Lintu Conducts Schumann (March 14 & 16, 2025)

Program

March 14 & 16, 2025

Hannu Lintu, conductor

Lawrence Power, viola

Kaija Saariaho (1952-2023)

- Ciel d’Hiver (Winter Sky)

Magnus Lindberg (b. 1958)

- Viola Concerto

- 1st Movement

- 2nd Movement

- 2a. –

- 2b. Trio

- 2c. Quasi una cadenza –

- 2d. Interlude –

- 2e. Cadenza

- 3rd Movement

Lawrence Power, viola

US Premiere

Intermission

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

- Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 68

- Sostenuto assai – Allegro, ma non troppo

- Scherzo (Allegro vivace) – Trio I – Trio II

- Adagio espressivo

- Allegro molto vivace

Nordic Love Letter

Over his many visits to the SLSO, Hannu Lintu has shown that he can’t be pigeonholed—his repertoire is as diverse as that of any of the leading conductors who’ve emerged from Finland in recent decades. We’ve heard him conduct American classics such as Corigliano’s Symphony No. 1, Romantic favorites by Dvořák, Grieg, and Tchaikovsky, and 20th-century Russian masterpieces by Stravinsky and Shostakovich. But he is also a champion of music of our own time—especially from his native Finland—and from this comes the “Nordic Love Letter” of today’s program: a recent work by the late Kaija Saariaho and the US premiere of Magnus Lindberg’s new viola concerto.

Saariaho’s ten-minute tone poem is an icy miniature, living up to its name, which translates as “Winter Sky.” Its exquisite atmosphere sets the scene for the magnificent virtuoso writing of Lindberg’s concerto, performed by its dedicatee, Lawrence Power. A review in The Guardian last year summed it up: “The solo writing is fiercely challenging, its orchestral counterpart sometimes deliciously intense; it’s an instantly attractive, strikingly communicative work.”

Despite its expansive, impressionistic, and occasionally explosive, character, the Lindberg calls for a relatively small “Classical” orchestra, with pairs of woodwinds, horns, and trumpets. It’s on the same scale as the orchestras Robert Schumann would have known—he adds just three trombones and timpani for his Second Symphony.

A Schumann symphony might seem to be an unusual “signature” for a Nordic love letter, but Hannu Lintu’s Finnish training (“Sibelius is our symphonic god”) has given him a deep affinity for the symphonic tradition and its transformation over time, as well as the combined attention to detail and sheer energy needed to make a Schumann symphony “work.” In his hands, Schumann’s Second makes a fitting conclusion for a concert that blends subtlety, delicate colors, and uplifting orchestral sound.

Ciel d’Hiver (Winter Sky)

Kaija Saariaho

Born 1952, Helsinki, Finland

Died 2023, Paris, France

Ciel d’hiver began as the second movement of a work for large orchestra, Orion, which Kaija Saariaho completed in 2002 for the Cleveland Orchestra. That piece took its inspiration from the hunter of Greek mythology—son of Poseidon—who was placed in the night sky as a constellation by Zeus after his death, thus capturing both the (hyper) active human being and the static heavenly object.

Saariaho re-orchestrated the second movement, Winter Sky, for a slightly smaller ensemble in 2013 on commission from Musique Nouvelle en Liberté, and this version, with its new French title, was premiered in 2014 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris by the Orchestre Lamoureux.

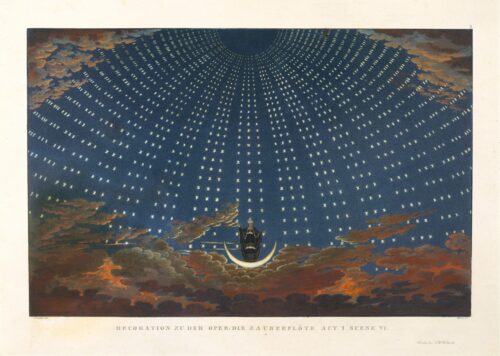

The opening is cold and glassy, laying down a bed of strings, harp, and percussion, on which a piccolo, a violin, and a clarinet rest. The timbre slowly shifts as other instruments take over, culminating in blocks of wind and brass. The middle section contrasts high and low masses of sound, moving between the stratosphere and the abyss. Eventually a piano pattern emerges, accompanying fragments of a solo cello melody. The piece captures the sweep and depth of the winter sky, its stinging cold and clarity, the slow drift and play of the constellations as they rise and set, and the immensity of it all.

About the composer

Kaija Saariaho belonged to a group of Finnish composers, also including Magnus Lindberg and Esa-Pekka Salonen, who founded the Korvat auki (Ears Open) society for contemporary music in the late 1970s. Beginning in 1982, she studied at IRCAM (in English the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music), the hotbed of electronic music research in Paris. Her work continued to be rooted in the avant-garde, with an ethereal beauty and sense of mystery—it feels not quite human, yet still makes a connection with us as listeners.

Saariaho’s accolades as a composer included the prestigious Grawemeyer Award and the Polar Music Prize, and two recordings of her works have won Grammy Awards. She spent most of her professional life in Paris, where she died of a brain tumor in June 2023, at age 70. Her final work, a trumpet concerto titled HUSH, received its posthumous premiere later that summer.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | April 7, 2014, in Paris with Fayçal Karoui conducting the Orchestre Lamoureux |

| First SLSO performance | Winter Sky, as a movement of Orion, was first performed on April 27, 2007, Robert Spano conducting; the revised work, Ciel d’hiver, was first performed October 7, 2022, Jonathon Heyward conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 10 minutes |

Viola Concerto

Magnus Lindberg

Born 1958, Helsinki, Finland

Belonging to the same generation of Finnish composers as Kaija Saariaho, Magnus Lindberg leaned toward super-complexity in his first decades as a composer, often writing intricate cross-rhythms with elaborately conceived tonal schemes. His early training was rooted in the European avant-garde, including studies with Einojuhani Rautavaara in Helsinki and Gérard Grisey in Paris. The founding of the Ears Open Society in 1980 with Saariaho, Salonen, and others, was an attempt to increase awareness of mainstream modernism. Since the late 1980s, his writing has turned toward comparative simplicity and lyricism, without abandoning its distinctive sense of orchestral color, harmony, and contrast.

Lindberg’s music has been performed worldwide by ensembles such as the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, London Sinfonietta, and Ensemble InterContemporain. He has won the Nordic Music Prize, Koussevitzky Prize, Royal Philharmonic Society Prize, and Wihuri Sibelius Prize.

Lindberg’s Viola Concerto is the most recent in a series of substantial works for solo instrument and orchestra, including three numbered piano concertos and a clarinet concerto, as well as several concertos for solo string instruments. “After having written two cello concertos and two violin concertos,” he wrote last year, “I thought for many years about composing a viola concerto. The instrument has played an important role in classical music… but it has enjoyed less prominence as a solo instrument. Yet the instrument is enormously rich, thanks to its different expressive modes, posing a huge variety of possibilities.”

The concerto unfolds in three movements, of which the second, at nearly 20 minutes, is the longest. Brass fanfares introduce the concerto and then mark the main sections, which follow the basic fast–slow–fast scheme of a traditional concerto. The long second movement is notable for its two cadenzas, separated by a brilliant interlude. In the second cadenza the soloist is invited to improvise if they wish, and in his recording of the work, you can hear Lawrence Power vocalizing to his own strummed accompaniment.

The sound world of the concerto reflects Lindberg’s newfound interest in clear, brilliant sonorities, employing pentatonic (five-note) harmonies, which are said to lend an “anti-gravity” feeling, unrooted from the bassline. The solo writing ranges from sultry to vigorously virtuosic.

Describing the form and style of the concerto, Lindberg writes:

I have often spoken about my way of working with musical material as an “extended Sonata form.” Rather than working with the contrasting difference between a main theme and a secondary theme, I typically have a collection of characters, with various degrees of contrast between them. [In the Viola Concerto] these characters follow each other in a whirlpool-like rapid manner, often giving the music a kaleidoscopic nature. This then undergoes a process of clarification towards more uniform expressions, employing a multitude of different techniques: filtering, diluting, variations, metamorphoses, developments, etc.

The concerto is dedicated to Lawrence Power who, in addition to giving the premiere in Finland and recording it for the Ondine label, has toured the work internationally, performing it with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Esa-Pekka Salonen in London, NDR Elbphilharmonie and Alan Gilbert in Hamburg, and Mozarteum Orchestra and Aivis Greters in Salzburg. “He is a musician I truly admire,” Lindberg writes in offering the dedication.

Adapted from a note by Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | February 28, 2024, in Helsinki, with Nicholas Collon conducting the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra and dedicatee Lawrence Power as soloist |

| First SLSO performance and US premiere | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, strings |

| Approximate duration | 34 minutes |

Symphony No. 2

Robert Schumann

Born 1810, Zwickau, Germany

Died 1856, Endenich (Bonn), Germany

Robert Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 took shape quickly and, it seems, easily. Toward the end of September 1845, Schumann wrote to his friend Felix Mendelssohn: “For several days drums and trumpets in the key of C have been sounding in my mind. I have no idea what will come of it.” Schumann did not wait long to find out. On December 12 that same year, the diary he kept with his wife Clara tells that he began composing a symphony, one in C major, with drums and trumpets playing conspicuous roles.

Once embarked on a composition, Schumann often worked with great speed. In this case, it took only five days to draft the new symphony’s initial movement and less than two weeks for the remainder of the work. But having made this rapid start, the composer fretted over orchestrating his piano draft, this task ultimately costing him much of the ensuing year. He eventually completed the work in October 1846, less than a month before its scheduled premiere.

Shortly after the first performance, several reviews extolled the symphony, and not just for its purely musical merits. More than one critic heard a lofty spiritual quality in the music, an aspiring toward almost religious expression. This is not entirely fanciful. Three of the symphony’s four movements use chorale-like melodies, and its signature theme seems nothing so much as a call from on high. There are no references to actual hymns, such as you’d hear in Mendelssohn’s “Reformation” Symphony, but in its own abstract terms, this symphony seems a kind of psalm, a song of praise and rejoicing.

Schumann begins the first movement with an introduction in moderate tempo (Sostenuto assai). Its initial measures present two ideas set against each other in counterpoint: a flowing line for the strings and a solemn fanfare in the brass. The latter figure will prove to be a “motto” theme, one that recurs at important junctures throughout the symphony. (If you’re familiar with Haydn’s last symphony, the “London,” you might note a resemblance between its opening fanfare and the one Schumann uses here.) Soon the music grows more active, its rhythms more animated, and the motto figure sounds again before the tempo accelerates into the Allegro, ma non troppo that forms the main body of the movement. Here Schumann fashions his themes using the buoyant rhythms introduced in the latter part of the introduction, and he revisits the motto again during the accelerated coda that brings this first portion of the symphony to a close.

The second movement seems to be an attempt to write a scherzo after Mendelssohn’s style, with light, running passagework in the violins. Yet the resulting style is still distinctly Schumann’s, thanks chiefly to the restless harmonies traced by the violin lines. Balancing this fleet music are two contrasting Trio sections, the second very like a hymn. The final statement of the scherzo includes another recollection of the motto idea.

Schumann builds the ensuing Adagio espressivo on a wide-stepping melody that seems more operatic than symphonic in character. It gives rise to the most beautiful slow movement among his orchestral compositions, a poetic romance intimating deep and tender reverie.

From the rocketing scale of its initial measure, the finale (Allegro molto vivace) strikes a triumphal note, and Schumann maintains this for practically the full length of the movement. There is a late recollection of themes heard earlier in the composition. Schumann weaves reminiscences of the aria-like melody of the slow movement into his development of the main subject, as well as reference to the motto theme. A more explicit recollection of the motto comes during the movement’s closing minutes.

Paul Schiavo © 2006

| First performance | November 5, 1846, with Felix Mendelssohn conducting the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | November 25, 1910, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | January 14, 2006, David Zinman conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 39 minutes |

Artists

Hannu Lintu

Hannu Lintu is a St. Louis favorite, this week making his 11th appearance with the SLSO. In 2024/25 he continues his tenures as Music Director of the Gulbenkian Orchestra and Chief Conductor of the Finnish National Opera and Ballet, proving himself a master of both symphonic and operatic repertoire. Later this year, he will also take up the post of Artistic Partner of the Lahti Symphony Orchestra. Guest conducting highlights of the 2024/25 season include his debut at the Bregenz Festival conducting Œdipe by George Enescu and return engagements with the Chicago, BBC, and Finnish Radio symphony orchestras, London Philharmonic Orchestra, and Oregon Symphony, as well as the SLSO.

In recent years he has conducted the New York Philharmonic (which led to an immediate re-invitation to conduct the orchestra at the Bravo! Vail festival), Berlin Philharmonic, Cleveland Orchestra, Bavarian and Swedish radio symphony orchestras, French National Radio Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Konzerthaus Berlin, Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, and Montreal Symphony Orchestra, collaborating with soloists such as Gil Shaham, Kirill Gerstein, Daniil Trifonov, and Sergei Babayan.

Opera highlights of recent seasons have included The Flying Dutchman

at Paris Opera and Pelléas et Mélisande at Bavarian State Opera, as well

as multiple productions for Finnish National Opera and Ballet, including a recent multi-season Ring cycle, Dialogues des Carmélites, Don Giovanni, a choreographed production of Verdi’s Requiem, Turandot, Salome, and Billy Budd.

His diverse discography includes recordings of Magnus Lindberg’s orchestral works, the Beethoven piano concertos with Stephen Hough, and the four Lutosławski symphonies, all with Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. He has also conducted several albums of music by Kaija Saariaho for the Ondine label.

Hannu Lintu studied cello and piano at the Sibelius Academy, where he also later studied conducting with Jorma Panula. He participated in masterclasses with Myung-Whun Chung at L’Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena, Italy, and in 1994 won the Nordic Conducting Competition in Bergen.

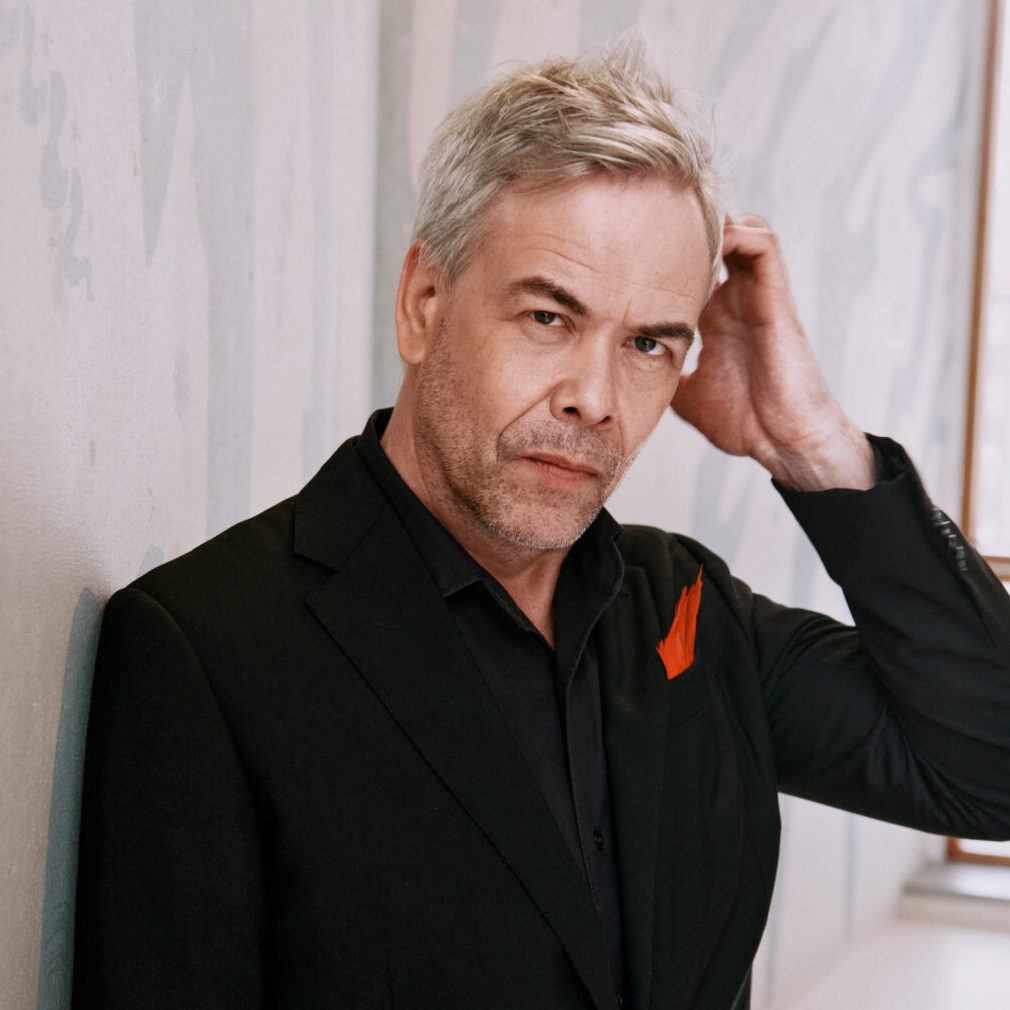

Lawrence Power

Internationally acclaimed violist Lawrence Power has advanced the cause of his instrument both through his performances and through the creation of the Viola Commissioning Circle (VCC), which has led to a substantial body of new repertoire by some of today’s finest composers. He has premiered concertos by composers such as James MacMillan, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Julian Anderson, and Alexander Goer, and through the VCC has commissioned works by Anders Hillborg, Thomas Adès, Gerald Barry, and Cassandra Miller, as well as Magnus Lindberg.

This season he is Resident Artist at the Southbank Centre in London, opening his residency in a recital with composer Thomas Adès at the piano and dancer-choreographer Jonathan Goddard. This was followed by the UK premiere of Lindberg’s Viola Concerto. In addition to giving local premieres of the Lindberg concerto in Germany, Austria, and the US (also his SLSO debut), season highlights include concerts with the Konzerthausorchester Berlin and Belgian National Orchestra, and a return to the Scottish Chamber Orchestra for the local premiere of Hillborg’s Viola Concerto.

He is a regular guest soloist with the Chicago, Boston, BBC, BBC Scottish, and Bavarian Radio symphony orchestras, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, and the Royal Stockholm, Royal Liverpool, Bergen, and Warsaw philharmonic orchestras. He works with conductors such as Osmo Vänska, Lahav Shani, Parvo Järvi, Vladimir Jurowski, Andrew Manze, Edward Gardner, Nicholas Collon, Ilan Volkov, and Esa-Pekka Salonen.

As a chamber musician, he is in much demand and regularly performs at Verbier, Salzburg, Aspen, Oslo, and other festivals with artists such as Steven Isserlis, Nicholas Alstaedt, Simon Crawford-Phillips, Vilde Frang, Maxim Vengerov, and Joshua Bell. In 2021 he was announced as an Associate Artist at Wigmore Hall, London, a five-year role.

Lawrence Power enjoys play-directing orchestras from both violin and viola, most recently the Scottish Ensemble (Edinburgh International Festival), Australian National Academy of Music, and Norwegian Chamber Orchestra. He also leads his own orchestra, Collegium, made up of fine young musicians from across Europe. He is on the faculty at Zurich’s Hochschule der Kunst and gives masterclasses around the world, including at the Verbier Festival.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.