Symphonie fantastique (September 27 & 29, 2024)

Program

September 27 & 29, 2024

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Gil Shaham, violin

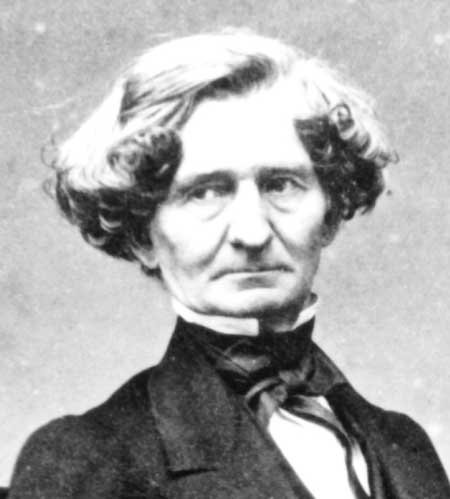

Hector Berlioz (1803–1869)

- Rákóczi March

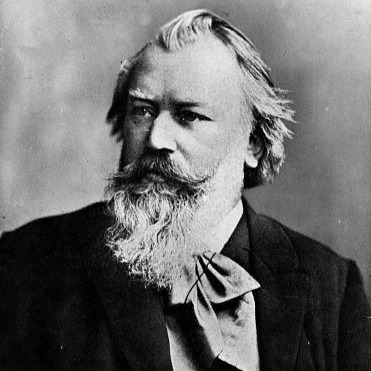

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

- Hungarian Dances

- No. 1 in G minor (Allegro molto)

No. 3 in F major (Allegretto)

No. 10 in F major (Presto)

- No. 1 in G minor (Allegro molto)

Mason Bates (b. 1977)

- Nomad Concerto

- Song of the balloon man

Magician at the bazaar

Desert vision: oasis

Le jazz manouche

- Song of the balloon man

Gil Shaham, violin

Intermission

Berlioz

- Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14

- Daydreams (Largo) – Passions (Allegro agitato

e appassionato assai)

A Ball (Valse. Allegro non troppo)

In the Fields (Adagio)

March to the Scaffold (Allegretto non troppo)

Sabbath Night Dream (Larghetto – Allegro –

Dies irae – Sabbath Round (Un peu retenu) –

Dies irae and Sabbath Round together)

- Daydreams (Largo) – Passions (Allegro agitato

Opening Weekend

Our opening weekend program begins with outsider impressions of “Hungarian” music. According to his memoir, Hector Berlioz completed his orchestral version of the Rákóczi March in “the course of one night,” while en route to what is now Budapest—predicting that this rousing number, based on traditional tunes, would win over his new Hungarian audience. He was right. His “Marche hongroise” stimulated such patriotic fervor,

“it was almost frightening, it was sublime.”

Johannes Brahms’s Hungarian Dances—similarly “nurtured” from traditional melodies—won him comparable acclaim. They were so popular in their original piano duet versions that his publisher commissioned various arrangements, as well as orchestral versions from Brahms and other composers such as Antonín Dvořák. The three we perform in this concert are those that Brahms orchestrated himself.

The Nomad Concerto, composed for violinist Gil Shaham and heard here in St. Louis for the first time, is like a musical caravan, exploring, in the words of Mason Bates, “the mysterious and soulful music of the wanderer.”

As listeners, we journey through styles from Europe to the Middle East before arriving in an imagined jazz club of 1930s Paris.

We remain in Paris after intermission, but are taken even deeper into the realm of the imagination with Hector Berlioz’s “fantastical” symphony—a musical fever dream in which a young artist pursues an obsession to its terrible, thrilling conclusion.

Rákóczi March

Hector Berlioz

Born 1803, La Côte-Saint-André, France

Died 1869, Paris

The Rákóczi March originated almost a century and a half before Hector Berlioz made his famous version in 1846. The title refers to Francis II Rákóczi, a Hungarian nobleman who led an unsuccessful revolution against the Habsburgs between 1703 and 1711. He ended up in exile in Poland, but a song associated with his movement lived on among Hungarians. By the 1820s, it began to appear in print, including in an anonymous version arranged as a military march with embellished folk elements.

Béla Bartók, the 20th-century Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist, noted the march’s diverse influences, including “Arabic-Persian ‘long melody,’ Eastern European-Hungarian elements, and ornamental motives of Central European art music.” Nevertheless, he thought, “the way they are transformed, melted, and unified presents as a final result a masterpiece of music whose spirit and characteristics are incontestably Hungarian.”

In 1846, seeking success beyond his Parisian home, Berlioz toured to Pest (later merged into Budapest), where he put on an orchestral concert of his own music. He came prepared with an arrangement of the Rákóczi March to help win over the Hungarian audience. Always a colorful commentator, Berlioz recalled:

People speculated as to how I had treated the famous, nay, the sacred melody, which for so long had set the hearts of Hungarians aflame with a holy passion for glory and liberty. There was even some anxiety about it, a fear of profanation.… After a trumpet fanfare based on the rhythm of the opening bars, the theme, as you will recall, is announced piano by flutes and clarinets accompanied by pizzicato strings. During this unexpected exposition the audience remained calm and silent. But when a long crescendo ensued, with fragments of the theme reintroduced fugally, broken by the dull thud of the bass drum, like the thump of distant cannon, the whole place began to hum with excitement; and, as the orchestra unleashed its full fury and the long-delayed fortissimo burst forth, a tumult of shouting and stamping convulsed the theater: the accumulated pressure of that boiling mass of emotion exploded with a violence that sent a thrill of fear through me.… The thunders of the orchestra were powerless against that erupting volcano; nothing could stop it. We had to repeat the piece, of course.

After the concert, one excited Hungarian listener approached Berlioz backstage to say, in broken French, “In heart of me you stay—ah, French—Republican—know to make music of Revolution!” Berlioz later included the arrangement as the ‘Marche Hongroise’ in Part 1 of The Damnation of Faust, his more-or-less unstageable opera (or légende dramatique, as he called it) based on Goethe’s play. There it accompanies a passing army while Faust mopes in his study, unroused.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2024

| First performance | February 15, 1846 at a concert in Pest (now Budapest), Hungary |

| First SLSO performance | December 8, 1907, conducted by Max Zach |

| Most recent SLSO performance | June 2, 2019, conducted by Gemma New; the March was also heard as part of The Damnation of Faust, conducted by Stéphane Denève on May 6, 2023 |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 5 minutes |

Hungarian Dances Nos. 1, 3, and 10

Johannes Brahms

Born 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died 1897, Vienna, Austria

If Germany and Austria were at the center of 19th-century European music, then Hungary was the closest neighbor with a distinct tradition—filled with syncopated rhythms, husky melodies, and flashy runs. Johannes Brahms heard Hungarian music as a teenager in 1848 when a group of refugees passed through his native Hamburg on their way to the United States. Among them was Ede Reményi, a violinist and composer with whom he later toured as a pianist. So Brahms certainly had firsthand experience with practitioners of this music, but was not too concerned with authenticity or ethnology—Hungarian and “Gypsy” (more properly, Romani) music were treated as synonymous, and recent music composed in a national style was sometimes conflated with folk music. It was all mixed into the style hongrois—the Austro-German impression of how things generally sounded to their southeast.

Brahms wrote his first ten Hungarian Dances around 1868, and later brought the number up to 21. Originally conceived for piano four hands, he also made versions for a single pianist, and then orchestrated the three dances on this program (the rest were later orchestrated by other composers).

Writing to his publisher, Fritz Simrock, Brahms claimed: “These are, by the way, genuine children of the Puszta [Hungarian Great Plains] and the Gypsies, that is to say, not begot by me, rather only nurtured with milk and bread.” The violinist Reményi, however, claimed authorship of some of the tunes, as did another Hungarian composer, Béla Kéler, whose own publisher lodged a protest with Simrock.

Still, the pieces must have been close to Brahms’s heart. In 1889, when an assistant to Thomas Edison came to make a wax cylinder recording, the elderly composer chose to play part of Hungarian Dance No. 1 at the piano. Though almost unintelligible, it’s the only audio record we have of Brahms himself, and you can just barely make out the familiar contours of the melody through all the crackle.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2024

| First performance | February 5, 1874 in Leipzig, Brahms conducting the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | Hungarian Dances Nos. 1, 3 and 10 on March 4, 1909, conducted by Max Zach |

| Most recent SLSO performance | Hungarian Dances Nos. 3 and 10 on December 13, 2014, conducted by Steven Jarvi; No. 1 on December 31, 2013, conducted by David Robertson |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

Nomad Concerto

Mason Bates

Born 1977, Philadelphia

Bates’s Nomad Concerto was commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra and San Diego Symphony for violinist Gil Shaham. The composer provides this description of the piece:

Nomad Concerto explores the mysterious and soulful music of the wanderer. Envisioned to showcase the legendary Old World sound of Gil Shaham, the concerto is informed by a diverse range of traveling cultures from Eastern Europe to the Middle East. In the same way that nomadic musics have continually reimagined themselves, the many styles informing the concerto are swirled together into a unique sound world.29

The concerto’s opening movement (Song of the balloon man) imagines an old balloon seller wandering through a village as he sings a doleful tune, which is gradually picked up by the villagers. The music draws from a variety of elements of the European Roma, with the soloist sometimes using a strumming pizzicato effect suggestive of mandolin. The movement is followed by the short, scherzo-like Magician at the bazaar, showcasing quicksilver violin figuration that the orchestra transforms into shimmering and gossamer textures.

Over haunting orchestral expanses depicting the vast deserts of the Middle East, the Jewish folk tune “Ani Ma’amin” unfolds in Desert vision: oasis. The movement’s heaviness temporarily brightens at the vision of a sparkling oasis. A propulsive finale (Le jazz manouche) is animated by the “minor swing” of 1930s jazz clubs, as epitomized by the legendary guitarist Django Reinhardt of the Manouche clan.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2024

| First performance | January 26, 2024, Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra with Gil Shaham as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | solo violin, 2 flutes (doubling piccolos and alto flute), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, bongo, djembe, drum kit, finger cymbals, glockenspiel, rutes, tambourine, Thai gong, triangles, wood blocks, harp, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 27 minutes |

Symphonie fantastique

Berlioz

A BAD TRIP. In 1969, during one of his celebrated Young People’s Concerts, Leonard Bernstein called Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique “the first psychedelic symphony in history.” Summarizing its storyline, he quipped, “Berlioz tells it like it is. You take a trip, you wind up screaming at your own funeral.” But Bernstein was simply paraphrasing the composer’s own program notes, which Berlioz maintained were indispensable for a complete understanding of his work. Previous symphonies—such as Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, which also comprises five movements and was a major influence on Symphonie fantastique—depicted landscapes, moods, and even events, but none had told a story so explicitly, identifying the ways in which various melodies and sound effects correspond to specific characters and plot points.

Essentially, Symphonie fantastique is an opera without singers. Today we recognize Berlioz’s symphonic debut as the archetypal program symphony—music that describes characters, events, and emotions, as opposed to absolute music, which is, at least theoretically, nonrepresentational. But audience members at the 1830 Paris premiere were unprepared for such detailed notes, particularly on such a sordid topic.

THE PROGRAM. A sensitive young artist (an obvious proxy for the composer) falls desperately in love with a total stranger (clearly the Irish actress Harriet Smithson, whom Berlioz had been stalking, to no avail, since he’d seen her play Ophelia in Hamlet three years earlier); attempts to poison himself with opium; but instead has a nightmare about murdering his beloved, being condemned to death by guillotine, witnessing his own execution, and attending his own funeral in the company of ghouls, witches, and devils.

DETRACTORS AND DEFENDERS. To many 19th-century listeners, the music was as depraved as the subject matter. Felix Mendelssohn’s

reaction was not atypical: he described it as “utterly loathsome,” its musical ideas expressed in “perverted caricatures” with exaggerated orchestral gestures. But the work also attracted passionate defenders, such as Camille Saint-Saëns and Franz Liszt. Moreover, despite the premiere’s many technical hitches, Berlioz described it in a letter two days later as a “furious success”: “The Symphonie fantastique was welcomed with shouting and stamping; they demanded a repetition of the [fourth movement]; and the [final movement] destroyed everything with Satanic effect!”

ROMANTICISM AND BEYOND. In Symphonie fantastique, the composer realized his dream of a new art form, one that comprised music, literature, and autobiography. The symphony has come to both apotheosize the Romantic era and move beyond it. His idée fixe—the recurrent melody that symbolizes the beloved and unifies the five movements—predated the Wagnerian leitmotiv, and his often bizarre orchestral sonorities (such as the col legno passages in the final movement, when the strings play with the wood rather than the hairs of their bows, creating a sound like rattling skeletons) anticipated similar experiments by avant-garde 20th-century composers.

The feverish first movement bears only a passing resemblance to sonata form. The second movement, an elegant waltz, contrasts a ballroom party (two harps) with the protagonist’s subjective experience (obsessive torment), culminating in a dazzling polyphonic display when the two worlds collide. In the third movement, subverted pastoral conventions become yet another means to convey the artist’s isolation and despair. Listen for the English horn and an offstage oboe in a call-and-response duet between two shepherds.

The sonic equivalent of a decapitation serves as the climax to the nightmarish fourth movement (March to the Scaffold). In the finale, the beloved’s theme, once “noble and shy,” devolves into a vulgar jig voiced by a shrill clarinet, and then dancing witches enact a burlesque parody of the Catholic plainchant Dies irae from the Requiem mass. Shock value aside, Symphonie fantastique is a singular achievement—epitomizing a stylistic movement that had barely begun and hurling it into the future.

Adapted from notes by René Spencer Saller © 2013, 2024

| First performance | December 5, 1830, at the Paris Conservatoire, conducted by François-Antoine Habaneck |

| First SLSO performance | November 11, 1910, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 12, 2019, conducted by Stéphane Denève |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, 4 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 cornets, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 tubas, 2 timpani, percussion, 2 harps, strings |

| Approximate duration | 58 minutes |

Artists

Gil Shaham

Gil Shaham’s flawless technique combined with his inimitable warmth and generosity of spirit has solidified his renown as an American master. He is sought after for concerto appearances with leading orchestras and conductors, and regularly gives recitals—performing with his longtime duo partner, pianist Akira Eguchi—and appears with ensembles on the world’s great concert stages and at the most prestigious festivals.

Concerto appearances include the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston and Chicago symphony orchestras, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, and San Francisco Symphony, as well as multi-year residencies with the orchestras of Montreal, Stuttgart, and Singapore, and he is a regular visitor to St. Louis.

He has more than two dozen concerto and solo recordings to his name, including 1930s Violin Concertos, Virtuoso Violin Works, Elgar’s Violin Concerto, Hebrew Melodies, The Butterfly Lovers, and an acclaimed recording of J.S. Bach’s complete sonatas and partitas for solo violin. He has earned multiple Grammys, a Grand Prix du Disque, Diapason d’Or, and Gramophone Editor’s Choice, and his second volume in the series 1930s Violin Concertos (Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto and Bartok’s Violin Concerto No. 2) and his 2021 recording of the Beethoven and Brahms concertos with The Knights were both nominated for Grammy awards.

Gil Shaham was born in Illinois and began violin studies with Samuel Bernstein of the Rubin Academy of Music in Israel at age seven. In 1981 he made debut appearances with the Jerusalem Symphony and the Israel Philharmonic orchestras, and the following year, won Israel’s Claremont Competition. This was followed by studies at Juilliard and Columbia University. He received an Avery Fisher Career Grant in 1990, and in 2008 the coveted Avery Fisher Prize. In 2012, he was named Instrumentalist of the Year by Musical America.

He plays the 1699 “Countess Polignac” Stradivarius and an Antonio Stradivari violin (c.1719), with the assistance of Rare Violins In Consortium. He lives in New York City with his wife, violinist Adele Anthony, and their three children.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.