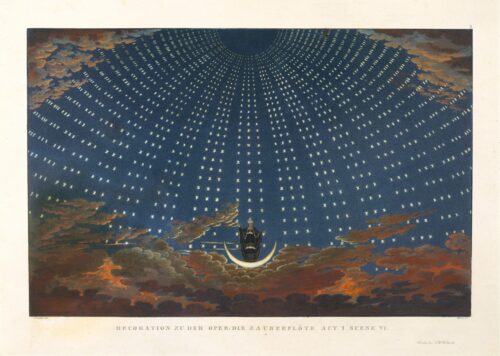

Brahms’ First Symphony (February 21 & 23, 2025)

Program

February 21 & 23, 2025

David Afkham, conductor

Saleem Ashkar, piano

Outi Tarkiainen (b. 1985)

- The Ring of Fire and Love

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

- Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K.491

- Allegro

Larghetto

Allegretto

- Allegro

Saleem Ashkar, piano

Intermission

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

- Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

- Un poco sostenuto – Allegro

- Andante sostenuto

- Un poco Allegretto e grazioso

- Adagio – Più andante – Allegro non troppo,

- ma con brio

Labor of Love

Plenty of artists have likened the creative process to the act of giving birth, but as composer Outi Tarkiainen observes, childbirth is a theme not often addressed in music. Regardless, she finds inspiration in this earth-shattering, love-filled experience. The Ring of Fire and Love seeks commonality between the seismic activity of the Pacific Rim, the corona of a solar eclipse, and childbirth; the emotional range of this ten-minute tone poem is correspondingly vast. The icy beginning is delicate yet fierce, with piccolos and impossibly high violins; muted horns bring an ominous stillness, thudding drums power. The music descends and rises in heartfelt waves. And while the beginning may seem violent, the music finds a vibrant and glowing sonority in its literal “labor of love.”

Mozart’s sublime Piano Concerto No. 24 traverses a similarly vast emotional realm, combining musical hypomania with the feeling of tragedy that 18th-century musicians associated with the key of C minor. Over the course of half an hour, we experience quiet foreboding and stormy violence, despair and resignation, gentle lyricism and brilliant audacity.

There’s an enduring anecdote in which Beethoven, on hearing Mozart’s C-minor concerto, declares to a fellow composer: “We shall never be able to do anything like that!” The story is appealing, but dubious. More reliable is Brahms’s reaction to Beethoven: “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea how it makes one feel to hear the thunderous step of a giant like him always behind you!”

The overwhelming legacy of Beethoven led Brahms to labor over his first symphony for decades. The result was perhaps less a labor of love than one of defiance, although the symphony did contain a gesture of love in the form of a birthday message to his friend Clara Schumann (listen for the big “Alphorn” tune a few minutes into the finale). And it shares with Tarkiainen’s work a sense of trajectory, beginning in a place of turmoil and arriving at a radiant and life-affirming conclusion.

The Ring of Fire and Love

Outi Tarkiainen

Born 1985, Rovaniemi, Finnish Lapland

Outi Tarkiainen was born in Rovaniemi, in Finnish Lapland, far to the north, and much of her music is inspired by the Arctic Circle. “I have a fundamental longing for the northernmost regions within me,” she has said. Another recurring theme is the experience of motherhood, including childbirth, which she connects with other natural phenomena, such as astronomy or geography.

Composed in 2020, The Ring of Fire and Love falls into this sequence of works. Tarkiainen explains:

The Ring of Fire is a volcanic belt that surrounds the Pacific Ocean and in which most of the world’s earthquakes occur. It is also the term referring to the bright ring of sunlight around the moon at the height of a solar eclipse, when the moon covers only the central part of the sun. Yet, the same expression is also used to describe what a woman feels when, as she gives birth, the baby’s head passes through her pelvis. That moment is the most dangerous in the baby’s life, its little skull being subjected to enormous pressure, preparing it for life in a way unlike any other. The Ring of Fire and Love is a work for orchestra about this earth-shattering, creative, cataclysmic moment they travel through together.

This ten-minute tone poem was commissioned by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra and two Finnish orchestras: the Jyväskylä Sinfonia and Kymi Sinfonietta. It was subsequently recorded by the Finnish Radio Symphony and conductor Nicholas Collon, together with Tarkiainen’s Midnight Sun Variations (inspired by the birth of her son), Songs of the Ice, and Milky Ways, an English horn concerto. David Afkham conducted the first US performance in 2023 with the Minnesota Orchestra, and in 2024 The Ring of Fire and Love was nominated for the Music Composition Prize of the Foundation Prince Pierre de Monaco.

Outi Tarkiainen studied composition at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, as well as at the University of Miami and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. Many of her early works from the 2010s were rooted in jazz, during which time she collaborated with European jazz orchestras as a composer and conductor. (At one point in The Ring of Fire and Love she gives the first trumpet a solo “like Miles Davis” with his signature Harmon mute.) More recently, she has been commissioned by the Berlin Philharmonic, several BBC orchestras, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, and Iceland Symphony Orchestra, among others.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

Learn more about Outi Tarkiainen and listen to her music at www.outitarkiainen.fi

| First performance | March 18, 2021, Sakari Oramo conducting Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (doubling piccolos), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 10 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K.491

W.A.

Mozart

Born 1756, Salzburg, Austria

Died 1791, Vienna, Austria

Mozart was so busy between October 1785 and April 1786 that he didn’t even have time to write letters home. Even by his own standards he completed a huge number of major works: a violin sonata, several pieces for the Masonic Lodge of which he was a member, various “insert” pieces for other operas, works for wind ensembles, a “musical comedy” Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario), three piano concertos, and his opera The Marriage of Figaro.

This period also marked the end, for a time, of Mozart’s prominence as a soloist. He gave his annual “academy” concert—probably featuring this concerto—on April 7 in Vienna’s Burgtheater, but, unusually for him, he did not plan a series of subscription concerts for the season of Lent as he had in previous years. This spawned a number of more or less fanciful theories in the decades that followed, especially given the nature of the C minor concerto. One is the old myth about his falling from favor with his public—the concerto’s uncompromising nature was supposedly not to Viennese taste. Another, more curious, is the notion that Mozart’s hands were damaged: it was said, by Karl Beethoven for one, that Mozart’s fingers were so bent from constant playing that he was unable to use a knife at table. (It’s true that rheumatic fever, from which Mozart suffered on occasion, can cause arthritis, but as Mozart biographer Maynard Solomon points out, the “fine calligraphy” of Mozart’s scores, not to mention his excellence at billiards, make this hard to believe.)

Politically, things were strained in Vienna. Emperor Joseph II was determined to modernize his realm, curtailing the power of the church and nobility (for which reason he supported Mozart’s proposal to make Figaro into an opera), reforming the legal system, and offering a greater degree of liberty than his predecessor. But his reforms were inconsistent. He’d recently passed the Freemasonry Act in order to monitor its members’ activities, and in early 1786, his intervention in a murder case led to a gruesome public execution that drew thousands to the streets not far from Mozart’s home.

To what extent might all this bear on the concerto? It is unique in Mozart’s output in several ways: it uses a large orchestra for a vast range of effects; it avoids virtuosic display for its own sake; its first movement is in triple time (a meter with four beats to the measure was customary); the opening theme, characterised by downward steps followed by wide upward leaps, is broken into progressively smaller units by short, gasping silences. The turbulence this creates prefigures Beethoven and has led commentators ever since to describe the piece as “tragic” or “demonic.”

Solomon has noted that in the slow movement, as in other works of this time, Mozart summons up “every gradation of emotion—from terror to vague feelings of unease, from unbearable intense pleasures bordering on ecstasy to a floating placidity and contentment.” And again, in the finale Mozart uses a form beloved of Beethoven and puts his theme through a set of eight variations, exploring a wide range of emotional worlds in the process.

The other factor in the equation is Figaro, of whose importance (both musically and politically) Mozart was well aware. Whether the turmoil and glimpses of beatific peace in this work are the result of Mozart’s response to his circumstances and the times will remain an open question. We can however point out that this work issues from the composer who was in the process of revolutionizing the way in which human emotions and relationships could be depicted in music.

Abridged from a note by Gordon Kerry © 2002

| First performance | Mozart entered this concerto in his thematic catalog on March 24, 1786, and may have given its first performance in Vienna on April 7 that year |

| First SLSO performance | March 9, 1951, with Vladimir Golschmann conducting and Gaby Casadesus as guest soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 20, 2010, with André Previn conducting from the piano; in 2019 the SLSO recorded the concerto with David Robertson and soloist Orli Shaham |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; flute, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 31 minutes |

Symphony No. 1

Johannes Brahms

Born 1833, Hamburg, Germany

Died 1897, Vienna, Austria

This symphony begins with an afterthought—a powerful slow introduction devised years after Brahms had conceived the main part of the first movement. The whole symphony took more than 14 years to write, and by the time he’d completed it in 1876, Brahms was 43 years old. Beethoven, by comparison, was 30 when he composed his first symphony, Mozart not even 10.

The First Symphony was not Brahms’s first essay in orchestral writing, or even his first attempt at a symphony. Both honors go to his First Piano Concerto (1855), which began life as a symphony in D minor. Brahms had been goaded into symphonic ambitions by Robert Schumann’s famous 1853 article “New Paths,” which hailed him in almost messianic terms as “the One who has been called”—a second Beethoven who would be the savior of the symphony, a genre in decline.

The article was a mixed blessing for Brahms. It drew attention to his talent while inviting ridicule from those who believed there was nothing more to be done with the symphony that Beethoven had not already achieved. Brahms was especially conscious of Beethoven’s legacy: “I shall never write a symphony! You have no idea how it makes one feel to hear the thunderous step of a giant like him always behind you!”

Beethoven’s stature in 19th-century Europe was overwhelming; the challenge left by his Ninth Symphony, with its unprecedented vocal finale, insurmountable. No wonder Brahms spent nearly 20 years procrastinating: he completed that piano concerto, two orchestral serenades on a symphonic scale, and the brilliant Variations on a Theme of Haydn rather than commit to an actual symphony. But from a crucible fueled by rejected drafts and discarded sketches, there eventually emerged a symphony that was extraordinary, not in its innovation but in its ingenuity and power of expression.

In 1862 Brahms sent Clara Schumann, one of his most trusted friends, a draft of the first movement. Without its slow introduction (Un poco sostenuto) the impetuous opening of the Allegro must have been startling, and Clara wrote to the violinist Joseph Joachim remarking on its harshness.

What Brahms added later is a more subdued prelude to the immense tragedy of the first movement. The throbbing timpani notes of the opening hint at the struggle to come as the symphony follows a trajectory that mirrors both Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (beginning in fateful C minor and ending in radiant C major) and his Ninth (D minor to D major). The momentum and sense of dramatic conflict is then confirmed by first movement’s stormy Allegro. But for all its romantic turbulence, the symphony never departs from classical principles of structure, nor does it exceed the boundaries of the harmonic system inherited from Beethoven.

The monumental weightiness of the first movement is what Brahms’s listeners would have expected of a symphony. By contrast, the lighter central movements—one not quite a slow movement, the other not quite a scherzo—sound as if they’d be more at home in one of Brahms’s serenades, especially when the concertmaster is given a solo at the conclusion of the second movement (Andante sostenuto).

There are no true scherzos in Brahms’s symphonies—the closest he comes is the boisterous third movement of his Fourth Symphony. For the third movement of the First (Un poco Allegretto e grazioso) he retains the scherzo’s dance structure with its contrasting central trio section, but forgoes the traditional whirlwind exuberance for music that’s gentle and folk-like.

The first three movements were completed and apologetically circulated to friends and colleagues for their appraisal. By 1868, work on the final movement was underway, and the horn theme from its Più Andante section became a birthday greeting for Clara, an “Alphorn” tune set with the words: “High on the mountain, deep in the valley, I greet you many thousands of times!”

The finale would have given Brahms the most trouble, for it was in its finale that Beethoven’s Ninth “trespassed over music’s boundaries” (Hans von Bülow), introducing voices, and therefore text, into what was meant to be a wordless, absolute medium. Other composers had since grappled with the idea of a symphony with voices—Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang (Hymn of Praise) was a “symphony-cantata,” Berlioz had extended the concept still further with his Roméo et Juliette, a “dramatic symphony.” But Brahms returns to a purely instrumental solution for his symphonic finale, and in doing so confronts the legacy of Beethoven head on.

As in the first movement, there is a portentous slow introduction (Adagio – Più Andante)—a “magnificent cloudy procession” of themes that will take full shape in the main section. Brahms’s passionate yet introverted voice emerges time and again in his tempo directions, full of qualifications, and the finale is no exception: Allegro non troppo, ma con brio (Fast, not too much, but with life). At this point Brahms makes an allusion—now famous—to Beethoven’s Ninth with a noble theme in the strings, broad and square. From the outset, listeners remarked on its similarity to the “Ode to Joy”; Brahms’s retort became “Yes indeed, and what is more remarkable is that every fool hears it immediately.”

Fools or not, the similarity we hear is almost as immediately abandoned. The allusion is not a sign of Brahms’s inability to escape the influence of Beethoven, as some of his contemporaries thought, but his means of both embracing and distancing himself from the “giant.” And it is the Alphorn tune rather than a Brahmsian “Ode to Joy” that becomes the climax of the movement and the work as Brahms turns around to face the “giant” with a magnificent finale that celebrates the symphonic possibilities of the orchestra.

Yvonne Frindle © 2000/2025

| First performance | November 4, 1876, in Karlsruhe, Germany, conducted by Otto Dessoff |

| First SLSO performance | February 18, 1910, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | January 8, 2022, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 45 minutes |

Artists

David Afkham

German conductor David Afkham makes his SLSO debut this week in a season that also includes debuts with the Berlin and Finnish radio symphony orchestras and the Bruckner Orchester Linz. In 2024/25 he also returns to the Chicago and Seattle symphony orchestras, Stuttgart State Orchestra, and Orchestre National de Lyon. He has held the post of Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of the National Orchestra and Choir of Spain since 2019.

His career has been marked by a series of critically acclaimed performances, conducting leading orchestras such as the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, Staatskapelle Berlin, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Staatskapelle Dresden, Wiener Symphoniker, Orchestre National de France, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Oslo Philharmonic, Orchestra of the National Academy of Santa Cecilia, and the Southwest German (SWR), Bavarian, Frankfurt, and Swedish radio symphony orchestras, as well as the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, and Mahler Chamber Orchestra. In the US, he has conducted the Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Minnesota orchestras, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Pittsburgh and Chicago symphony orchestras, the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Tanglewood), and the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra (New York).

Opera highlights include Arabella (Dresden and Madrid), Hänsel und Gretel (Frankfurt), The Flying Dutchman (Stuttgart), and Ginastera’s Bomarzo (Madrid). He has also conducted La traviata at the Glyndebourne Festival and on tour, as well as semi-staged projects for the National Orchestra and Choir of Spain, including Tristan und Isolde, Elektra, Salome, and Bluebeard’s Castle. This season he returns to Semperoper Dresden to conduct Fidelio.

David Afkham studied piano, music theory, and conducting in Freiburg, before continuing his studies at the University of Music “Franz Liszt” Weimar. He was the first recipient of the Bernard Haitink Fund for Young Talent and assisted Haitink on several major projects, including symphonic cycles with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and the Chicago and London symphony orchestras. He was also Assistant Conductor of the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra (2009–12). In 2008 he won the Donatella Flick Conducting Competition in London, and in 2010 he was the inaugural recipient of the Nestlé and Salzburg Festival Young Conductors Award.

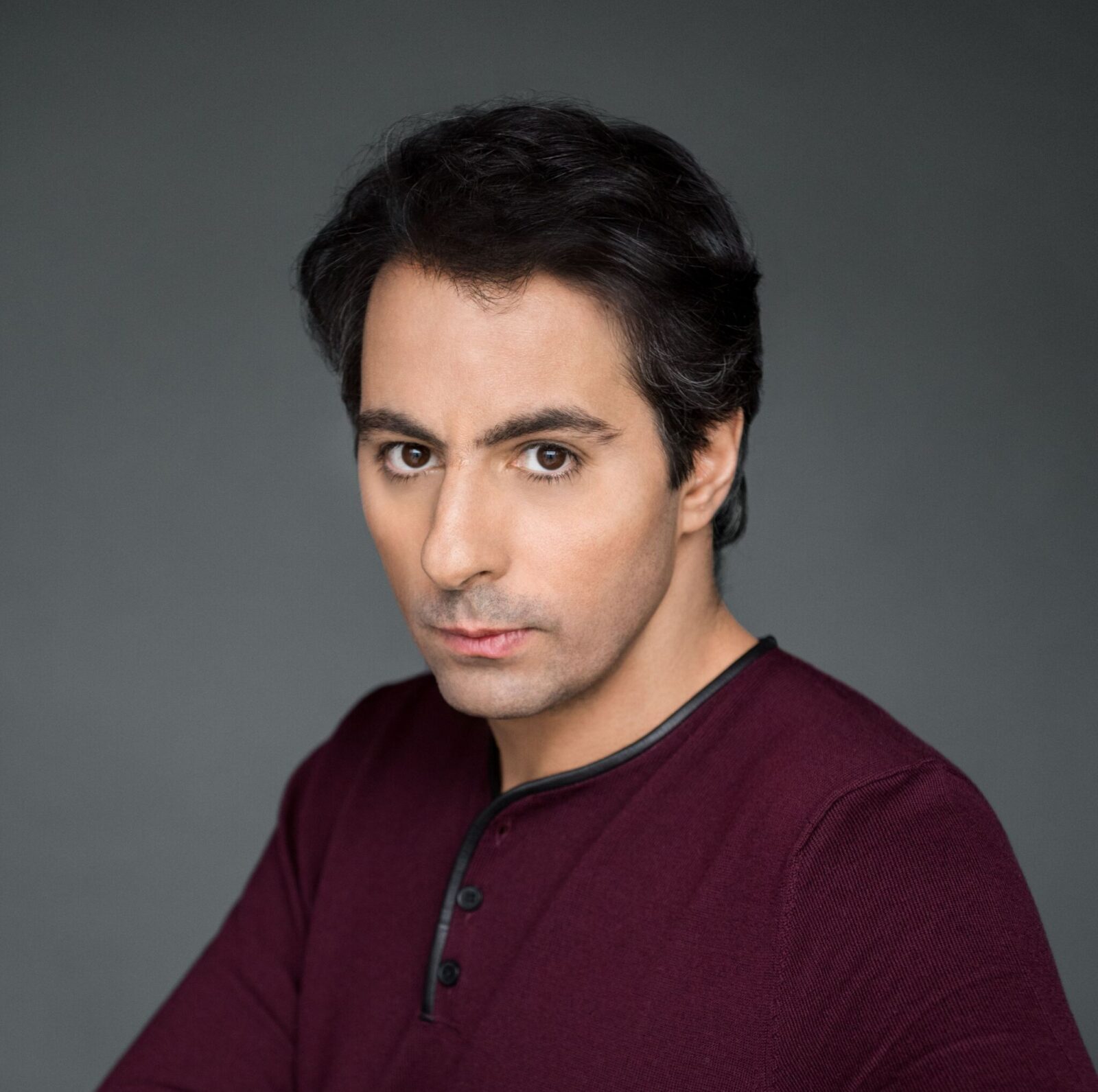

Saleem Ashkar

Saleem Ashkar returns to St. Louis, having made his SLSO debut in January 2020 playing Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with conductor Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider. Since making his Carnegie Hall debut at 22, he has established an exciting international career. This season also sees him return to Orchestre National de Lyon with Szeps-Znaider and Württembergische Philharmonie Reutlingen with Ariane Matiakh, as well as his Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra debut, and he will present the first of a two-part Schumann recital cycle at Queen’s Hall in Copenhagen.

Recent concerto highlights have included the Bamberg Symphony, Gävle Symphony Orchestra, Valencia Orchestra, Konzerthausorchester Berlin, Brussels Philharmonic, Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, and Copenhagen Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2021, he toured Germany with the Kammerakademie Potsdam performing Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and the premiere of David Coleman’s Piano Concerto.

He has a close relationship with many leading conductors, including Daniel Barenboim, Riccardo Chailly, Jakub Hrůša, Pietari Inkinen, Fabio Luisi, Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti, and Kazushi Ono, and previous seasons have seen him perform with the Vienna Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, and the Detroit, Vancouver, and Tokyo Metropolitan symphony orchestras, as well as a three-week Australian tour.

As a recitalist and chamber musician, he has a reputation as a Beethoven specialist, performing complete sonata cycles in Prague, Duisburg, and Berlin. He has also recorded the complete Beethoven sonatas, releasing the final volume in 2023. Previous recordings include Mendelssohn’s piano concertos (Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and Chailly) and Beethoven’s concertos No. 1 and No. 4 (NDR Elbphilharmonie and Ivor Bolton).

He is Artistic Director of the Galilee Chamber Orchestra, bringing together young and professional musicians to foster collaboration between the Arab and Jewish communities in Israel. In 2022 they made their first North American tour, performing at Carnegie Hall with Joshua Bell as soloist and Koerner Hall, Toronto; this season they return to Europe, with concerts at the Bachfest Leipzig, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, and Madrid.

Born in Nazareth, Saleem Ashkar studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London and the University of Music and Theater in Hanover, Germany. He is currently a professor of piano and director of the keyboard program at Brown University.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.