Dvořák’s Cello Concerto (April 26-27, 2025)

Program

April 26-27, 2025

Ruth Reinhardt, conductor

Andrei Ioniță, cello

Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969)

- Concerto for String Orchestra

- Allegro

- Andante

- Vivo

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963)

- Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter) Symphony

- Engelkonzert (Concert of Angels)

- Grablegung (Entombment)

- Versuchung des heiligen Antonius (Temptation of St. Anthony)

Intermission

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

- Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104

- Allegro

- Adagio, ma non troppo

- Finale (Allegro moderato)

Andrei Ioniță, cello

Radiant Warmth

This weekend we welcome to St. Louis Ruth Reinhardt—a young German conductor well known for her imaginative programming. In her concerts she focuses on composers of our own time, especially women of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, championing, among other neglected voices, Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz. Parallel to these (re)discoveries, she programs complementary or contrasting works by classic moderns such as Paul Hindemith, in combination with core works from the symphonic canon.

The result in this concert is a stimulating combination of styles and sound worlds. From Bacewicz, we hear clean neoclassical lines together with a rhythmic vitality reminiscent of Béla Bartók and perfectly judged writing for strings. Her music has an “eastern European soulful darkness,” says Reinhardt, but it’s also “full of fun and wit.”

Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler symphony draws on an opera he was writing in the 1930s, inspired by the relationship between artist and society. The symphony, which had been commissioned by conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler for the Berlin Philharmonic, was well received in 1934 but production of the opera was blocked by the Nazis. The ban was not, apparently, on artistic grounds. The German Ministry of Culture advised that “in the rejection of Hindemith…the value or lack of value of his creative work is beside the point. National Socialism puts the personality of the creative artist before his work.” Meanwhile, Joseph Goebbels denounced the composer as an “atonal noisemaker,” but on the evidence of the Mathis der Maler symphony nothing could be further from the truth.

With Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto we arrive at a work from the heart of the canon, and one of the greatest of all concertos. The cello is often described as the instrument closest to the human voice in its emotional power and, as Romanian soloist Andrei Ioniță points out, Dvořák takes full advantage of its singing quality in this “epitome of cello playing.”

Concerto for String Orchestra

Grażyna Bacewicz

Born 1909, Łódź, Poland

Died 1969, Warsaw

Grażyna Bacewicz (Graw-ZHEE-nah Bat-SAY-vitch) is proof that talent, training, a substantial body of work, and even recognition and awards during one’s life, do not guarantee a consistent place among frequently performed composers. Born in Poland, she was educated at the Warsaw Conservatory as a violinist, and then went to Paris, where in the mid-1930s she studied composition with the famed pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. She spent the second half of her career in the Soviet sphere, which in theory promoted total gender equality, and she gained international exposure through performances and prizes in the United States and Western Europe. And yet she mostly disappeared from international concert programs until recently. Perhaps Bacewicz herself wouldn’t have rued this situation, writing in 1960: “I’d rather die than to evoke pity in people… even if they did not perform my music, I would sit in a corner and write, just like I am doing now.” But for listeners—especially those who otherwise appreciate, say, Ravel, Bartók, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich—her large catalogue offers much engaging music to be explored.

The Concerto for String Orchestra, written in 1948, is a strong place to start, with a first movement (Allegro) that shows off Bacewicz’s characteristic gruffness and idiomatic knowledge of string playing. The style might be described as neoclassical—that is, inspired by Baroque music, like a concerto grosso—but Bacewicz herself resisted the label.

The beautiful and unsettling slow movement (Andante) draws inventive colors from the string orchestra, with overlapping solos and shimmers of harmony. Bacewicz was steadfastly optimistic and practical in her outlook, but she had also lived through the total destruction of Warsaw in 1944 and had been a refugee for months after the German retreat. Approximately one-fifth of Poland’s population died during the Second World War, including both Polish Jews killed in the Holocaust and ethnic Poles who were also massacred by the Nazis or who died of malnutrition and disease. In August 1945, Bacewciz wrote to her brother:

You have no idea at all what we’ve gone through and how much we’ve had to endure… Suffice to say that Warsaw is no more, that the city is gone but for a few houses, that there is no railway station there, not a single bridge, nothing but heaps of ruins. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not exaggerating. You must have heard of the [August 1944] uprising in Warsaw, of how we fought Germans with little more than our bare hands, of how the Germans slaughtered the populace.

One can imagine that, just three years later, memories of this experience influenced her writing in the haunting middle movement. The finale (Vivo) regains the energy of the first movement, now in a wilder style, but also with an interceding lyrical idea based on massed chords, and shimmers carried over from the slow movement.

The concerto had to wait two years for a premiere at the 1950 General Assembly Polish Composer’s Union, after which it won a State Prize. A newspaper review reported: “It can be said in all honesty that the honor of Polish composers was saved this time by a woman, Grażyna Bacewicz.

Her Concerto for String Orchestra, written with panache and energy, full of smooth invention and brilliant instrumentation ideas, finally stirred us from our lethargy.”

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | June 18, 1950, at the General Assembly of the Polish Composers’ Union in City, Grzegorz Fitelberg conducting the Polish Radio Symphony |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | strings |

| Approximate duration | 15 minutes |

Mathis der Maler Symphony

Paul Hindemith

Born 1895, Hanau, near Frankfurt, Germany

Died 1963, Frankfurt

A composer under fire

Paul Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler (Matthias the Painter) was born of a collision between artistic ideals and political reality, which describes both the work’s subject and the conditions surrounding its creation. In 1932, Hindemith considered composing a work on the life of German Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald (c. 1475/80–1528). At first, he found insufficient drama in the subject and turned to other projects. But historic events soon changed his mind. In January 1933, Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, and official denunciation of “decadent” modern artists began to issue from his Ministry of Culture. Hindemith was a prime target.

In these changed circumstances, the subject of “Matthias the Painter” took on entirely new meaning. In June 1933, Hindemith began writing an opera libretto that told an allegorical drama of an artist, Matthias, caught in a political maelstrom, the Peasants’ War of 1524. “He is gripped by the subject,” a friend reported, “the atmosphere in which he is steeped, the overall parallels between those former times and our own, and above all by the theme of the artist’s lonely fate.”

Hindemith was still in the early stage of his work on Mathis der Maler when he received a request from Wilhelm Furtwängler, conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, for a new orchestral piece. The composer had already planned to compose instrumental preludes and interludes for the opera, providing musical representations of panels in the Isenheim Altarpiece, Grünewald’s most famous work. Not wishing to disrupt his concentration on the opera, he adapted three of these numbers to create a symphonic score.

The resulting Symphonie Mathis der Maler was loudly applauded and favorably reviewed, and its success persuaded Hindemith that a production of the opera would proceed routinely. This was not to be. In June 1934, the Nazis banned Hindemith’s music from radio broadcast. Permission to produce Mathis der Maler was denied soon thereafter. The opera was finally staged in 1938 in Switzerland, where Hindemith would soon be living as a refugee.

Music angelic and human

The first of the symphony’s three movements (Concert of Angels) is drawn from the prelude to the opera. It opens with “celestial” chords and a melody, announced by the trombone, based on a folk tune whose title translates “Three Angels Sang a Sweet Song.” Hindemith then proceeds to the main portion of the movement, whose climax is marked by a return of the folk tune.

The second movement (Entombment) represents a painting showing the internment of Christ and is drawn from an interlude in the final scene of the opera. The tone is subdued and reverent. The third movement is compiled from music in the sixth tableau of the opera. In this scene, Matthias relives the temptations of St. Anthony, as various characters from the opera—including a chorus of demons—appear in a vision and tempt him with pleasure and power. Matthias resists, and the symphony closes with a great hymn of thanksgiving.

Adapted from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2012

| First performance | March 12, 1934, Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic |

| First SLSO performance | January 22, 1943, Vladimir Golschmann conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | December 1, 2012, conducted by David Robertson, who also conducted the work on tour in Santa Barbara, California on March 20, 2013 |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (both doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 27 minutes |

Cello Concerto

Antonín Dvořák

Born 1841, Nelahozeves, Bohemia

Died 1904, Prague

The soloist’s entrance in Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto is as indelible as any in the repertoire. Tightly constructed yet expansive in feeling, the theme is self-assured—quickly crunching into five chords, then repeating itself higher, before continuing on into a virtuosic caprice. None of the ideas are new, having already been heard in orchestral guise through the three-and-a-half minute introduction. But the soloist adds an electric individuality that makes the same music sound entirely different when heard again.

Dvořák wrote the concerto between November 1894 and February 1895 in New York. It was his last, and least happy, academic year in the United States as director of the National Conservatory, a job for which he had been recruited in 1892 by the American philanthropist Jeannette Thurber. She hoped he would educate local musicians and spur a national style of classical music like he had in Bohemia. In the words of H.L. Mencken, he was hired to “introduce Americans to their own music.” And so he wrote his American String Quartet and New World Symphony, loosely integrating elements of African American and Native American musical traditions.

He enjoyed teaching in New York and spending a summer among Bohemian immigrants in Spillville, Iowa. But the Panic of 1893 (the worst economic crisis before the Great Depression) left the National Conservatory’s finances—and Dvořák’s expensive salary—in jeopardy. He returned to Bohemia for good in April 1895, penning a bitter goodbye in Harper’s Magazine lamenting the lack of government support for music in America and pointing out how his own career had been made possible by an Austrian State Stipendium.

The enduring popularity of Dvořák’s American works far outstrips their success in inspiring a homegrown repertoire in the same vein. His Cello Concerto, however, clearly led to the flourishing of the cello repertoire in the 20th century: without him, it’s unlikely that Elgar and Shostakovich, for instance, would have written their own. In fact, in the late 19th century, there were still doubts about the cello’s suitability as a solo instrument. Despite a number of virtuoso players and earlier concertos by Joseph Haydn, Robert Schumann, and Camille Saint-Saëns, the cello was generally regarded as a bass and tenor instrument with an unreliable upper register.

Dvořák was wonderfully surprised in 1894 when he heard Victor Herbert, a composer and principal cellist of the Metropolitan Opera, play his own Cello Concerto No. 2 with the New York Philharmonic. In Herbert’s hands, the cello could sing and zing as brightly as the violin, and the brilliance of this now-obscure piece convinced Dvořák to complete a cello concerto himself. (He had drafted but never orchestrated an earlier cello concerto, in A major, in 1865.) When the elderly Brahms heard Dvořák’s concerto, he was amazed in turn, saying, “If only I’d known, I’d have written one long ago,” while the Austrian critic Eduard Hanslick declared, “Dvořák has written a magnificent work which has brought to an end the stagnation of cello literature.”

Dvořák’s intended soloist was Hanuš Wihan, a Czech cellist whose technical advice he accepted, but whose request to add extra cadenzas he strongly rejected. Due to some scheduling confusion, the March 1896 premiere went instead to the English cellist Leo Stern and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, with Dvořák conducting. The score was published by Simrock in Berlin that same year.

The Music

The Cello Concerto was Dvořák’s last major orchestral work, following on the tail of the New World Symphony. (He spent his last decade focusing on operas and tone poems, mostly based on folklore.) Like the New World, the concerto inhabits a melancholy minor-key world, but it doesn’t directly quote any American themes, and by the finale it has landed entirely back in Bohemian territory. The first movement (Allegro) contrasts the bold solo theme (first heard hesitantly in the clarinets) with a beautiful melody first heard in the horn. The cello and orchestra share all the same material, as if the soloist is continuously absorbing and adapting elements found in its environment.

The middle of the slow movement (Adagio, ma non troppo) quotes one of Dvořák’s own songs from 1888, called “Kéž duch můj sám” (Leave Me Alone), Op. 82 No. 1. This was a favorite of his sister-in-law, Josefina Kaunitzová, with whom he had once been in love before settling for her younger sister, Anna. While working on the concerto in New York, he received word that Josefina was very ill in Bohemia, and was moved to pay tribute to her in the piece.

The finale (Allegro moderato) is quintessentially Czech in its wound-up, folksy energy—probably reflecting Dvořák’s excitement at returning home. But just a month after arriving back in Prague, Josefina died from her illness, and he decided to revise the third movement to encompass more elegiac references to her in an extended coda. The “Leave Me Alone” theme returns, and the soloist grows contemplative. It was Dvořák’s very personal conception of the movement that made him adamant in rejecting any suggested cadenzas. He explained to his publisher: “It has to remain the way I have felt it and thought it out… The finale ends gradually in a diminuendo, like a slow exhalation—with reminiscences from the first and second movements—the solo fades away to pp [very soft], then there is a crescendo, and the last measures are taken up by the orchestra, ending stormily. That is my idea and I cannot abandon it.”

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | March 19, 1896 at Queen’s Hall, London, the composer conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra with Leo Stern as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | February 12, 1916, Max Zach conducting with Pablo Casals as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 16, 2016, Hannu Lintu conducting with Alban Gerhardt as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo cello; 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 3 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, strings |

| Approximate duration | 41 minutes |

Artists

Ruth Reinhardt

Ruth Reinhardt is music director designate of the Rhode Island Philharmonic, commencing in 2025/26 as the fifth music director in the orchestra’s 80-year history. She is especially known as a champion of late 20th- and early 21st-century repertoire, frequently introducing audiences to new names and fresh faces in programs that build complementary parallels with classic moderns and works from the symphonic canon. This week she makes her SLSO debut.

This season she conducts orchestras in Europe, and North and South America, and makes her Asian debut, conducting the Seoul and Hong Kong philharmonic orchestras. She began the season at the Lucerne Festival with a program celebrating Pierre Boulez, and made debut appearances with the Bamberg and Nuremberg orchestras, Beethovenhalle in Bonn, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, and Residentie Orchester in the Hague. In addition to the SLSO, her US appearances include her Charlotte Symphony Orchestra debut and concerts in Milwaukee and San Diego. Highlights from recent seasons have included appearances with the New York Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, and in Detroit, Houston, Baltimore, Milwaukee, and Seattle. In Europe, she has conducted the Orchestre National de France, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Tonkunstler Orchestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, and Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra (RSB).

Born in Saarbrucken, Germany, Ruth Reinhardt studied violin and composition, and wrote an opera while still in high school. At the Zurich University of the Arts, she studied violin with Rudolf Koelman and conducting with Constantin Trinks and Johannes Schlaefli; at the Juilliard School of Music she continued in the conducting class of Alan Gilbert and James Ross. After graduating, she joined the Dallas Symphony Orchestra as assistant conductor to Jaap van Zweden, and was simultaneously a Los Angeles Philharmonic Dudamel Fellow, and assistant conductor to Lucerne Festival Academy artistic co-directors Wolfgang Rihm and Matthias Pintscher. Previous fellowships include the Seattle Symphony (2015–16), Tanglewood Music Center (2015), and Taki Concordia associate conducting fellow (2015–17). She currently resides in Switzerland.

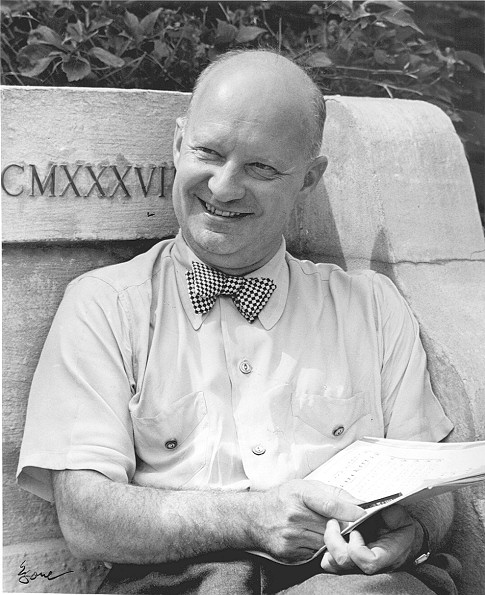

Andrei Ioniță

Romanian cellist Andrei Ioniță is making his SLSO debut this week. A versatile musician focused on giving gripping, deeply felt performances, he came to wide attention when he won the Gold Medal at the 2015 XV International Tchaikovsky Competition. He was subsequently named a BBC New Generation Artist (2016–18), and in 2017 made his US debut, with recitals in Chicago, Washington, DC, and Carnegie Hall’s Zankel Hall.

His engagements in the 2024/25 season include performances with the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Geoffrey Robson, and a trio performance with William Hagen and Anton Nel for Chamber Music in Oklahoma.

Recent highlights have included performances with the Chicago, Detroit, and San Diego symphony orchestras, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, Gewandhaus Orchestras, Munich Philharmonic, Danish National Symphony Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, and the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony, working with conductors such as Herbert Blomstedt, Kent Nagano, John Storgårds, and fellow Romanian Cristian Măcelaru. In 2019/20 he was the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra artist-in-residence.

He has given recitals at Konzerthaus Berlin, Elbphilharmonie, Zurich Tonhalle, LAC Lugano, and L’Auditori in Barcelona, as well as the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Schleswig-Holstein, Verbier, and Martha Argerich festivals. As a chamber musician he has collaborated with Martha Argerich, Christian Tetzlaff, Sergei Babayan, and Steven Isserlis.

Born in Bucharest in 1994, he studied first with Ani-Marie Paladi and later with Jens Peter Maintz at the University of the Arts in Berlin. Before winning the Tchaikovsky Competition, he won the 2013 Khachaturian International Competition, as well as Second and Special prizes at the International ARD Music Competition, and Second Prize at the 2014 Grand Prix Emanuel Feuermann in Berlin. In 2014 he released an acclaimed debut album, pairing the premiere recording of Brett Dean’s Eleven Oblique Strategies with solo cello works by J.S. Bach, Zoltán Kodály, and Svante Henryson.

Andrei Ioniță plays a cello made by Filippo Fasser from Brescia.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.