Beethoven’s Seventh (November 29-30, 2025)

Program

November 29-30, 2025

- Kevin John Edusei, conductor

- Joyce Yang, piano

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

- Dance Suite, Sz. 77

- Moderato –

- Allegro molto –

- Allegro vivace –

- Molto tranquillo –

- Comodo –

- Finale (Allegro)

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

- Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

Joyce Yang, piano

Intermission

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

- Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92

- Poco sostenuto – Vivace

- Allegretto

- Presto – Assai meno presto

- Allegro con brio

Energy and Reverie

Each work on this program is sophisticated in its design. Bartók’s Dance Suite pours its folk-inspired material into new symmetrical constructions. Rachmaninoff cleverly overlays the traditional theme and variations form over a framework that can be heard as a four-movement concerto, while giving the impression of a fluid and spontaneous “rhapsody.” The “untamed” surface of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony sits on Classical foundations.

But in each case, the sheer energy of the music transcends the architecture, and that energy comes from rhythm. Béla Bartók’s Dance Suite sets things in motion with a thudding tenor drum. Years spent collecting folk music from the villages of Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia yield fruit in the form of irresistible, off- kilter rhythms.

Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini has the energy of a virtuoso showpiece, written for its composer to play. (He performed it here in 1934 to rapturous response.) But in this program, the “Rach–Pag” also brings a sublime moment of reverie: the impassioned 18th variation, which has taken on a life of its own.

Beethoven’s Seventh has its own standalone moment: the hypnotic Allegretto second movement, which was encored (straight away!) at the premiere in 1813 and often performed by itself well into the 20th century. But this symphony that Richard Wagner called “the apotheosis of the dance” brings the program full circle. Beethoven’s obsession with rhythm made him seem mad to his contemporaries, but it’s what gives the Seventh Symphony its dance-like character and visceral appeal.

Of all the elements of music, the one that is fundamental— which affects us most directly—is rhythm. Given the right rhythms, we can dance, or we can dream. And in this concert, rhythm comes to the fore, prompting the question: does Powell Hall have enough room in the aisles?

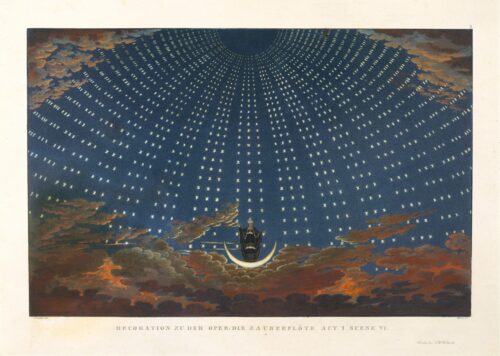

Dance Suite

Béla Bartók

Born 1881, Nagyszentmiklós, Hungary

Died 1945, New York City

Béla Bartók was one of the great composers of the 20th century and also a pioneering ethnomusicologist. During the early years of the last century, he carried a gramophone recorder through rural parts of Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, Turkey, and North Africa, recording thousands of folk melodies. The transcriptions and annotations of those tunes fill more than a dozen large volumes and his books and articles remain the authoritative discussions of this music.

The folk songs and dance tunes Bartók knew and loved so well became the raw materials for his own musical invention. In addition to his many arrangements of authentic folk melodies, Bartók composed a number of works that employ rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic features of ethnic music but are nevertheless original compositions. The most successful of these is his Dance Suite for orchestra. Bartók composed the suite in 1923 for a celebratory concert honoring the 50th anniversary of the unification of the cities Buda, Óbuda (literally “old Buda”) and Pest on opposite banks of the Danube to create the Hungarian capital, Budapest. The music was enthusiastically received at that time, giving Bartók his first major success as a composer.

The Dance Suite comprises five distinct movements, which Bartók ties together with a ritornello, or recurring theme that appears between each of them except the third and fourth. (The same structural device is used by Modest Mussorgsky through the Promenades in his Pictures at an Exhibition, a work Bartók undoubtedly knew.) The suite presents a mingling of different musical cultures. Melodies of Arabic character appear in its first and fourth movements; Magyar, or Hungarian peasant-style, music marks the fourth. The lively third movement mixes Hungarian, Romanian, and Arab idioms. And the ritornello, introduced by muted violins over a drone accompaniment late in the opening movement, also evokes the folk music of Hungary’s Magyar population. But the fiercely energetic finale, Bartók told his publisher, “is so elemental that one can only say that it is of a primitive peasant character and cannot be classified as to nationality.” It is, in other words, pan-ethnic, music that synthesizes the rhythms and melodic styles indigenous to an entire multinational region.

Abridged from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2013

| First performances | November 19, 1923, Ernő Dohnányi conducting the Budapest Philharmonic Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | December 22, 1955, Georg Solti conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 20, 2013, Hannu Lintu conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (doubling piccolos), 2 oboes (one doubling English horn), 2 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, celeste, strings |

| Approximate duration | 17 minutes |

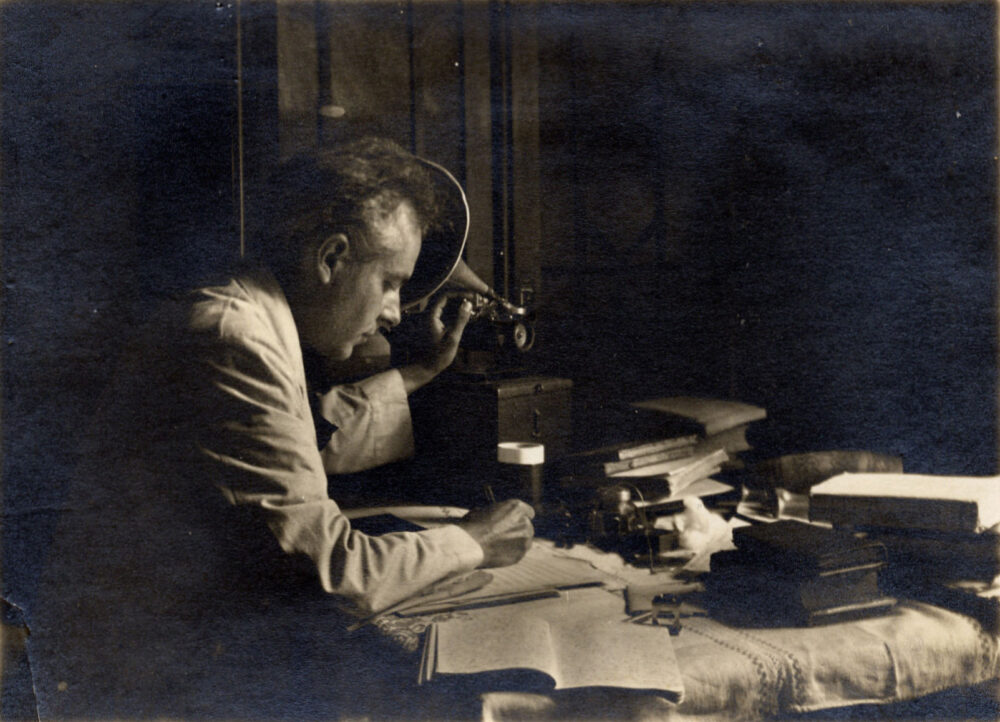

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Born 1873, Semyonovo, Russia

Died 1943, Beverly Hills, California

In 1937, Rachmaninoff approached the Ballets Russes choreographer Michel Fokine with a scenario based on his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini: “Why not recreate the legend of Paganini selling his soul to the Evil Spirit for perfection in art and also for a woman?” He set out in detail how the different sections of the music might represent the 19th-century virtuoso violinist, the diabolical contract, the love episodes, and the triumph of good over evil.

The scenario may have come to Rachmaninoff after he’d composed the music but, more than any other work based on Niccolò Paganini’s theme (and there are many), the Rhapsody has all the signs of being “about Paganini” and not simply a musical exploration of his famous 24th Caprice for solo violin.

The Rhapsody, his final work for piano and orchestra, was completed in August 1934—after Rachmaninoff had settled in the West and turned his focus to a career as a concert pianist. Before the year was out, he’d introduced it to America, creating “a furore” in Baltimore and Washington and being recalled to the platform again and again in St. Louis. An instant success, it has remained one of Rachmaninoff’s most popular creations— admired by audiences and musicians for its lyrical appeal, energy, and satisfying showmanship.

This is the kind of piece that confounds expectations. You can see a piano in front of the orchestra, but it’s not a piano concerto. Rachmaninoff eventually settled on the name “Rhapsody,” but it’s actually a set of variations. And yet, the music does have the character of a freely unfolding rhapsody and—when you take a step back—those variations seem to be grouped, creating the structure of a concerto in several “movements.”

Strikingly, the Rhapsody begins with a short introduction followed by the first variation—a harmonic skeleton in which the piano is silent. Only after this do the violins present Paganini’s theme, accompanied by the soloist. What follows is the quick “first movement” (variations 2–10) concluding with an ethereal cadenza for the soloist (variation 11) that transitions into an artful minuet and scherzo (variations 12–15). At variation 16, the music returns to two-four time for the “slow movement,” culminating in the best-known moment, the inspired variation 18.

What Tune is That?

The 18th variation from the Rhapsody has become one of Rachmaninoff’s most famous melodies. It has turned up in movies such as Groundhog Day (1993) where Bill Murray learns to play it; the 1995 remake of Sabrina; Dead Again (1991); Somewhere in Time (1980); Rhapsody (1954); and, more recently, in the sixth season of The Good Wife (2015).

According to the pianist Vladimir Horowitz, Rachmaninoff said of variation 18, “This one is for my manager.” It’s an ingenious invention: a dreamy and impassioned tune created by turning Paganini’s lively, jumping theme upside down. (The composer’s sketchbooks in Moscow indicate that this inversion was one of the first ideas Rachmaninoff had for the Rhapsody.)

Equally ingenious in the Rhapsody is the way Rachmaninoff weaves in quotations of the Dies irae plainchant for the dead, beginning with variation 7, where it’s outlined by the soloist with sparse chords. These become the musical allusions to the “Evil Spirit.” Variations 19–24 provide a spirited finale, with one final quotation of the Dies irae by the full brass section.

Yvonne Frindle © 2022/2025

| First performance | November 7, 1934, in Baltimore, Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra, with the composer as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | December 14, 1934, Vladimir Golschmann conducting, with the composer as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | November 27, 2022, Xian Zhang conducting, with George Li as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 24 minutes |

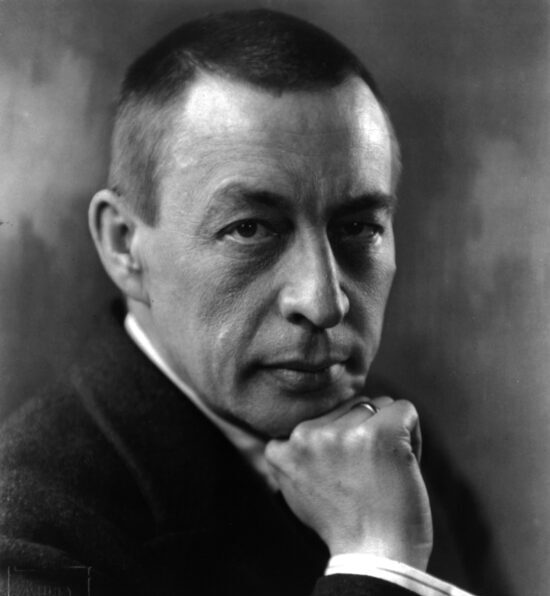

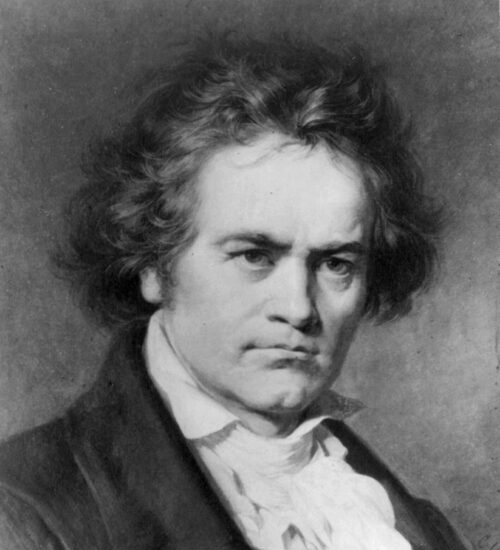

Seventh Symphony

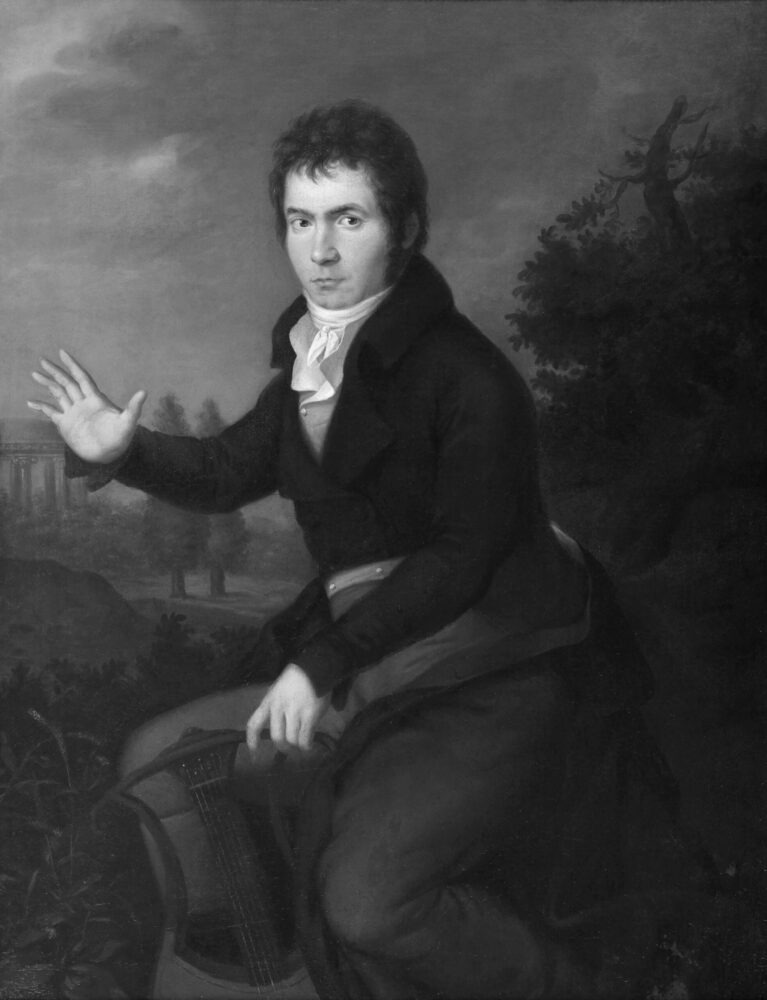

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died 1827, Vienna, Austria

Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony was first performed in December 1813 in an atmosphere of triumph and euphoria: Napoleon’s imperial ambitions had been squashed; the composer’s popularity was at its height. The symphony had been completed in 1812, so its joyous spirit had nothing to do with military victory, but audiences heard in it the enthusiastic mood of the “battle symphony” that Beethoven had composed for the occasion. One critic even described the Seventh as a “companion piece” to Wellington’s Victory. Regardless, the Seventh Symphony made an impression in its own right, and the assistant concertmaster, Louis Spohr, noted that the “wonderful second movement had to be repeated.”

The key to the symphony’s direct appeal—then and now—lies in a single musical element: rhythm. Never before had rhythm been given such a fundamental role in Beethoven’s music. It generates the symphony’s structure, its melodic and harmonic gestures, and ultimately its powerful rhetoric. But unlike the Fifth Symphony, where the famous opening rhythmic motif is developed, fragmented, and expanded, the Seventh Symphony adopts a strategy of obsessive repetition of rhythmic patterns.

After an imposing slow introduction (Poco sostenuto)—almost a movement in itself—Beethoven spins his first main theme from a skipping rhythm on a single note. At least, most listeners today will likely hear it as a “skipping rhythm,” agreeing with Wagner’s description of the symphony as the “apotheosis of the dance.” The experience of Beethoven’s Seventh is a kinetic one.

But Beethoven’s 19th-century listeners would also have recognized in that rhythm the dactylic meter of classical Greek poetry. (Imagine the word “Amsterdam” repeated over and over.) Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny, noting the extensive use of poetic meters, concluded that Beethoven “was thinking about the forms of heroic poetry and must have deliberately turned toward the same in his musical epic.” Others of Beethoven’s generation also interpreted the use of poetic meter as a deliberate evocation of ancient Greek music and poetry. A.B. Marx, for example, described the massive opening of the first movement as “the kind of invocation with which we are particularly familiar in epic poets,” and the finale as a “Bacchic ecstasy.” This last interpretation was given the seal of approval by Wagner.

Beethoven himself is silent on the Seventh Symphony. We don’t know whether he was trying to evoke the ancient world or not, but such an aim would have been in keeping with the ideals of Romanticism, which sought to fuse of the Modern and the Antique. Nowhere is this more strikingly conveyed than in the hypnotic second movement, “the menacing chorus of ancient tragedy.” Its point of departure—and its point of return—is uncertainty, with harmonically unstable chords that draw us into the music. Beethoven adopts the simplest of means: the throbbing tread of an austerely repeated pattern (ostinato) and the piling on of more instruments and transforming woodwind color for ever-increasing intensity. (It’s easy to hear why this quietly spectacular movement was encored at the premiere.)

The dazzling scherzo (Presto) shows Beethoven at play: setting his basic rhythms against each other and creating ambiguity within a relentless pulse. In the trio sections, the repeated notes join to create a sustained figure, more expansive and lyrical but equally insistent.

For his finale (Allegro con brio), Beethoven compresses the contrasts of the first movement into the opening bars: two explosive gestures unleash whirling figurations above unremitting off-beat rhythms in the bass. Once more he spins a web of interlocking rhythms, ensnaring us in what his contemporaries described as “absurd, untamed music” and a “delirium.” As Beethoven himself claimed: “Music is the wine which inspires us to new acts of generation, and I am Bacchus who presses out this glorious wine to make mankind spiritually drunk.”

On its surface, this symphony conforms to classical structure, but underneath the equilibrium of a four-movement symphony Beethoven creates a feeling of spontaneity, motion, vitality (Apollo versus Bacchus, if you like.) The introspective moments of the introduction, the central part of the scherzo, and the second movement simply highlight the irrepressible brilliance of the symphony as a whole. Whether we attribute its magic to Terpsichore, the muse of the dance, or to Clio, the muse of epic poetry, Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony is an inspired invention.

Abridged from a note by Yvonne Frindle © 2004/2025

| First performance | December 8, 1813, in Vienna, the composer conducting |

| First SLSO performance | December 3, 1908, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 15, 2021, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, strings |

| Approximate duration | 40 minutes |

Artists

Kevin John Edusei

In the 2025/26 season, German conductor Kevin John Edusei is the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra’s Conductor-in-Residence. He was previously Chief Conductor of the Munich Symphony Orchestra (2013–2022) and Bern Opera House (2015–2019).

In addition to his St. Louis Symphony Orchestra debut, this season he also makes his Atlanta Symphony Orchestra debut, and returns to the Kansas City, Colorado, Indianapolis, and Seattle symphony orchestras. Internationally, he returns to the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Radio Philharmonie, and Royal Scottish National Orchestra, and makes debut appearances with the Prague Symphony Orchestra and Orquesta Sinfónica de Castilla y León.

Recent guest conducting highlights include an acclaimed New York Philharmonic debut and his Asian debut with the Taiwan Philharmonic, as well as concerts with the Los Angeles, London, Netherlands Radio, and Munich philharmonic orchestras, Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra, and Berlin Konzerthaus Orchestra.

In 2022, he made his Royal Ballet and Opera debut conducting La bohème, returning for Madama Butterfly. He has also conducted for Semperoper Dresden, English National Opera, Hamburg State Opera, Volksoper Wien, and Komische Oper Berlin. During his tenure in Bern, he conducted Peter Grimes, Salome, Bluebeard’s Castle, Kátya Kábanová, Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde, and Mozart’s Da Ponte operas.

Kevin John Edusei studied conducting at the University of the Arts Berlin and the Royal Conservatory of The Hague.

Joyce Yang

Joyce Yang came to international attention in 2005 when she won the silver medal at the 12th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The following year she made her New York Philharmonic debut and toured with the orchestra to Asia, making a triumphant return to her hometown of Seoul, South Korea.

Since then, Yang has showcased her colorful musical personality in recitals and collaborations with the world’s top orchestras and chamber musicians. Notable engagements include the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, and the Toronto, Vancouver, Sydney, Melbourne, and New Zealand symphony orchestras, as well as a Rachmaninoff cycle with Edo de Waart and the Milwaukee Symphony. Earlier this year, she returned to the Aspen Music Festival performing Brahms, and made her San Diego Mainly Mozart festival debut.

Yang has given innovative recitals at the Lincoln Center, Metropolitan Museum, Kennedy Center, Chicago’s Symphony Hall, Zurich’s Tonhalle, and for Musica Viva Australia, as well as performing with the Takács, Emerson, and Alexander string quartets. A champion of new music, she has premiered concertos by Michael Torke, Jonathan Leshnoff, and Reinaldo Moya, and earlier this month, Leshnoff’s Rhapsody on America.

In recent years, Yang has explored the relationship between music and dance in her role as guest artistic director for the Laguna Beach Music Festival, and with Aspen Santa Fe Ballet in Half/Cut/Split (Schumann’s Carnaval).

Joyce Yang received her first piano lesson at age four; by ten, she had entered the Korea National University of Arts School of Music. In 1997 she moved to the US to study at the Juilliard School, and in 2010 she received an Avery Fisher Career Grant.

Joyce Yang is a Steinway artist.