrews, violin

Intermission

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

- Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43

- Allegretto

- Tempo Andante, ma rubato

- Vivacissimo – Lento e suave –

- Finale (Allegro moderato)

Concert Overture No. 1

Dag Wirén

Born 1905, Striberg, near Nora, Sweden

Died 1986, Danderyd, Sweden

Swedish composer Dag Wirén held his own work to exacting standards, but the young Wirén clearly had confidence that he had hit the mark with his Concert Oveture No. 1. Written in 1931, when the composer was just 26 years old, the overture is only the second piece for which Wirén sought publication and performance.

Wirén’s music responded to several Swedish composers of an earlier era as well as contemporaries including Wilhelm Stenhammar and Kurt Atterberg. He was also inspired by the great Nordic composers of the 19th and early 20th centuries, none more so than Jean Sibelius. Wirén considered Sibelius the greatest of all Nordic composers, and the Finnish composer’s influence gives us a through line from Wirén’s Concert Overture No. 1 to the final work on tonight’s program, Sibelius’ own Symphony No. 2.

Despite using characteristically colorful and adventurous harmony in the vein of Sibelius and other modernist Nordic composers, the overture (like much of Wirén’s work) is structured in a very traditional sonata form. The urgent main theme of Wirén’s overture and a peaceful, pastoral second theme are unified triumphantly by the end of the work.

That tried-and-true approach to structure dovetailed with Wirén’s desire to write listener-friendly, accessible “modern” music. Across his career, that impulse yielded a diverse output, which ranged from concert compositions, including symphonies, concertos, and ballets, to popular music, including film scores and even Sweden’s 1965 Eurovision Song Contest entry, “Absent Friend.”

Swedish orchestral music is still somewhat overshadowed by that of other Nordic countries, what with the success of Sibelius in Finland and Edvard Grieg in Norway. Yet Swedish orchestral music from the romantic and modern eras remains an exciting domain for discoveries of hidden gems. The music of Wirén is a wonderful case in point.

Adapted from notes by Samuel Hollister.

| First performance | April 2, 1932, at the inauguration of Örebro Concert Hall in Örebro, Sweden |

| First SLSO performance | This concert |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

The Lark Ascending

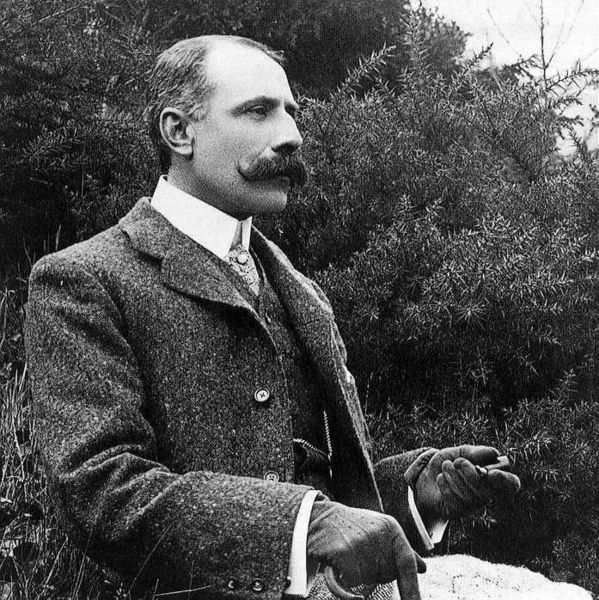

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Born 1872, Down Ampney, England

Died 1958, London

The day that England entered World War I, Ralph Vaughan Williams was vacationing on the coast of Margate, in Kent. Contrary to his second wife Ursula’s account some 50 years later, he was not watching troops embark for France when he began The Lark Ascending. In fact, as he strolled the cliffs near his seaside resort, his mind mostly on melodies, he may not have realized exactly what he was witnessing: ships engaged in fleet exercises. A tune popped into his head, and he pulled out a notebook to jot it down. A boy saw him, assumed that he was a spy scribbling code for the enemy, and reported him to a police officer, who arrested and briefly detained him.

Later in 1914, Vaughan Williams enlisted in the army, despite being 41 years old. He put aside the score for The Lark Ascending while he served as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps. After years bearing stretchers in France and Greece, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. The incessant gunfire damaged his hearing and contributed to the severe deafness that he suffered in his old age, but most of his injuries were emotional. As with Elgar and so many others, World War I left him deeply disillusioned. The horrific carnage that he witnessed on the front and the devastation of his native country made him nostalgic for the bucolic landscapes of the past. In 1919 he returned to The Lark Ascending.

Originally written for violin and piano and later scored for orchestra, the work was inspired by George Meredith’s poem of the same name. Vaughan Williams copied ten nonconsecutive lines from it on the flyleaf of his score. Like Meredith, who was buried in the town cemetery, Vaughan Williams spent most of his life in the then-rural village of Dorking, Surrey, and had many real-life opportunities to hear the lark’s “silver chain of sound.” A triumph of mimesis, the pentatonic trills and flourishes of the solo violin suggest both the bird’s song and its flight over the English landscape. A gradual change in tempo hints at bygone village festivals, but the music is too free and rhapsodic to be strictly programmatic. After its first orchestral performance in June of 1921, a critic from The Times wrote admiringly, “It showed serene disregard for the fashions of today or yesterday. It dreamed itself along.”

In 2014, a U.K. radio station announced that The Lark Ascending was Britain’s favorite classical work, but its popularity is not limited to its country of origin. In 2011, when New Yorkers were asked to select music for the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, The Lark Ascending came in second. The real problem with familiarity is not that it breeds contempt. Contempt, after all, requires attention. Familiarity kills when we stop experiencing fine and beautiful things as they are, in the holy moment, and turn instead to dead metaphors and pat explanations. In that explicative thicket, it’s hard to discern one smallish, brownish bird of a species that few of us see anymore. But like The Lark Ascending, it is fine and beautiful. Stop making it stand for things, and let it soar away.

| First performance | June 14, 1921, Marie Hall as soloist, with Adrian Boult conducting the premiere of the orchestral version at Shirehampton Public Hall |

| First SLSO performance | October 3, 2008, Heidi Harris as soloist with David Robertson conducting a “Classical Detours” English-themed concert |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 8, 2019, David Halen as soloist with Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, oboe, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, triangle, strings |

| Approximate duration | 13 minutes |

Symphony No. 2

Jean Sibelius

Born 1865, Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

Changing musical tastes and perspectives can drastically affect the reputations of many musicians. Composers once held in high regard can fall into relative neglect, while others rise from comparative obscurity to respect and popularity. Among 20th-century composers, Jean Sibelius has, to some extent, done both. During his lifetime, Finland’s great symphonist enjoyed international acclaim amounting to adulation in certain quarters. During the 1920s and 1930s, some conservative musicians, bewildered by the compositions of Stravinsky and other advanced musical thinkers, even compared Sibelius to Beethoven and pointed to his work as the future of music. But following the composer’s death, in 1957, his star was partially eclipsed by the growing appreciation of the great modernist composers of the early 20th century, and the frequency with which his works were performed fell sharply.

Today, however, it is possible to view Sibelius in a more objective light, and the past four decades have seen a significant revival of interest in his music: new recorded cycles of the complete symphonies; increasingly frequent performances of his works by leading artists and orchestras; and praise from a new generation of composers. Many of the latter are symphonists representing the emergence of what has been labeled “the New Romanticism,” but Sibelius has also found admirers in the avant-garde. The late Morton Feldman, a composer of delicate, abstract music, publicly proclaimed his affection for the Finnish composer’s work. Another American composer, the post- minimalist John Adams, often programs and conducts Sibelius’s music together with his own compositions.

Sibelius’s ultimate place in the history of music will surely be as neither the savior his partisans hailed nor the reactionary formerly derided by his detractors. Rather, he may best be understood as a 19th-century composer whose hearty constitution allowed him to live and work well into the 20th. Instead of adopting the innovations of the modernist revolution, Sibelius remained true to his musical background, continuing to use the rich tonal language of the late-Romantic era to create a powerful and personal body of music.

Sibelius’s Second Symphony can serve to dispel two other misconceptions surrounding his work. Because the moods his compositions present often seem intensely subjective, a casual listener might easily assume their creation was guided by expressive rather than formal considerations. In fact, Sibelius achieved a remarkable mastery of tonal architecture. The Second Symphony reveals a four-movement structure in the classical mold: a strong opening of conventional design followed by a slow movement, scherzo, and triumphant finale. The conciseness of the work’s themes and their recurrence in succeeding movements provide further evidence of a concern for formal coherence.

Then there is the notion that Sibelius was a nationalist composer whose music consistently reflected the rugged landscapes, spirited people, and even the mythology and folk legends of his native Finland. Sibelius certainly drew inspiration from these sources at times, but he disavowed any extra-musical meaning, Finnish or otherwise, in his symphonic work. “My symphonies are music conceived and worked out in terms of music and with no literary basis,” he declared in an interview. He was particularly irritated by attempts to explain his Second Symphony in terms of a patriotic scenario. We can note, moreover, that he composed this work not by some Nordic fjord but, for the most part, during a visit to Italy during the early months of 1901.

The symphony opens with eight measures of throbbing chords. These function as a motivic thread binding the first movement: they accompany both the pastoral first theme, announced by the oboes and clarinets (and echoed by the horns), and a contrasting second theme consisting of a sustained high note followed by a sudden descent. The latter merits careful attention, since it will appear in several transformations later in the work.

A drum roll announces the second movement. Sibelius sketched the initial theme for this part of the symphony while considering writing a tone poem on the Don Juan legend, and much of the music that follows has an intensely dramatic character that seems suited to that story. Some of the most stirring moments involve variations of the second theme of the preceding movement.

Distant echoes of the series of chords that opened the symphony can be heard throughout the scherzo that constitutes the third movement: in the repeated notes that start both the violin runs at the beginning of the movement and the limpid oboe melody later on, as well as in the trombone chords that punctuate the heroic theme that appears near the movement’s end. This latter passage leads without pause into the last movement, which begins modestly but builds to one of the most exultant finales in the symphonic literature.

Adapted from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2014

| First performance | March 8, 1902, the composer conducting the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | November 8, 1910, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | January 29, 2023, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 46 minutes |

Artists

Samuel Hollister

Assistant Conductor and The Fred M. Saigh Youth Orchestra Music Director

Samuel Hollister is a dynamic conductor, pianist, harpsichordist, and composer who believes in the power of music to build community and tell meaningful stories. He serves as the Assistant Conductor of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and The Fred M. Saigh Youth Orchestra Music Director. He completed his residency in orchestral conducting at the Yale School of Music in 2024, has previously led the Civic Orchestra of New Haven, and has also taught at the University of Rhode Island as Director of Orchestral Activities.

Hollister is a fierce advocate for new music and has collaborated with composers such as John Corigliano, Joan Tower, and Adolphus Hailstork. His initiatives have included commissioning new concertos for guitar and marimba and co-founding the Emilie Mayer Project, which published the first public domain edition of Mayer’s Overture No. 3. Through his nonprofit, Aurora Collaborative, he has championed innovative concert experiences and the blending of music with visual art and writing.

As a composer, Hollister has written for piano, chamber ensembles, orchestra, and choir, while his work as a pianist, harpsichordist, and vocal coach includes positions with Opera Saratoga and Peabody’s Opera Department. He has performed and conducted internationally, with appearances in South Africa, Spain, Mexico, Hungary, Austria, Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Canada, and he has participated in masterclasses with such notable figures as Yo-Yo Ma and Jeffrey Kahane.

In addition to his musical endeavors, Hollister enjoys chess and exploring nature with his camera.

Celeste Golden Andrews

Second Associate Concertmaster

Celeste Golden Andrews joined the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra as Second Associate Concertmaster at the start of the 2011-12 season. She began her musical studies at the age of three. When she was nine years old, she became a student of Arkady Fomin, violinist in the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and at 15, Andrews was accepted into the Curtis Institute of Music, studying with Jaime Laredo and Ida Kavafian. She completed her Bachelor of Music degree at Curtis in 2005, and in 2007, she received a Master of Music degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music where she studied with David Cerone and Paul Kantor.

Andrews is a laureate of several national and international competitions. Most notably, she was the Bronze Medalist at the International Violin Competition of Indianapolis in 2006. She has appeared as soloist with numerous symphony orchestras around the world, including the Latvian Chamber Orchestra in Riga, Latvia, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. As a chamber musician, she has appeared in series and festivals such as the Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players, the Festival de San Miguel de Allende, the Chamber Music Festival of Lexington, the Innsbrook Institute Music Festival, the Aspen Music Festival and School, and the Marlboro Music Festival. Andrews won a three-year fellowship to the Aspen Music Festival and School in 2004, and was subsequently awarded the Dorothy DeLay Memorial Fellowship by the festival, an award given to only one violin student each summer.

Andrews was the concertmaster of the New York String Orchestra Seminar in 2005 with concerts at Carnegie Hall. She also performed as concertmaster for the Orchestra of St. Luke’s in the New York City premiere of John Adams’ opera A Flowering Tree at Lincoln Center in 2009. She was a member of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra from 2010–11, and currently performs regularly with the IRIS Orchestra in Germantown, Tennessee. Andrews made her SLSO solo debut performing Camille Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso in November 2011.