Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (March 1-2, 2025)

Program

March 1-2, 2025

Gemma New, conductor

Susanna Phillips, soprano

Sasha Cooke, mezzo-soprano

Jamez McCorkle, tenor

Nathan Berg, bass-baritone

St. Louis Symphony Chorus | Erin Freeman, director

Kevin Puts (b. 1972)

- Hymn to the Sun

Johann Sebatian Bach (1685-1750)

orch. by Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

- Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537

Intermission

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

- Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 (Choral)

- Allegro ma non troppo e un poco maestoso

- Molto vivace – Presto

- Adagio molto e cantabile – Andante moderato

- Presto – Recitativo “O Freunde, nicht diese Töne!”– Allegro assai (Choral Finale on Schiller’s Ode to Joy)

Susanna Phillips, soprano

Sasha Cooke, mezzo-soprano

Jamez McCorkle, tenor

Nathan Berg, bass-baritone

St. Louis Symphony Chorus | Erin Freeman, director

Program Notes

Hymn to the Sun

Kevin Puts

Born 1972, St. Louis, Missouri

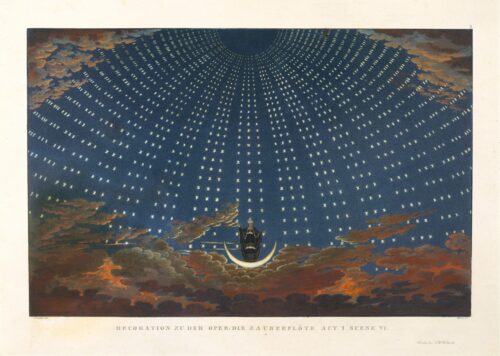

St. Louis-born composer Kevin Puts wrote Hymn to the Sun in 2008 for the Sun Valley Summer Symphony in Idaho. The title might appear to be a riff on the festival’s name, but Puts took his inspiration from what he describes as an “ancient Egyptian appeal to the deific sun.” It’s hardly the first classical work inspired by Egyptian mythology, from the 18th century to the present day: Mozart’s Magic Flute (“O Isis und Osiris”), Verdi’s Aida, and Philip Glass’s Akhenaten all come to mind.

Puts describes his concept for the music this way:

I imagined a wild, sacred dance to call forth the sun and all its powers, and then the sudden and magnificent rising on the horizon. The image of the sun’s rays binding all the lands is particularly moving to me in the context of today’s tense global climate. During the time I composed this piece, I had the amazing fortune of witnessing the sun’s rising from the summit of Mount Haleakalā on the Hawaiian island of Maui, an experience Mark Twain described as the “sublimest spectacle” of his life.

Kevin Puts (pronounced like the verb “puts,” not as in golfing “putts”) won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for his opera Silent Night and the 2023 Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Classical Composition for Contact, his concerto for two violins and double bass, and in 2024 he was named Musical America’s Composer of the Year. His music has been commissioned and performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra, Carnegie Hall, Opera Philadelphia, Minnesota Opera, and cellist Yo-Yo Ma. SLSO performances of his music have included Silent Night Elegy in 2020—paired, as it happens, with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—and in 2023 the SLSO and Stéphane Denève commissioned and premiered his Concerto for Orchestra.

In 2022, his fourth opera, The Hours, received its concert premiere in Philadelphia (conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, with today’s tenor soloist as Leonard Woolf), followed by its triumphant stage premiere at the Metropolitan Opera with Renée Fleming, Kelli O’Hara, and Joyce DiDonato. Its revival in 2024 marked the first instance in the Metropolitan Opera’s history of a work returning the season after its premiere.

Puts teaches composition at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore and is currently the director of the Minnesota Orchestra Composer’s Institute.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | August 3, 2008 at the Sun Valley Summer Symphony, conducted by Alasdair Neale |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

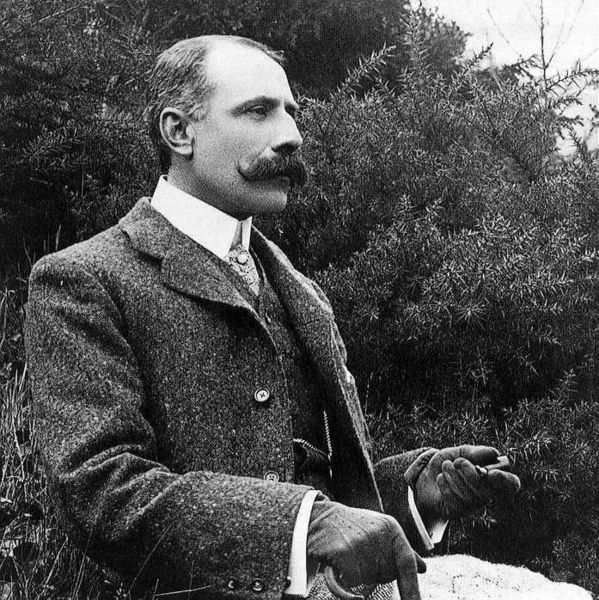

Fantasia and Fugue, BWV 537

Johann Sebastian Bach

Born 1685, Eisenach, Germany

Died 1750, Leipzig, Germany

Arranged by

Edward Elgar

Born 1857, Broadheath, England

Died 1934, Worcester, England

The death of Elgar’s wife in 1920 had a devastating effect on the composer.

It was a year before he was able to enjoy music again, playing the big organ fugues of Bach that he’d learnt 40 years earlier. He began arranging the music of other composers, telling the conductor Eugene Goossens, “now that my poor wife has gone I can’t be original, and so I depend on people like John Sebastian for a source of inspiration.”

Elgar decided to orchestrate Bach’s C minor fugue for organ (BWV 537), writing to Ivor Atkins: “I wanted to show how gorgeous and great and brilliant he would have made himself sound if he had our means.” Work on the fugue was finished in April 1921 and on October 27 Goossens conducted the premiere.

The following January, Elgar hosted a lunch for the visiting German composer Richard Strauss, and there was a discussion of transcribing Bach’s organ music for orchestra. (Elgar favored the “modern way” with a large orchestra; Strauss a more restrained approach.) Strauss was challenged to make his own orchestration of the fantasia that preceded Bach’s fugue, but he declined, and Elgar decided to do it himself, conducting the completed work at the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival in 1922. Why it was felt that an orchestra could make Bach’s music sound more impressive than Gloucester Cathedral’s organ is a good question, but it remains that Elgar conceived his orchestration with such a setting in mind.

The original Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537 may belong to Bach’s time at Weimar (1708–17), but an unusual formal feature of the fugue, occasionally found in his later works, has led some to think the music belongs to his time in Leipzig, after 1723.

Elgar’s treatment of the mournful Fantasia, a kind of processional in triple time, with drum strokes, shows a Romantic insight into the emotional essence of the piece, and reminds the listener of his love for Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. The heavier scoring is reserved for the climax, but the full orchestra comes into its own in the Fugue, brass well to the fore, with brilliant splashes for winds, harp, and percussion, ending with a tremendous orchestral equivalent of the full opening of the organ swell box.

Later in the 1920s, there was a rash of orchestral transcriptions of Bach’s organ music, the most famous being Stokowski’s of the Toccata and Fugue in D minor (1927) that opens Disney’s Fantasia. But Elgar’s—controversial at first among organists and Bach-lovers—has been one of the few to keep a place in the concert repertoire. This is a testament to its achievement—more than transcription, it is a commentary by one creative musician finding affinity in another.

Abridged from a note by David Garrett © 2005

| First performance | Eugene Goossens conducted the first performance of the Fugue on October 27, 1921; the composer himself conducted the premiere of the complete pairing at the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival on September 7, 1922 |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, 2 harps, strings |

| Approximate duration | 9 minutes |

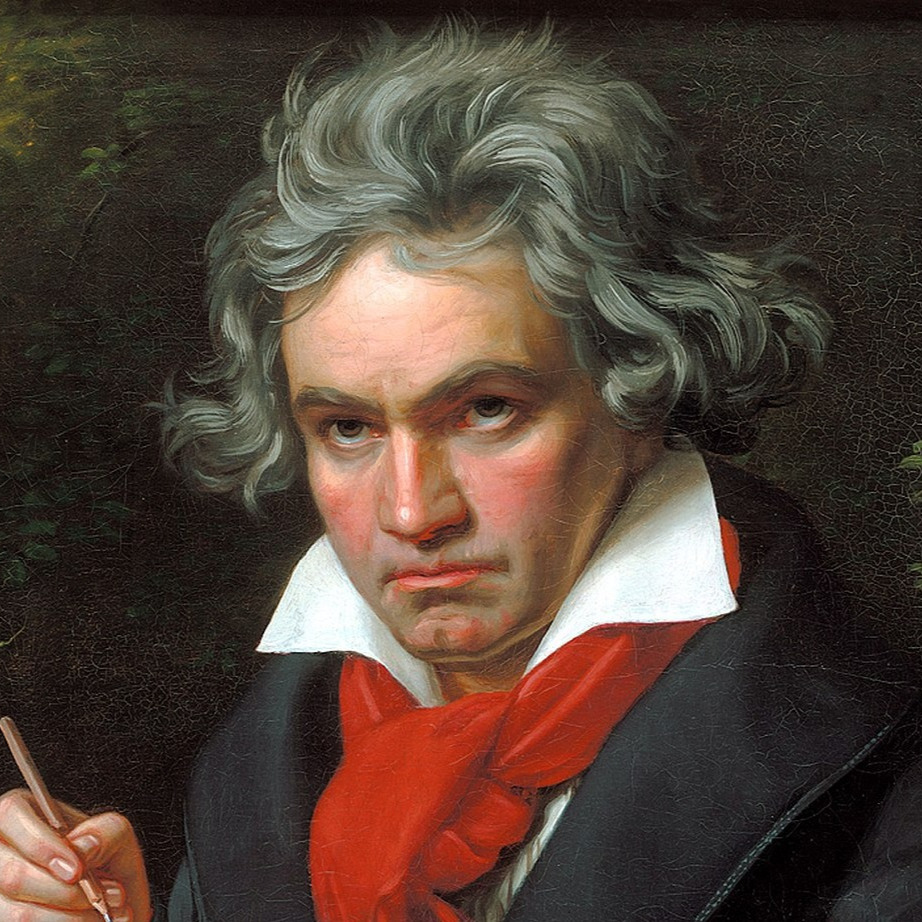

Symphony No. 9 (Choral)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died 1827, Vienna, Austria

A cramped city apartment is strewn with clothes, plates of rotting food. At a table sits a short, stocky man, hunched over a mess of papers. Although 52, Beethoven looks much older. He is in constant physical and emotional pain, and rarely appears in public, self-conscious about his total deafness. Against all odds he still believes in the power of his music. Beethoven leans over a copy of the popular ode, An die Freude (To Joy), by Friedrich Schiller. He is at work on a new symphony—a work so massive, so experimental, that it’s without precedent.

Beethoven doesn’t know it yet, but this symphony will be his final public success. It may baffle generations of listeners, but a cult following will grow until the music of the Ninth criss-crosses the globe, used for political rallies and TV shows, used to unite as well as to divide.

Liberty above all things

Thirty years earlier, when the young Beethoven first read this ode, Friedrich Schiller was Germany’s most popular writer, a free-spirited libertine who enjoyed rock-star adulation. The language of his ode, or poem, in praise of “joy” is intoxicating, almost erotic—Schiller himself later judged it over-the-top. But the ode, written in 1785, appealed to the optimistic mood of pre-French Revolution Europe and was a hit, sung over beers at parties across Germany.

Beethoven, loving “liberty above all things,” may have been drawn to the poem’s politics. In the ode, freedom and joy are linked: joy provides a path to moral goodness for all of humanity. Schiller’s first version of the poem called for “rescue from the chains of tyrants.” And at age 22, Beethoven sketched a setting of An die Freude for voice and piano. It lay unfinished, but Beethoven never forgot the power of Schiller’s words.

Returning to the ode

In 1822, Beethoven was finding his way out of a long creative drought. Life had been difficult for this middle-aged man, but he’d recently completed works that redefined their genres: an epic mass setting and a set of piano variations of dizzying complexity. So, when a concrete financial offer arrived from the London Philharmonic Society, Beethoven was primed for an artistic challenge. He’d been thinking of a symphony with choir for several years, but it was an almost unsolvable, nerve-wracking problem to solve. Schiller’s An die Freude was the missing piece of the puzzle.

Why did Beethoven return to Schiller’s ode now, 30 years after he’d first read it? By 1822, the ideals of the French Revolution had been trampled by a megalomaniac. Europe had been seized by bloody wars. Austria’s monarch had turned reactionary, clamping down on liberals, artists, journalists. The ode’s optimism had soured.

Perhaps this moment—repressive, divided—was perfect for Beethoven to launch a defense of progressive ideals in the most public forum he knew: the symphony.

The first three movements

The first three instrumental movements of the Ninth build on experiments from Beethoven’s previous symphonies: expanding horizons, testing players, building complexity.

Warlike music dominates the first movement. The opening is radical—vacant, trembling—but soon the music turns furious, forceful, savage. Near the end of the movement, a march approaches. There is no triumph—the tone is dark, the tread heavy: heroic music of Beethoven’s past, gone to seed.

The second movement is no fun-loving scherzo. Beethoven has us firmly in the grip of a major key, but the fun-loving rough-and-tumble of his earlier symphonic scherzos has taken on deep shadows. The orchestra dances perilously close to the fire.

The third movement blooms like a beautiful flower. Two melodies are woven together, arm in arm. Each is simpler, more hummable than earlier Beethoven tunes, and each grows throughout the movement, blossoming in richness and complexity.

The finale

A grinding dissonance jolts. Onstage we see a choir, four soloists, but they don’t sing yet. Instead, Beethoven gives us the voices of the double basses, who launch into an operatic recitative. Their job: to stand in judgment of music from the symphony’s first three movements. The first movement: rejected. The second: rejected. The third: rejected. Beethoven is turning his back on the music of his own symphony.

But why? Is Beethoven saying that instrumental music is insufficient at this important moment? Or that this music—his music—is no longer relevant? That we should look to the future, rather than to the past? The following “Ode to Joy” is thrilling and confusing: asking more questions than it answers. It is part-opera, part-theme and variations, part-cantata, part-political speech, part-philosophical rant, part-celebratory jam.

There are triumphs: the key of D major triumphs over D minor; voices triumph over instruments; joy triumphs over division.

There are impossibilities: The choir sings notes beyond what was considered possible at the time. The orchestra attempts music that would have been unplayable by the mix of amateurs and professionals at the premiere.

There are contradictions: God plays an important role in proceedings, even though Beethoven rejected organized religion. Brotherhood plays a role, even though Beethoven had very few close friends. Music historian Richard Taruskin put it like this: Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony “is at once incomprehensible and irresistible…at once awesome and naïve.”

The Ninth Symphony’s premiere must have sounded catastrophic. Handwritten instrumental parts were messy and error-ridden, the music was impossible for the less-experienced performers on stage, and the two rehearsals were scarcely enough, especially with Beethoven—at this point completely deaf—conducting. Some were thrilled, some baffled. The 19-year-old Franz Schubert wrote in his diary that “the eccentricity which confuses the tragic with the comic, the agreeable with the repulsive, heroism with howlings, and the holiest with harlequinades.”

Tim Munro © 2020

| First performance | May 7, 1824, at the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna, with soloists Henriette Sontag, Caroline Unger, Anton Haizinger, and Joseph Seipelt; Michael Umlauf conducted, with Beethoven nominally giving tempos |

| First SLSO performance | December 21, 1928, Emil Oberhoffer conducting, with soloists Helen Traubel, Viola Silva, Laurence Wolfe, and Jerome Swinford, and the Apollo-Morning Choral Clubs |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 9, 2020, Stéphane Denève conducting, with soloists Ellie Dehn, Jennifer Johnson Cano, Issachah Savage, and Morris Robinson, and the St. Louis Symphony Chorus |

| Instrumentation | vocal soloists, mixed chorus, 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 1 hour and 5 minutes |

Artists

Gemma New

New Zealand-born Gemma New is Artistic Advisor and Principal Conductor

of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, and a sought after guest conductor.

Her 2024/25 season includes debut appearances with the Munich Radio Orchestra, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa, BBC National Orchestra & Chorus of Wales, Brussels and Netherlands philharmonic orchestras, Prague Philharmonia, and Musikkollegium Winterthur. In the United States, she returns to conduct the Milwaukee and Indianapolis symphony orchestras and the Juilliard Orchestra. Equally in demand in the UK and Europe, she returns

to the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Mendelssohn Academy Orchestra Leipzig, Kristiansand and Malmö symphony orchestras, Orchestra della Toscana, Orquesta Sinfonica de Barcelona, and Bergen Philharmonic.

She regularly conducts top orchestras worldwide, including the New York Philharmonic; the Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Minnesota orchestras; National Symphony Orchestra (Washington, DC); and the Detroit, Atlanta, Baltimore, San Diego and Montreal symphony orchestras; as well as the BBC Philharmonic, Hallé Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, WDR Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre National de Lyon, Spanish National Orchestra, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Recent highlights include subscription debuts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, and Orchestre National de France, as well as stepping in at short notice for the San Francisco Symphony and the Seattle Symphony, and a return to the BBC Proms (BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra).

From 2016 to 2020 she served as Resident Conductor of the SLSO and Music Director of the SLSYO. 2023/24 marked her ninth and final season as Music Director of the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra in Ontario. She was previously Principal Guest Conductor of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra and Associate Conductor of the New Jersey Symphony.

Gemma New holds a master’s in orchestral conducting from the Peabody Institute, where she studied with Gustav Meier and Markand Thakar. She also holds an honors degree in violin performance from the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. A former Dudamel Conducting Fellow (LA Philharmonic) and Conducting Fellow at Tanglewood Music Center, she was awarded Solti Foundation US Career Assistance Awards in 2017, 2019, and 2020, before receiving the 2021 Sir Georg Solti Conducting Award. Last year she was appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

Susanna Phillips

American soprano Susanna Phillips is well known to St. Louis audiences, with notable appearances including performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Act III of Wozzeck in 2013, Mahler’s Fourth Symphony and Vivier’s Lonely Child in 2016, and as Ellen Orford in the SLSO’s historic concert performance of Peter Grimes at Carnegie Hall in 2013. More recently, she sang Rose in the premiere of Awakenings at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis.

Other career highlights include more than 11 roles at the Metropolitan Opera, beginning with her house debut in La bohème in 2008, and singing Stella in

A Streetcar Named Desire opposite Renée Fleming (Carnegie Hall and Lyric Opera of Chicago). She has sung leading roles with Boston Baroque, including Cleopatra in Giulio Cesare and the title role in Agrippina. She has also appeared for Lyric Opera of Chicago, Cincinnati Opera, Dallas Opera, and Gran Teatro del Liceu in Barcelona.

In her symphonic repertoire, which includes Mahler symphonies, the Mozart and Fauré requiems, and Carmina Burana, she has collaborated with orchestras such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as the Huntsville Symphony Orchestra in her native Alabama. This season, her engagements include the Seattle Symphony, Musica Sacra, Oratorio Society of New York, and San Francisco Symphony.

An avid chamber music collaborator, she has performed a tribute concert to Clara Schumann at the Library of Congress and has sung alongside Eric Owens for Washington Performing Arts in a program co-curated by the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

She has won awards in some of the world’s leading vocal competitions, including the Metropolitan Opera’s Beverly Sills Artist Award and Laffont Competition, and Operalia (first place and audience prize). She is an alumna of Lyric Opera of Chicago’s Patrick G. and Shirley W. Ryan Opera Center, and holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School.

Sasha Cooke

American mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke made her SLSO debut in 2019, singing Bernstein’s Kaddish with Leonard Slatkin, and returned in 2021 for concerts with Gemma New given in memory of music critic Sarah Bryan Miller. She has sung at the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, English National Opera, Seattle Opera, Opéra National de Bordeaux, and Gran Teatre del Liceu, among others, and with more than 80 symphony orchestras worldwide, frequently performing in the works of Mahler.

This season, she makes her La Monnaie (Belgium) house debut singing Emilie Ekdahl in the premiere of Fanny and Alexander, sings Marguerite in

La Damnation de Faust (Bard Festival) and Brangäne in Tristan und Isolde

(Gstaad Festival), and returns to Houston Grand Opera as Venus in Tannhäuser. Her concert appearances include the Vienna Symphoniker, San Francisco Symphony, Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Cologne Philharmonic, Tucson Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philharmonia Orchestra, Oslo Philharmonic, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, and Slovenian Philharmonic Orchestra, collaborating with conductors such as Esa-Pekka Salonen, Marin Alsop, Cristian Măcelaru, Gustavo Dudamel, Trevor Pinnock, Klaus Mäkelä, Karina Canellakis, and Daniel Harding. She also returns to Wigmore Hall for a recital with pianist Malcolm Martineau, and Carnegie Hall for Shostakovitch’s From Jewish Folk Poetry with Evgeny Kissin.

She is a devoted interpreter of contemporary music and has premiered many new works. Highlights include the Grammy-winning recordings of Mason Bates’s (R)evolution of Steve Jobs with San Francisco Opera (singing Laurene Jobs) and John Adams’s Doctor Atomic with the Metropolitan Opera (singing Kitty Oppenheimer), both of which won Best Opera Recording, and Michael Tilson Thomas’s Meditations on Rilke with the San Francisco Symphony, which won the 2021 Grammy Award for Best Classical Compilation. Her 2022 solo album how do I find you, featuring songs by Caroline Shaw, Nico Muhly, Missy Mazzoli, and Jimmy Lopez, was nominated for a Grammy for Best Vocal Solo.

Sasha Cooke is a graduate of Rice University and the Juilliard School. She also attended the Music Academy of the West, Aspen Music Festival, Ravinia Festival’s Steans Music Institute, Wolf Trap Foundation, Marlboro Music Festival, Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artist Development Program, and the Seattle Opera and Central City Opera young artist training programs.

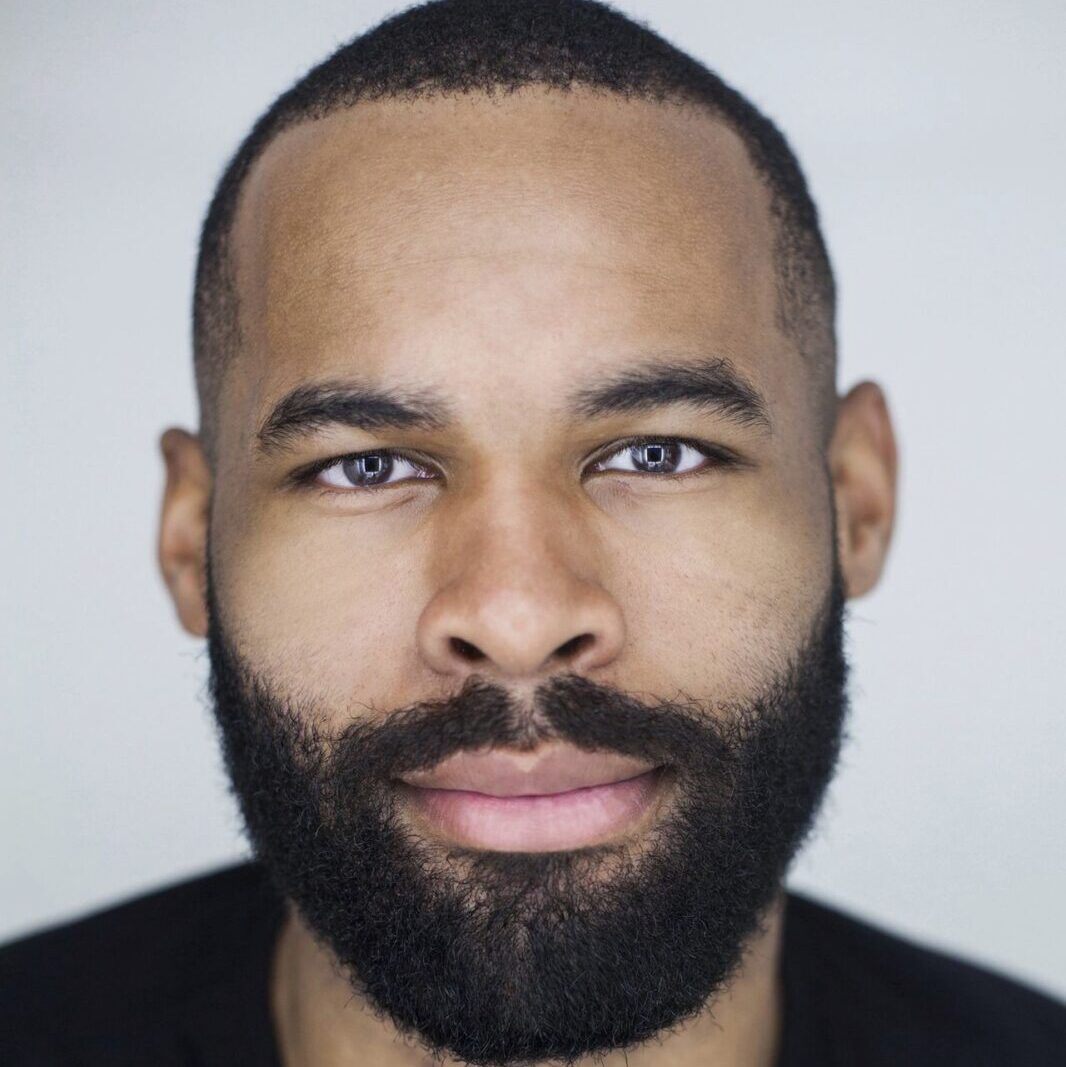

Jamez McCorkle

American tenor Jamez McCorkle made headlines after his acclaimed appearance in the title role of the Pulitzer Prize-winning opera Omar, which premiered at the 2022 Spoleto Festival and was subsequently presented at

LA Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, San Francisco Opera, and Carolina Performing Arts Center.

Recent triumphs as Bacchus in Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos (Royal Danish Opera) and Laca in Jenůfa (Opera Ballet Flanders) have led to house debuts at Royal Ballet & Opera (Covent Garden), Washington National Opera, Santa Fe Opera, and Hamburg State Opera, and concerts with the

LA Philharmonic.

This season, he makes role debuts as Florestan in Fidelio (Washington National Opera), which he also performs for Bordeaux National Opera, and as Siegmund in Die Walküre (Santa Fe Opera). For his house debut in Hamburg, he sings Bacchus in a new production of Ariadne auf Naxos. On the concert platform he appears with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra in both Das Rheingold (singing Froh) and Verdi’s Requiem.

Last season, his concert appearances included Messiah (US Naval Academy) and The Song of the Earth (Danish National Symphony Orchestra). Other recent highlights include his return to the Spoleto Festival for a staged production of Schumann’s Dichterliebe, in which he performed the song cycle accompanying himself at the piano; the Duke of Cornwall in Aribert Reimann’s Lear (Bavarian State Opera); his house and role debut as Telemaco in Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria (Theatre Basel); Peter the Honeyman in Porgy and Bess (Metropolitan Opera); Leonard Woolfe in the concert premiere of The Hours by Kevin Puts (Philadelphia Orchestra); Britten’s War Requiem (Israel Philharmonic Orchestra); Tamino in Die Zauberflöte (Kentucky Opera); Lensky in Eugene Onegin (Michigan Opera Theatre); and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (Spoleto Festival).

Jamez McCorkle is a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music, and an alumnus of Mannes College: The New School for Music and Loyola University, New Orleans. He was a member of the International Opera Studio in Zurich and took part in the Young Artist Program of the 2017 Salzburg Festival. He was a finalist in the 2019 Neue Stimmen (New Voices) competition and has won numerous awards and competitions, including the George London Competition, Sullivan Foundation, Brava! Opera Competition, National Opera Association Vocal Competition and the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions (Gulf Coast Region).

Nathan Berg

Canadian bass-baritone Nathan Berg’s career has spanned a vast repertoire on the concert and operatic stage.

Initially, he built a solid reputation in major Mozart roles, while establishing his name as an outstanding interpreter of Baroque and pre-Classical music.

More recently, he has established himself as a Wagner specialist, singing the Dutchman (Der fliegende Holländer), Alberich (Das Rheinghold and Seigfried), and Kurwenal (Tristan und Isolde), and making his role debut as Wotan (Das Rheingold) with the Badisches Staatstheater Karlsruhe in 2018.

Since then he has returned to Theater Basel to sing Wotan/The Wanderer in a complete Ring cycle (2023–25).

This season he has also sung Claudius in Hamlet (Opéra de Montréal) and Filippo in a semi-staged production of Don Carlo (Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra), and in February he was the soloist in Belshazzar’s Feast (Atlanta Symphony Orchestra). Highlights of 2024 included Count Capulet in Roméo et Juliette (Metropolitan Opera) and Alcide in Alceste with Les Epopées in Paris and Vienna, as well as the title role in Bluebeard’s Castle (Boston Symphony Orchestra) and Pater Profundus in Mahler’s Eighth Symphony (NDR Symphony Orchestra at the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg). Other recent stage highlights have included his Metropolitan Opera debut as The Father in the New York premiere of Matthew Aucoin’s Eurydice and an acclaimed house debut with Theater Basel in the title role of Messiaen’s Saint François d’Assise.

A powerful presence on the concert stage, he has appeared with orchestras worldwide and his symphonic repertoire includes Handel’s Messiah, Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and Ninth Symphony, Bach’s Mass in B minor, Vaughan Williams’s Dona Nobis Pacem, Glanert’s Requiem für Hieronymus Bosch, Lutosławski’s Espace du Sommeil, Berlioz’s Lélio, and The Bells by Rachmaninoff, which he performed with the SLSO in 2018.

His award-winning discography includes recordings with Les Arts Florissants, video recordings of Les Indes galantes (Opéra de Paris) and Armide (Théâtre des Champs-Elysées), Dvořák’s Stabat Mater (Atlanta Symphony Orchestra), La Cenerentola (Glyndebourne), and more recently, the role of the Doctor in Wozzeck (Houston Symphony), Dvořák’s Requiem (Royal Flemish Philharmonic), and Beethoven’s Ninth (San Francisco Symphony). Born in Saskatchewan, Nathan Berg studied in Canada, the US, and Paris, as well as at the Guildhall School of Music, London, where he won the Gold Medal for Singers.

Erin Freeman

A versatile and engaging artist, conductor Erin Freeman has served as the Director of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus since the beginning of the 2024/25 season. She also maintains an international presence through multiple positions and guest conducting engagements. She is Artistic Director of the City Choir of Washington and Wintergreen Music, Resident Conductor of the Richmond Ballet, and Director of Choral Activities at George Washington University.

She recently concluded successful tenures as Director of the award-winning Richmond Symphony Chorus and Director of Choral Activities at Virginia Commonwealth University.

In addition to directing the St. Louis Symphony Chorus, most recently preparing performances of Mozart’s Requiem, recent guest conducting engagements have included Washington Ballet, Richmond Ballet (Carmina Burana for her debut at Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts), and her New York City Ballet debut (George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker); the Toledo, Detroit, Portland (Maine), and Virginia symphony orchestras; Charlottesville Symphony; Buffalo and Savannah philharmonic orchestras; and Berkshire Choral International. In 2023/24, she also made debut appearances at Cadogan Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Vienna Musikverein, and conducted four performances with the City Choir of Washington and three productions with the Richmond Ballet.

She has also conducted at Carnegie Hall, Boston Symphony Hall, La Madeleine in Paris, and the Kennedy Center, and has led and/or prepared the Richmond Symphony Chorus for multiple recordings, including the 2019 Grammy-nominated release of Children of Adam by Mason Bates.

A recent finalist for Performance Today’s Classical Woman of the Year, Erin Freeman has also been named one of Virginia Lawyers Weekly’s 50 Most Influential Women in Virginia. She holds degrees from Northwestern University (BMus), Boston University (MM), and Peabody Conservatory (DMA).

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.