Brahms’ Violin Concerto (April 11-13, 2025)

Program

April 11-13, 2025

John Storgårds, conductor

Francesca Dego, violin

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

- Violin Concerto

- Allegro non troppo

- Adagio

- Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace

Francesca Dego, violin

Intermission

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

- Lemminkäinen Suite (Four Legends from the Kalevala), Op. 22

- Lemminkäinen and the Maidens on the Island

- The Swan of Tuonela

- Lemminkäinen in Tuonela

- Lemminkäinen’s Return

Friendship and Heroism

The last time the SLSO performed Johannes Brahms’s Violin Concerto, in 2017, it was programmed after intermission in “symphony spot.” This is not uncommon—the concerto is long, at nearly 40 minutes, and it has a serious, symphonic heft. Jean Sibelius, himself a violinist, would later describe it as almost “too symphonic” in its conception. Its first soloist, Joseph Joachim, when programming the premiere, also thought it belonged at the end of the concert—with the Beethoven violin concerto to begin! Brahms, however, disagreed: “Beethoven shouldn’t come before mine…perhaps the other way around.”

For this program, Finnish conductor John Storgårds has chosen to program the concerto in its customary place, sending us into intermission with its toe-tapping rondo theme—a nod to Brahms and Joachim’s shared enthusiasm for Hungarian dance music. And it promises to be an exciting first half, with the SLSO debut of violinist Francesca Dego.

We return for a work that’s a symphony in all but name: Sibelius’s Lemminkäinen Suite or, as Sibelius soon came to think of it, four “legends” inspired by Finnish epic poetry. Traditionally, a suite offers music from the ballroom or the theater, but in its shape and scope this four-movement suite could easily pass for a symphony, and when he was an old man, Sibelius said as much.

This concert unites music born of deep affection and friendship (Brahms) and a work of heroic adventure (Sibelius). Each piece, in its own way, is a work of vision and powerful imagination. But there’s a play of opposites, too. Brahms was always a little diffident and self-deprecating about his work; the Sibelius of Lemminkäinen, on the other hand, was a young man at the vanguard of a new national music, and his music conveys a thrilling optimism.

Violin Concerto

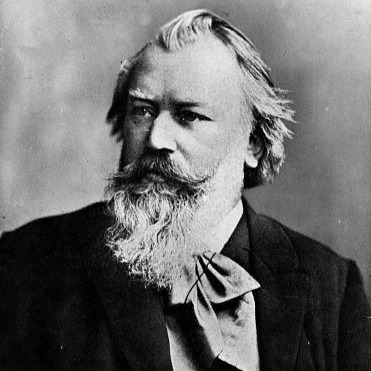

Johannes Brahms

Born May 7, 1833, Hamburg

Died April 3, 1897, Vienna

Of the many contradictions that marked Brahms’s personality, none seems more significant to the development of his music than his simultaneous need for solitude and, on the other hand, the affection, admiration, and stimulation provided by a devoted circle of friends. He was withdrawn and often rude toward those who tried to befriend him. He never married and lived alone for most of his adult life. But he also maintained close relationships with a number of sympathetic individuals. Most of these were musicians: Clara Schumann, widow of the composer Robert Schumann and one of the great pianists of the 19th century; Theodor Billroth, an eminent surgeon, violist, and pianist, whose artistic judgment Brahms valued highly; Elisabeth von Herzogenburg, a talented and highly cultured amateur performer and composer; and not least, the great violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms’s oldest friend.

Joachim was by any standard an extraordinary musician. A virtuoso of the first rank, he nevertheless disdained the showy pyrotechnics of such famous 19th-century violinists as Paganini, Wieniawski, and Sarasate, preferring instead to devote himself to interpretations of the classical repertoire. His own compositions were greatly admired by his contemporaries.

Brahms was an obscure young pianist and fledgling composer when he first met Joachim in 1853, but the latter quickly recognized the enormity of his gift.

“I have never come across a talent like his before,” Joachim wrote at the time. “He is miles ahead of me.” Before long, the two had established a firm friendship. Their relationship, though not always smooth, endured some 44 years until Brahms’s death in 1897.

The friendship between Brahms and Joachim produced a number of tangible results, the greatest coming in 1878. In August of that year, Brahms, who habitually understated his creative efforts, wrote to Joachim that he was sending “a few violin passages” to try out. These “passages” proved to be the first movement and part of the finale to a concerto he had sketched during the summer. Joachim responded enthusiastically and encouraged Brahms to proceed.

During the next several months the two corresponded frequently and met several times to try out portions of the concerto as it progressed. Brahms originally planned the work to be in four movements (he would realize this unorthodox concerto format three years later in his Second Piano Concerto), but eventually discarded the two central movements in favor of what he disparaged as a “poor Adagio.” By pressing Brahms to work faster than was his habit, Joachim was able to perform the Violin Concerto for the first time on New Year’s Day 1879, in Leipzig. (That program—a marathon for the soloist—began with Beethoven’s Violin Concerto.)

Brahms repeatedly asked his friend to scrutinize his work, retaining many of his suggestions, and it was Joachim who provided the first-movement cadenza for the premiere. Joachim’s most important influence on the concerto, however, may have been more general and pervasive: in view of the esteem in which Brahms held him and the overall character of the work, it’s not difficult to imagine the piece as an homage to the violinist—a kind of musical portrait.

The first movement (Allegro non troppo) is marked throughout by the blend of unpretentious grandeur and controlled energy established in the long orchestral exposition. Characteristically, Brahms forges each of the themes presented in this passage from several brief interlocking melodies that can expand, develop, and play off each other. The violin in turn amplifies the thematic material already presented by the orchestra and contributes an exceptionally lovely melody of its own.

The “poor Adagio” is obviously and profoundly an expression of great tenderness and affection. Brahms opens with one of his most beautiful and long-breathed melodies. (It is also one of the great oboe solos in the orchestral literature.) And although the music passes across more troubled thoughts in the central portion of the movement, it returns to this initial melodic impulse to recapture the peaceful vein in which it began.

The Hungarian flavor of the finale (Allegro giocoso) is certainly a bow to Joachim, who not only was of Hungarian background but had himself written a “Hungarian Concerto” and dedicated it to Brahms. The recurring principal theme of this rondo-form movement that evokes the distinctive violin style that Joachim knew and Brahms loved so well, but the intervening episodes are equally notable for their energy and bravura passagework.

Abridged from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2004

| First performance | January 1, 1879, Joseph Joachim was the soloist and the composer conducted the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | January 17, 1913, Max Zach conducting, with soloist Efrem Zimbalist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 30, 2017, David Robertson conducting, with soloist Augustin Hadelich |

| Instrumentation | solo violin; 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 38 minutes |

Lemminkäinen Suite

Jean Sibelius

Born 1865, Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

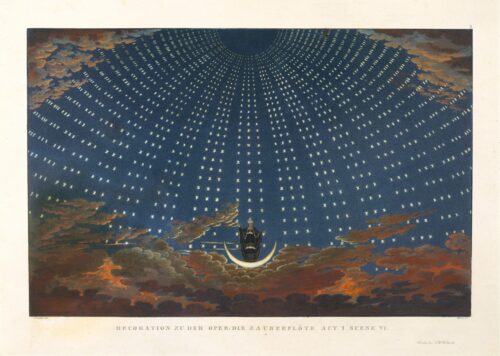

Jean Sibelius’s Lemminkäinen Suite began life in 1893 as the prelude to an opera, The Building of the Boat. The opera was to be the Finnish answer to Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle, and like Wagner, Sibelius found inspiration in mythology, returning to the Kalevala, a 19th-century collection of epic poetry that played a key role in the formation of Finnish national identity.

Sibelius was more influenced by Wagner than he was willing to admit, but he didn’t embrace Wagner’s theory of the all-embracing music drama. His instincts were more closely aligned with those of Wagner’s contemporary Franz Liszt, who as inventor of the symphonic poem, had demonstrated that emotional and expressive content could dictate musical structures. Sibelius soon abandoned his opera, setting out instead to write four “legends,” or symphonic poems, based on scenes from the Kalevala. The prelude from 1893 would become The Swan of Tuonela, the most famous of the four.

Our hero is introduced in the first legend, Lemminkäinen and the Maidens on the Island. Lemminkäinen is a Finnish Don Juan—young, handsome, and extremely reckless. He sails his boat to Saari (literally “island”) when all the men are away and has a very good time, but is forced to flee when the men return. If the music is any guide, the maidens of the island are spirited young women: Sibelius gives them a lively major-key woodwind theme above a rustic drone bass. Meanwhile, Lemminkäinen’s youthful indiscretions are accompanied by ardent and sensuous music. Listen for the ecstatic horn flourishes that wouldn’t be out of place in Richard Strauss’s Rosenkavalier.

The Swan of Tuonela begins with aural magic as Sibelius moves a single chord up through the registers of the orchestra, changing its colors on the way. The shimmering effect in the strings brings to mind the prelude to Wagner’s opera Lohengrin, which has its own swan connection. A little further in, the English horn begins to “sing” in another nod to Wagner, this time the prelude to Act III of Tristan und Isolde, which gives the same lamenting role to the same instrument. Imagine the Swan of Tuonela (the Land of the Dead) floating majestically on a river of black water. The atmosphere is dark and moody, and if you watch the stage, you’ll see that Sibelius leaves out the bright-sounding instruments—flutes, upper clarinets, and trumpets—in his quest for a somber, glassy sound.

After the action of the Maidens on the Island and the ambiance of The Swan of Tuonela, the third legend, Lemminkäinen in Tuonela, introduces a struggle with evil and death. Lemminkäinen has been challenged to kill the Swan in order to win the hand of the Daughter of the Northland—Pohjola’s Daughter. But he’s ambushed and killed alongside the sacred river, and his body is hacked to pieces and thrown into the water. His mother then combs the river with a magic rake, gathering up the pieces and, with some supernatural assistance, sews them back together.

The legends are usually billed as a “suite”—carrying with it associations of dance and theater—but they could easily pass as a four-movement symphony: the Maidens legend is the expansive first movement, The Swan is the slow movement, and Lemminkäinen in Tuonela takes the role of a symphonic scherzo. But this isn’t joking or playful music, as you might expect from a scherzo—this legend is sinister and edgy.

The fourth movement of this epic “symphony” is Lemminkäinen’s Return, in which the resurrected Lemminkäinen is persuaded to return home. In this legend, Sibelius brings together musical ideas from the preceding movements in the manner of a symphonic finale.

When Sibelius was interviewed in 1919, he explained that the underlying sentiment in Lemminkäinen’s Return was national pride: “I think we Finns ought not to be ashamed to show more pride in ourselves,” he said. “Let us wear our caps at an angle!” Listen to the jaunty motif in the brass as the legend begins—this music conveys all the optimism and confidence of a young composer at the vanguard of Finnish music.

Sibelius conducted the first performance of the Four Legends in 1896. He was nervous, which bothered the musicians, but the suite was well-received and Karl Flodin, the most influential critic in Helsinki, gave special praise to the first legend. He liked its modern, cosmopolitan feel, and approved of the influence of Liszt and Wagner. The following year, Sibelius conducted an extensively revised version of the suite. The public was again enthusiastic, the critics and experts less so. As a result, only The Swan and Lemminkäinen’s Return were published, in 1901. Sibelius withdrew the other two legends, leaving them unperformed until further revised versions were heard in 1939, including at the New York World’s Fair. The Four Legends weren’t published as a set until 1954, and it’s noteworthy, but not entirely surprising, that this is the first time the SLSO has performed the complete suite.

Yvonne Frindle © 2025

| First performance | April 13, 1896, Sibelius conducting the orchestra of the Helsinki Philharmonic Society; Sibelius conducted a revised version of the suite on November 1, 1897, again in Helsinki, after which he withdrew Lemminkäinen and the Maidens on the Island and Lemminkäinen in Tuonela, leaving them unperformed until 1939. |

| First SLSO performance | The Swan of Tuonela: March 18, 1910, Max Zach conducting; Lemminkäinen’s Return: November 7–8, 2014, conducted by Hannu Lintu (also our most recent performances); this is the first time the SLSO has performed the Lemminkäinen Suite in its entirety |

| Most recent SLSO performance | The Swan of Tuonela: September 28, 2014, conducted by David Robertson, with Cally Banham playing English horn |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (both doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 50 minutes |

Artists

John Storgårds

John Storgårds has a dual career as a conductor and violin virtuoso and is widely recognized for his creative flair for programming as well as rousing yet refined performances. He is Chief Conductor of the BBC and Turku philharmonic orchestras and Principal Guest Conductor of the National Arts Centre Orchestra Ottawa, and as Artistic Director of the Lapland Chamber Orchestra for more than 25 years, he has earned critical acclaim for the ensemble’s adventurous performances and award-winning recordings. Previous titles include Chief Conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra (2008–15) and Artistic Partner of the Munich Chamber Orchestra (2016–19).

He has been a frequent guest with the SLSO since 2012. In addition he conducts the Berlin Philharmonic, all the major Nordic orchestras, and other leading orchestras throughout Europe; the BBC Symphony and London Philharmonic orchestras; and major orchestras in Australia and Japan. In the United States he has also conducted the Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and the Boston, Chicago, and Detroit symphony orchestras.

His vast repertoire includes the symphonies of Sibelius, Nielsen, Bruckner, Brahms, Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann. He also regularly performs premieres and many works are dedicated to him, including Nørgård’s Symphony No. 8 and Saariaho’s Nocturne for solo violin.

Highlights of the 2024/25 season have included two appearances at the BBC Proms with the BBC Philharmonic, as well as numerous return engagements, including the Bamberg Symphony, Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Cincinnati, Dallas, and Montreal symphony orchestras. In May he will chair the jury for the XIII International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition.

His award-winning discography includes cycles of symphonies by Sibelius and Nielsen, and three volumes of works by American George Antheil. He is recording the late symphonies of Shostakovich with the BBC Philharmonic, and in 2023, he and the BBC Philharmonic were nominated for Gramophone magazine’s Orchestra of the Year Award.

John Storgårds studied violin with Chaim Taub and was concertmaster of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Esa-Pekka Salonen, before studying conducting with Jorma Panula and Eri Klas. He received the Finnish State Prize for Music in 2002 and the Pro Finlandia Prize 2012.

Francesca Dego

Italian American violinist Francesca Dego is making her SLSO debut this week, following debut appearances this season with the London, Dallas, and Houston symphony orchestras, performing major concertos of the repertoire: Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Brahms respectively.

Other 2024/25 season highlights have included performances with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana, Sinfonica di Milano, La Toscanini, Orchestre de Cannes, and the Vancouver, Detroit, and San Diego symphony orchestras, as well as her debut with the Luxembourg Philharmonic, and a recital at Wigmore Hall.

In North America, she has also appeared with the National and Indianapolis symphony orchestras, and in 2023 jumped in at short notice to make

her Canadian debut with the National Arts Centre Orchestra, Ottawa. Internationally, she is in demand, appearing in Japan with the NHK, Tokyo Metropolitan, and Tokyo symphony orchestras; in Australia with the West Australian and Queensland symphony orchestras; and in Europe, where she performs with many of the leading orchestras. Highlights there include the Orchestre de Champs Elysées, Swedish Radio Symphony, and Bergen Philharmonic orchestras, Orchestra Haydn, Brucknerhaus Linz, St. Petersburg’s Stars of the White Nights Festival, and Bernstein’s Serenade at La Fenice.

In the UK, where she is based, she has appeared with the BBC Symphony, Hallé, Ulster, Philharmonia, Royal Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, City of Birmingham Symphony, and Royal Scottish National orchestras.

Her recent recording of the violin concertos of Busoni and Brahms (featuring Busoni’s cadenza) received the 2024 Franco Abbiati Prize. Other releases in her growing discography include the Mozart violin concertos (conducted by Roger Norrington), and in 2023 she made her LSO recording debut on the Apple Classical platform, performing a concerto by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

Following family tradition (her father was a well-known Italian journalist), she contributes to Suonare News, The Strad, BBC Music and Classical Music magazines, Musical Opinion, and Strings, and she recently published her first book, Tra le note (Among the Notes).

Francesca Dego plays a rare Francesco Ruggeri violin (Cremona, 1697).

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.