Dvořák’s New World (January 10-11, 2025)

Program

January 10-11, 2025

Daniela Candillari, conductor

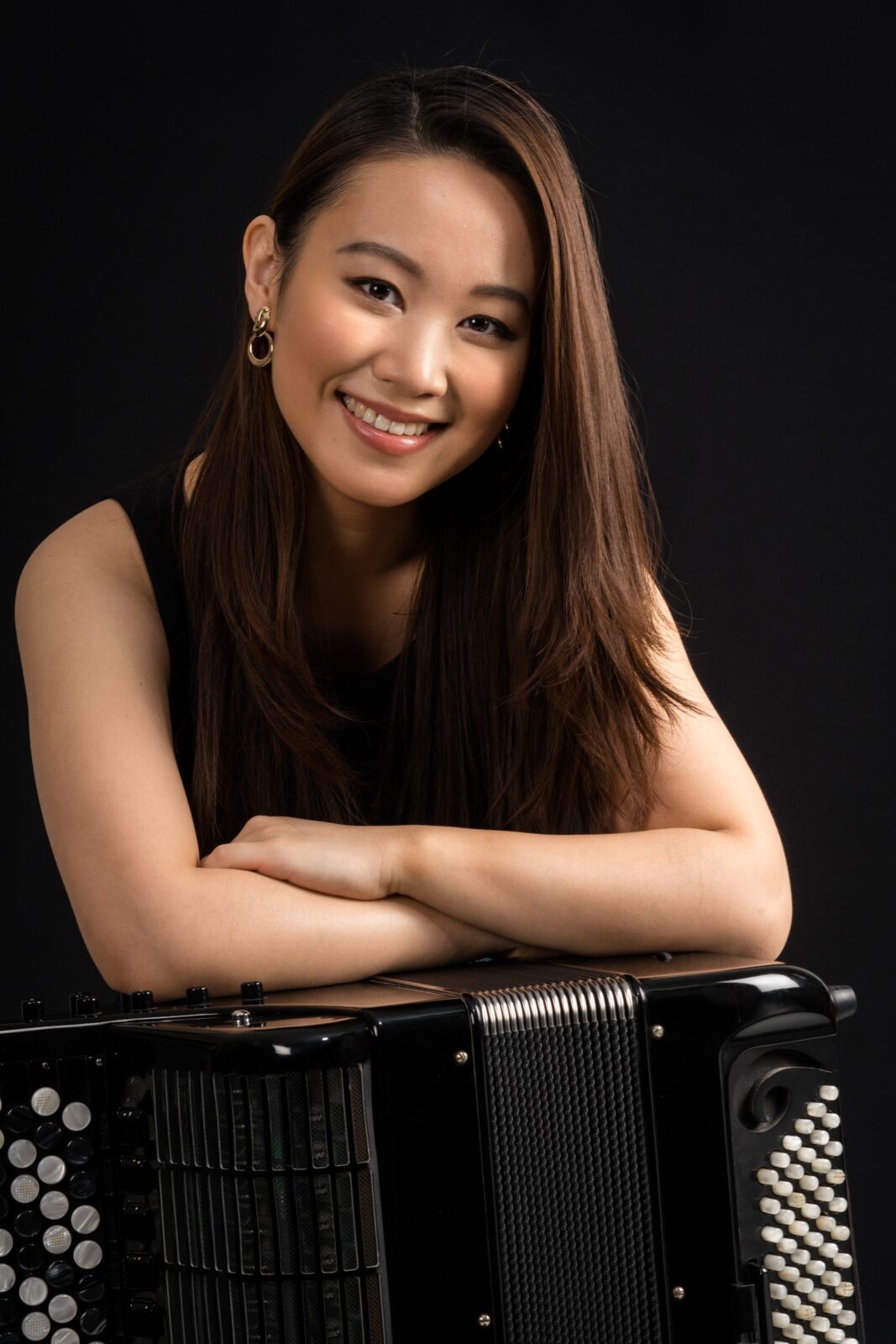

Hanzhi Wang, accordion

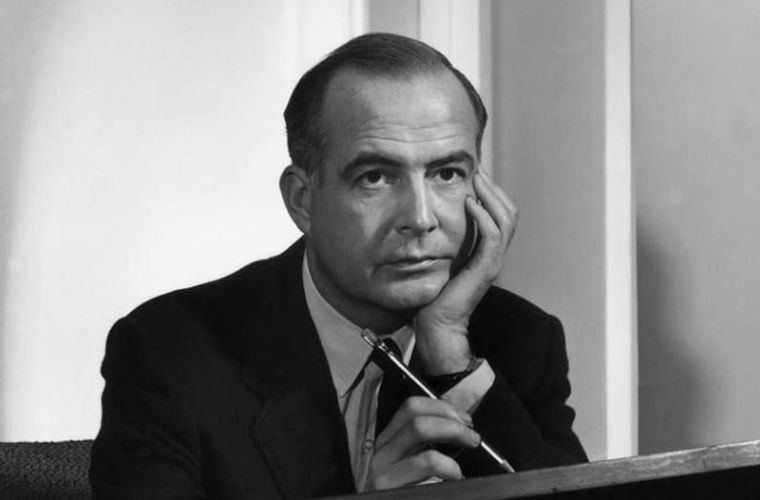

Samuel Barber (1910–1981)

- The School for Scandal Overture for Orchestra, Op. 5

Nina Shekhar (b. 1995)

- Accordion Concerto

Hanzhi Wang, accordion

World premiere

Commissioned by Young Concert Artists and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

Intermission

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904)

- Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, From the New World

- Adagio – Allegro molto

- Largo

- Scherzo (Molto vivace)

- Allegro con fuocoi

American Sounds

In 1892, Antonín Dvořák left his native Bohemia for New York, where he received a celebrity’s welcome. One of the world’s leading composers, he was the musician of choice when Mrs. Jeannette Thurber sought a director for her National Conservatory of Music, entrusting him with a bold vision: to nurture a distinctive national music—to find an American sound.

There’s irony in a European composer—in a European-style conservatory—being given the task of establishing a cultural identity independent of imported European ideas. But Dvořák’s experience as a Bohemian composer in Europe led him to believe that, for his students, the future lay in the sounds of Native American and African American cultures.

The music Dvořák himself composed in America was as much influenced by a nostalgia for home as by his immediate surroundings. The “From the New World” subtitle of his Ninth Symphony (added to the score in Czech) sets it up as a magnificent “postcard home.” This is the key to the famous Largo movement—a Dvořák original, which only later was turned into the “spiritual” “Goin’ home.” And it explains the appearance of a Czech dance in the middle of a lively third movement ostensibly inspired by Longfellow’s Hiawatha.

Move forward to the 1930s and a young American, Samuel Barber, has traveled in the opposite direction—from Philadelphia to Milan—spending the summer under the Italian sun, playing tennis and composing. The atmosphere is laidback, the inspiration is a gossipy 18th-century English comedy, the sound is all-American. The School for Scandal concert overture was Barber’s “postcard home,” and we can imagine Dvořák approving its spontaneous spirit and luminous sound.

The new American concerto in this program is less postcard and more love letter. Nina Shekhar is a first-generation Indian American, and in writing for the accordion she has found inspiration in the instrument’s distinctive sound. That sound reminded her of the hand-pumped reed organs used in Indian classical music and in turn the meditative and virtuosic techniques of her musical heritage. The result is gorgeous and thrilling and absolutely personal—a distinctive American voice. For Mrs. Thurber, more than 130 years on: mission accomplished.

The School of Scandal

Samuel Barber

Born 1910, West Chester, Pennsylvania

Died 1981, New York City

In 1931, young American composer Samuel Barber was inspired to write his first large-scale orchestral work. He was still a student at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and such iconic pieces as his Adagio for Strings and Violin Concerto still lay several years in the future. At Curtis, he studied with Italian composer Rosario Scalero and struck up a romance with a fellow composition student, Gian Carlo Menotti, also of Italian birth. In the summers, the two students would travel to Italy, staying with Menotti’s family near Milan, and driving every second week to continue their lessons with Scalero, who vacationed in Lombardy. It was in the summer of 1931 that Barber drafted the School for Scandal overture. He wrote home to his parents in Pennsylvania: “My new piece for orchestra goes well, but it is an effort to work at it! The day seems to go fast without any music. Generally we work from one until five of the afternoon, playing tennis in the morning.”

The “School for Scandal” title was taken from an English comedy written by Richard Brinsley Sheridan in 1777, but the music was not intended as an overture to a production of Sheridan’s play, rather as a concert overture and “musical reflection of the play’s spirit.”

It was two years before Barber secured a premiere—Fritz Reiner declined to program it with the Curtis Orchestra, but eventually the conductor Alexander Smallens picked it up for the Philadelphia Orchestra’s outdoor summer season. Barber couldn’t attend the August premiere because he was again back in Italy. But the overture won him the Joseph H. Bearns Prize from Columbia University, which came with a $1,200 grant that helped support more travels. An early review noted “a certain melodic facility and a sure sense of design, neither purely freakish in effect in the modern manner, nor complacently old-fashioned.” And within a few decades, what had begun as a student work entered the repertoire as a staple of modern American orchestral music.

The overture begins with series of shimmering chords, blindingly bright with a ringing triangle. The first thematic material is a bit nervous with fragments of melody jumping around, soothed when the oboe introduces a contrasting pastoral theme. While there are elements of madcap humor throughout the piece, there’s also a lyricism and emotional urgency that comes across as just a bit more serious than its namesake comedy of manners. It’s this kind of sincerity, often with a slight acerbic edge, that would define Barber’s mature style and legacy.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2024

| First performance | August 30, 1933, Alexander Smallens conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | February 3, 1945, with Stanley Chapple conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 28, 2010, with Ward Stare conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 9 minutes |

Accordion Concerto

Nina Shekhar

Born 1995, Detroit, Michigan

For many, the accordion might evoke images of a busker playing outside a Parisian cafe or the lively tunes of a Russian balalaika ensemble. For Nina Shekhar, however, its sound is reminiscent of the harmonium: a hand-pumped reed organ used in Indian classical music. This connection between the accordion and harmonium inspired her concerto.

The piece begins with an extremely slow descending three-note motif: A–G–F. (The first instrument heard is a pitched wine glass.) Its opening form resembles an alap, a slow, meditative section in Hindustani classical music that introduces a raag, or scale-like pattern, on which a composition is based. Drawing from Indian traditions, the concerto’s motif takes its time to develop. In the words of Shekhar, the first half is particularly “patient.”

When the accordion enters, it brings what Shekhar describes as an “otherworldly” quality. The accordion builds on the three-note motif, but in a spectral sense (that is, in a manner that plays with the harmonic series, or those notes present in the sound above the three notes in the original motif). The accordion joins an ethereal soundscape, created by vibraphone, harp, and piano, in addition to the pitched wine glasses. Microtones and pitch bending create expressive, haunting wails.

In the second half, the concerto builds on the ideas of the first, but in a new context. The second half begins with an expressive cadenza for the soloist and showcases the accordion’s virtuosity. The tempo increases. The many timbral capabilities of the instrument are explored. Techniques such as bellow shakes, where the accordionist shakes the bellows to produce fast repeated notes, and rapid shifts in range, demonstrate the instrument’s versatility.

What results is a concerto that not only showcases the dynamism of the accordion but also challenges the traditional concerto form. In Shekhar’s words:

The concerto—there is such a loaded connotation to that word. There are so many expectations of the hierarchy between the soloist and the orchestra and what that looks like. And in some ways, the fact that it was an accordion, which is an unconventional soloist for a typical concerto, made it a little bit easier for me to feel the strength to break some of those traditions… With this piece, it still does feel like a soloist with an orchestra. But I think it can blur the line in different ways. Sometimes there is a “follow the leader” relationship between the accordion and orchestra, but other times the accordion is fitting in within the texture of the orchestra to create a dense blur of chords.

Skyler Dykes © 2024

About the Composer

Nina Shekhar (pronounced Shay-ker) is a composer and multimedia artist, known for exploring identity, vulnerability, love, and laughter in her bold and intensely personal works. She was the Young Concert Artists Composer-in-Residence (2021–23), from which emerged this co-commission with the SLSO. She was also the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra’s 2023–24 Sound Investment Artist and her orchestral piece Glitter Monster was premiered by the LACO in May. She currently serves as Composer-in-Residence of Philadelphia chamber choir The Crossing. Her music has also been performed by the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Minnesota Orchestra, and Eighth Blackbird, to name a few, and has been heard in venues such as the Kennedy Center, Hollywood Bowl, and Carnegie Hall. In addition to composing, she performs on flute, piano, and saxophone, and has appeared at the Detroit International Jazz Festival. She studied composition at the University of Michigan (where she also earned a degree in chemical engineering) and the University of Southern California, and is a PhD candidate at Princeton. Nina Shekhar is a first-generation Indian American and native of Detroit.

On Writing for the Accordion

The accordion is a fascinating instrument with a rich history. After its invention in the 1820s, it quickly gained popularity around the world and became a vital part of many folk traditions, including European polka and klezmer music, Egyptian baladi, Brazilian baião, Korean trot, and Kenyan mwomboko dance music. While other instruments were often reserved for the aristocracy, the accordion has always been associated with the common people due to its distinctive sound, volume, portability, and ability to act as both a melodic and accompanying instrument. Historically, the accordion has been used far less frequently in classical music spaces, and its concert repertoire is fairly limited compared to other instruments.

Writing this concerto was an exciting opportunity to learn more about this amazing instrument and allow its unique sound world and extensive technical capability to enrich my own musical vocabulary. I’m extremely grateful to soloist Hanzhi Wang for her guidance; her musical virtuosity has deeply inspired me, and she is a wonderful ambassador for the instrument in our field.

–Nina Shekhar

| First performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | solo accordion; 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion, harp, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 23 minutes |

New World Symphony

Antonín Dvořák

Born 1841, Nelahozeves, near Prague, Bohemia

Died 1904, Prague, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic)

In September 1892, Antonín Dvořák, his wife, and two of their six children set sail for New York, where they would spend most of the next three years. Unlike so many other Czech immigrants before and after, they never intended to stay. The 51-year-old composer was lured to the United States by the American philanthropist Jeannette Thurber, a Paris-trained musician. Mrs. Thurber had already persuaded Congress to establish the National Conservatory of Music, her brainchild and life’s calling. Now she wanted Dvořák to serve as its director. He’d been reluctant at first, but the proposed salary of $15,000—more than 20 times what he’d been earning at the Prague Conservatory—made for an offer he couldn’t refuse.

In May 1893, when Dvořák was putting the finishing touches on his Symphony No. 9 in E minor (From the New World), he proclaimed in the New York Herald that “the future music of this country” should be founded on African American melodies: “This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States.”

Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony was the first of several works he composed entirely in the United States. Although he urged his National Conservatory students to explore indigenous musical forms, he had at that point heard only a smattering of American folk songs, mostly spirituals that his African American copyist Harry T. Burleigh sang for him.

So exactly how American is the New World Symphony? Although some listeners swear they hear traces of “Turkey in the Straw,” “Three Blind Mice,” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” Dvořák’s own statements are contradictory. While writing the symphony, he declared “the influence of America can be felt by anyone who has ‘a nose’.” But five years after he left the United States, he told a conductor preparing the Ninth for performance to “leave out the nonsense about my having made use of American melodies. I have only composed in the spirit of such American national melodies.” Elsewhere, he described all the compositions he’d written in the United States as “genuine Bohemian music,” and further stipulated that the Ninth’s title was meant only to describe “impressions and greetings from the New World.” Which is to say from the New World, not of it.

Questions of nationality aside, the Ninth is Dvořák’s most famous symphony for universal reasons: catchy tunes, sticky beats. The orchestration is luscious but restrained. The four movements are unified by the cyclical nature of the themes, which recur between movements in countless colors and patterns.

The first movement begins with a moody Adagio before the faster main section (Allegro molto) breaks up the Wagnerian grandeur with fiddle-happy forays and a bucolic-exotic pentatonic turn for flute and oboe. (It’s no accident that five-note pentatonic or “gapped” scales are distinctive of many cultures worldwide, in Czech folk song as well as those closer to home.)

The Largo movement presents the famous English horn theme, which is echoed and adapted by other instrument groups; at the midpoint, a new motive burbles up in the winds for a brief birdsong interlude. For this second movement, Dvořák found inspiration in Longfellow’s hyper-Romantic (and hugely inaccurate) 1855 ode to indigenous North Americans, The Song of Hiawatha, particularly the stanzas about the forest funeral of Minnehaha.

Next comes the hectic Scherzo, a mood-shifting cavalcade of dance forms. This movement also drew on Longfellow’s epic poem; Dvořák specifically cited the “feast in the woods where the Indians dance.”

The finale, a synthesis of the preceding three movements, brings it all back home. As promised by its Allegro con fuoco tempo marking, it is fast and fiery. But beyond the razzle-dazzle pyrotechnics, the finale radiates an elemental life force. This vital energy transcends national identity, maybe even identity itself. It doesn’t live anywhere. It just lives.

Adapted from a note by René Spencer Saller © 2017

| First performance | December 16, 1893, in Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Anton Seidl |

| First SLSO performance | March 13, 1905, Alfred Ernst conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 10, 2022, Stephanie Childress conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 43 minutes |

Artists

Daniela Candillari

Daniela Candillari is Principal Conductor of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis and Principal Opera Conductor at Music Academy of the West, Santa Barbara. She made her SLSO debut in June 2021 in a concert marking the partnership between the orchestra and OTSL. In addition to this week’s concerto premiere, in May she will conduct OTSL’s world premiere production of This House, in celebration of the company’s 50th anniversary season.

Other engagements this season include Madama Butterfly for Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, Gabriel Kahane’s emergency shelter intake form with NOVUS in New York, concerts at the Juilliard School and Manhattan School of Music, a return to New Orleans Opera for Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Delilah, and debut concerts with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra, Kansas City Symphony, and Tucson Symphony Orchestra.

In addition to conducting for Opera Philadelphia, Washington National Opera (Kennedy Center), Arizona Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Minnesota Opera, Detroit Opera, and the Metropolitan Opera, recent North American performance highlights include concerts with the Orchestre Métropolitan Montreal and the New York Philharmonic (conducting Yo-Yo Ma in Elgar’s Cello Concerto), and she made her Carnegie Hall Presents debut leading the American Composers Orchestra in a program of premieres.

Also a composer, she has been commissioned by instrumentalists from the Cleveland Orchestra; the Boston, Detroit, and Pittsburgh symphony orchestras; the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and the New York City Ballet Orchestra.

Daniela Candillari grew up in Serbia and Slovenia. She studied in Austria, and holds a Doctorate in Musicology from the Universität für Musik in Vienna, and degrees in Piano Performance from the Universität für Musik in Graz. In the United States, she completed a Master of Music degree in Jazz Studies at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music. She is also the recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship and a TED Fellowship.

Hanzhi Wang

An ambassador for her instrument, Hanzhi Wang has been praised for her captivating stage presence and performances that display passion and finesse, and she is the only accordionist to have won a place on the Young Concert Artists roster in its 60-year history.

A groundbreaking artist, her other firsts include being named Musical America’s New Artist of the Month, appearing on WQXR’s Young Artists Showcase as the first solo accordionist on the program, and recording the first solo accordion album on the Naxos label, On the Path to H.C. Andersen.

A First Prize Winner in the 2017 Young Concert Artists Susan Wadsworth International Auditions, she made her New York debut at Carnegie Hall’s Zankel Hall. For her Washington, DC debut, she opened the 40th Anniversary Young Concert Artists Series at the Kennedy Center. She also received the Ruth Laredo Prize and Mortimer Levitt Career Development Award for Women Artists of YCA, and won the 40th Castelfidardo International Accordion Competition in Italy.

She has given recitals at UC Santa Barbara’s Lively Arts, Stanford Live, Bravo! Vail, Krannert Center, Candlelight Concert Society, and the Morgan Library & Museum in New York City. She has also appeared as soloist with the Oregon Music Festival, Victoria Symphony, Cantori, Chamber Orchestra of the Triangle, Sinfonia Gulf Coast, Iris Orchestra, Hawai‘i Symphony Orchestra, Erie Philharmonic, and Reno Chamber Orchestra.

She inspires the next generation of accordionists with lectures, performances, and master classes at the Manhattan School of Music, Royal Danish Academy of Music, Tianjin Music Conservatory, Ghent Music Conservatory (Belgium), and in Norway and Portugal. In addition to Nina Shekhar, Martin Lohse, James Black, and Sofia Gubaidulina have dedicated works to her.

Hanzhi Wang earned her Bachelor’s degree at the China Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. She completed her Master’s degree and Soloist Diploma in Copenhagen, studying with Geir Draugsvoll at the Royal Danish Academy of Music.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.