Tchaikovsky’s Fourth (January 24-25, 2026)

Program

January 24-25, 2026

- Dima Slobodeniouk, conductor

- Wu Wei, sheng

Lotta Wennäkoski (b. 1970)

- Flounce

Jukka Tiensuu (b. 1948)

- Teoton – Concerto for sheng and orchestra

- Fever –

- Adrift –

- Game –

- Bliss

Wu Wei, sheng

Intermission

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

- Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

- Andante sostenuto – Moderato con anima – Moderato assai, quasi andante – Allegro vivo

- Andantino in modo di canzona

- Scherzo. Pizzicato ostinato (Allegro)

- Finale (Allegro con fuoco)

Flounce

Lotta Wennäkoski

Born 1970, Helsinki, Finland

Lotta Wennäkoski was born in Helsinki, Finland, in 1970 and studied violin, music theory, and Hungarian folk music at the Béla Bartók Conservatory in Budapest before continuing her studies at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, where her teachers included Eero Hämeenniemi and Kaija Saariaho, and in the Netherlands with Louis Andriessen. She has since composed in a variety of styles and settings: in addition to more conventional orchestral works such as Flounce, her output includes Jong, a piece for chamber orchestra with a juggler as soloist, a score for a silent film, and Lelele, her 2010 monologue opera about forced prostitution.

Flounce is one of Wennäkoski’s most frequently performed works, with more than 50 performances worldwide, and since the SLSO gave the US premiere in 2018, she has enjoyed increasingly prestigious international commissions. These include the chamber work Hele for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Prosoidia for violinist Ilya Gringolts and the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and Vents et lyres, a recorder concerto for Lucie Horsch and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

Wennäkoski is drawn to abstract concepts like buoyancy and fluidity rather than definite narratives; she tries to communicate textures and sensations through sounds as if they were words. She stated in an interview with Karoliina Vesa, “My music does not concretely describe anything; it is more about topics and moods.” Wennäkoski’s interest in words and poetry defies the stereotype of Finnish composers taking their inspiration solely from natural landscapes.

Before writing Flounce, Wennäkoski had composed much longer compositions, some running as long as 85 minutes. She therefore had to focus her musical ideas to fit within the framework of the BBC Radio 3 commission for a five-minute work. With other works Wennäkoski had been inspired by a fabric or a fragment of a poem; in this case it was a single word—flounce—that guided her musical planning. She was drawn to the dual definition of the word, which can be used either as a verb, meaning to move with exaggerated impatience or anger, or as a noun, describing a frill or ruffle on a piece of fabric.

The work emulates its title with gestures of frustration (almost as if the orchestra is throwing a childish tantrum) and exaggerated shifts in tone color (like cutting from bright brass to warm winds and strings). Wennäkoski explains that she hoped to integrate a brisk energetic pulse with a certain sense of spaciousness. The piece contains slower, sparse, sparkly moments, although the rollicking winds and brass at times give off the impression of a fanfare. Wennäkoski says of her compositional process that “a feeling of air, space, and clarity” were important, in addition to “exciting timbral qualities.” Lurches between and within moments of both fullness and airiness convey an ongoing sense of eagerness.

Adapted from a note by Rebecca Lentjes © 2018

| First performance | September 9, 2017, at the BBC Proms, the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sakari Oramo |

| First and most recent SLSO performances | September 28 and 29, 1918, conducted by Hannu Lintu |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes (1 doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, bassoon, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 6 minutes |

Teoton – A Sheng Concerto

Jukka Tiensuu

Born 1948, Helsinki, Finland

If Jukka Tiensuu were sitting beside you at this concert, he would probably suggest you close your program right now and simply listen to his music. He has comprehensively declined to provide program notes for his works, considering it “mischievous” to burden open-minded listeners with unnecessary prejudices that narrow focus. The thoughts of the composer are not as important, he says, as the thoughts and insights the music might arouse in listeners. “I’d rather have everyone’s associations fly freely and let the music speak for itself—which it does only better when the creator gets out of the way.”

Tiensuu’s musical training was rich and diverse, encompassing piano, harpsichord, historically informed performance, conducting, composing, and electroacoustic and computer music, through studies at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, the Juilliard School, the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg, and IRCAM in Paris. As with many composers of his generation, he began his career in the 1970s as an uncompromising modernist with experimental instincts. A concerto for his own instrument, the harpsichord, tuned the two keyboards differently to create micro- intervals; he explored techniques such as aleatory (randomness and chance) and strict serialism. In the 1980s, however, he adopted the aesthetic principles of classicism, with works such as the Tango lunaire, a tango parody for chamber orchestra that became one of his popular hits, as did his clarinet concerto Puro (1989).

He has since become one of Finland’s most influential composers. When he was awarded the Wihuri Sibelius Prize in 2020, the jury praised his music for its deep spirituality and unwavering adherence to artistic goals: “Tiensuu’s musical language does not shy away from compromise, but at the same time, his music often embodies pure joy, and even humor.” Over the years, his music has been characterized as radiant, enchanting, inventive, “rigorously intelligent, sonically lustrous, and delightfully irreverent,” and “ingeniously fun … giddy, sunny and seductive” (New York Times)—all qualities that emerge in Teoton.

Concertos form the backbone of Tiensuu’s orchestral output, with 23 works featuring soloists ranging from the “standard” piano, violin, or cello to more unusual instruments such as quarter-tone accordion and the sheng. Emerging in China more than 3,000 years ago, the sheng is a free-reed mouth organ constructed from a bundle of bamboo reeds and encased in a metal bowl. As one critic has described it, it looks a little like the bottom section of a contrabassoon, with a sound that ranges from the quality of a harmonica in its higher registers to an English horn at the low end. Chinese tradition likens its reedy sound to the singing phoenix of legend: silvery and fleeting as the wind.

Teoton was commissioned in 2015 by five orchestras from South Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, France, and Taiwan, with master sheng virtuoso Wu Wei as its dedicatee. Its US premiere by the Minnesota Orchestra in 2024 (also conducted by Dima Slobodeniouk) was described as an “ovation-inducing delight” that stole the show.

True to form, Tiensuu provides no guidance for this piece beyond the evocative names he has assigned to its four transporting movements. These are performed without a break, but are clearly defined by shifts in character: Fever, Adrift, Game, and Bliss. Now listen…

Yvonne Frindle © 2026

| First performance | October 30, 2015, by the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Ilan Volkov |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | solo sheng; 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 26 minutes |

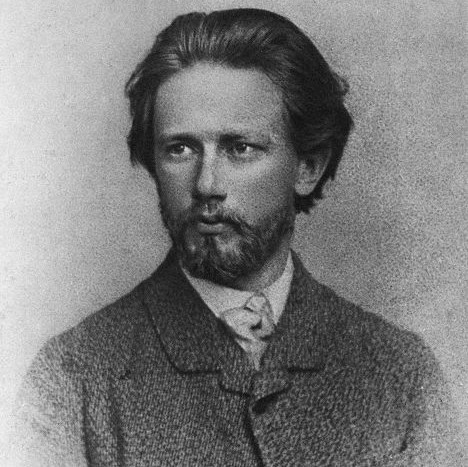

Symphony No. 4

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born 1840, Votkinsk, Russia

Died 1893, St. Petersburg, Russia

“The Introduction is the kernel of the whole symphony, without question its main idea. This is Fate, the force of destiny…”

This could be a description of the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. But the words are Tchaikovsky’s and they describe the strident horn fanfares of his Fourth Symphony, which have the same ominous character as Beethoven’s famous “da da da dum.”

The tone is set for a powerful and profound emotional drama, and Tchaikovsky’s patron, Nadezhda von Meck, heard this. After the premiere of the Fourth Symphony in 1878, she asked Tchaikovsky whether the symphony had a definite program, a literary underpinning. Another of the first listeners, a student of Tchaikovsky’s, said outright that the symphony gave off the whiff of program music—it wasn’t a compliment.

Tchaikovsky told his student that “of course” the symphony was programmatic, “but this program is such that it cannot be formulated in words.” But for von Meck, who paid his bills, Tchaikovsky went to the trouble of finding those words, although he stressed that the music had come first:

You ask whether the symphony has a definite program. Usually when I am asked this question about a symphonic work I answer, “None at all!” And in truth, it is a hard question to answer. How shall I convey those vague sensations one goes through as one composes an instrumental work without a definite subject? It is a purely lyrical process …

In our symphony there is a program (that is, the possibility of explaining in words what it seeks to express) … Of course, I can do this here only in general terms.

The Introduction is the kernel of the whole symphony, without question its main idea. This is Fate, the force of destiny, which ever prevents our pursuit of happiness from reaching its goal … It is invincible, inescapable. One can only resign oneself and lament fruitlessly. This disconsolate and despairing feeling grows ever stronger and more intense. Would it not be better to turn away from reality and immerse oneself in dreams?

Tchaikovsky continues, identifying musical ideas that represent tender dreams and fervent hope, then a climax suggesting the possibility of happiness, before the Fate theme awakens us from the dreams …

And thus, all life is the ceaseless alternation of bitter reality with evanescent visions and dreams of happiness … There is no refuge. We are buffeted about by this sea until it seizes us and pulls us down to the bottom. There you have roughly the program of the first movement.

All this matches the emotional character of the first movement—what Tchaikovsky called the music’s “profound, terrifying despair”—and if we allow for Tchaikovsky’s personal turmoil at the time (he’d just emerged from an ill-advised marriage) then an autobiographical interpretation is plausible. More striking, though, is Tchaikovsky’s handling of his two principal ideas: Fate and “self.” Fate is the fanfare; self is the first real melody, to be played “in the character of a waltz.” What is less apparent, as Richard Taruskin has pointed out, is that the Fate “fanfare” is really a polonaise.

These two ideas collide in the music. Copying a dramatic strategy from Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, Tchaikovsky superimposes the two dances, matching three measures of waltz-time to one measure of the slower, more aristocratic polonaise (also in three). Then, in the coda, we hear the “complete subjection of self to Fate” and the waltz returns one last time, stretched to match the pulse of the polonaise—hardly a waltz at all. This is just one of the ways in which the first movement behaves more like a tone poem than a symphony.

The effect of this collision is one of music, and a composer, torn between extremes. Tchaikovsky’s instinct was for lyrical outpourings (that glorious waltz), but he understood that to be a composer of symphonies in 1878 meant observing the conventions established by Beethoven. The Fate fanfare gave him a motto he could manipulate in the same way that Beethoven manipulates the “Fate knocking” motto of his Fifth.

In addition to the symphony’s programmatic character, there was something else that Tchaikovsky’s student, Sergei Taneyev, noticed with disapproval: “the first movement is disproportionately long” and has “the appearance of a symphonic poem to which three movements have been appended fortuitously to make up a symphony.”

Many commentators have agreed. Tchaikovsky’s descriptive program provides a wealth of detail for the first movement, but then peters out. The nostalgic second movement is summed up as an expression of “the melancholy feeling that arises in the evening as you sit alone, worn out from your labors.” And the Scherzo, he claims, expresses no definite feelings at all: “One’s mind is a blank: the imagination has free rein.” But the Scherzo doesn’t suffer for this. It’s one of the most effective parts of the symphony, famous for its use of pizzicato strings throughout—the relentless plucking combined with brilliant and inventive writing for the woodwinds and brass, in particular the scampering piccolo.

In the Finale, Tchaikovsky chooses a folk song, “The Birch Tree,” as the theme for a set of variations. He describes the movement as a picture of popular holiday festivity, but this apparently cheerful scenario is given a depressing cast: “If you can find no impulse for joy within yourself, look at others … Never say that all the world is sad. You have only yourself to blame … Why not rejoice through the joys of others?” It’s as if we’re meant to hear the finale as festivity—but secondhand. If this isn’t resignation to Fate, nothing is.

Yvonne Frindle © 2018/2026

| First performance | February 2, 1878, in Moscow, the orchestra of the Russian Music Society conducted by Nikolai Rubinstein |

| First SLSO performance | December 22, 1910, conducted by Max Zach |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 20, 2021 at the University of Missouri, Columbia, conducted by Stephanie Childress; the most recent St. Louis performance was October 1, 2021, conducted by Stéphane Denève |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 44 minutes |

Artists

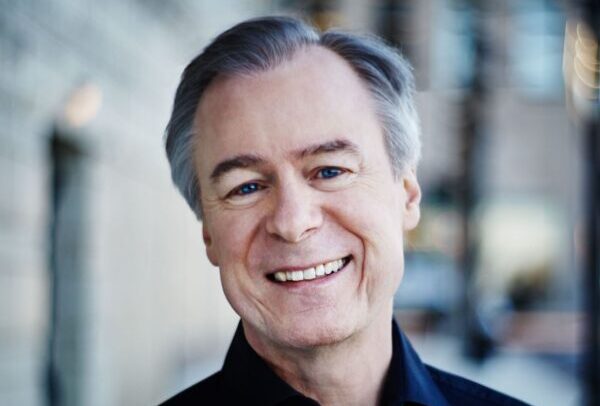

Dima Slobodeniouk

Dima Slobodeniouk studied with violinist Olga Parkhomenko at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, where he also studied conducting with Leif Segerstam, Jorma Panula, and Atso Almila. Acclaimed for his dynamic leadership and exhilarating interpretations, he has conducted leading orchestras such as the Berlin Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, Vienna Symphony, Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, and NHK Symphony Orchestra. He has served as Music Director of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia (2013–2022), and from 2016 to 2021 he was Principal Conductor of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra and Artistic Director of the International Sibelius Festival.

In addition to his SLSO debut, this season he conducts the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland Orchestra, the Boston and Pittsburgh symphony orchestras, San Francisco Symphony, and Houston Symphony. Other season highlights include conducting the Seoul Philharmonic (Lotte Hall Festival), WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne, Dresden Philharmonic, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Bergen Philharmonic, Antwerp Symphony Orchestra, and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra’s New Year’s Eve concerts.

Notable recordings include Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Cello Concerto (Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and Nicolas Altstaedt), which received an ICMA Award, an all-Stravinsky album (Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia), music by Kalevi Aho (Lahti Symphony Orchestra), which won the 2018 BBC Music Magazine Award, followed by Aho’s Sieidi and Fifth Symphony, and an album of music inspired by the Kalevala. He has also recorded works by Perttu Haapanen and Lotta Wennäkoski (Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra).

Wu Wei

The artistry of internationally renowned sheng virtuoso Wu Wei reaches beyond the boundaries of his 3,000-year-old instrument, bringing it into the 21st century with a vast repertoire of both traditional Chinese and Western music, ranging from baroque to electronics and jazz. The infinite possibilities offered by his instrument have led to collaborations with leading artists and composers in traditional chamber and orchestral settings; improvising with jazz big bands; and interdisciplinary projects involving literature, dance, and theater.

Wu Wei was born in 1970 in Gaoyou, China. In 1995, after studying at the Shanghai Conservatory, he took part in a four-year DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) scholarship at the Hanns Eisler Conservatory in Berlin, where he now lives. In 2013, he was appointed professor of the sheng at the Shanghai Conservatory.

He has commissioned new works for the sheng and premiered more than 200, including concertos and chamber music by composers such as Unsuk Chin, Jukka Tiensuu, Toshio Hosokawa, Jörg Widmann, and Tan Dun. His extensive discography includes a recording of Unsuk Chin’s Sheng Concerto, which won the 2015 BBC Music Magazine Award.

Appearances with Western ensembles have included the Los Angeles, New York, and Berlin philharmonic orchestras, Lucerne Festival Contemporary Orchestra, Holland Baroque, Ensemble intercontemporain, Atlas Ensemble, and NDR Big Band. He regularly performs in festivals such as the BBC Proms, Festival d’Automne à Paris, Donaueschinger Musiktage, Lucerne Festival, Suntory Hall Summer Festival (Tokyo), and Tongyeong International Music Festival, and most recently at the 2025 Ojai Music Festival.

Current projects include a residency in 2025/26 with the NCPA Orchestra in Beijing, and the premiere of Philippe Leroux’s concerto for sheng, ensemble, and electronics at the Festival Manifeste 2027.