Mendelssohn’s Reformation (October 18–19, 2024)

Program

October 18–19, 2024

David Danzmayr, conductor

Conrad Tao, piano

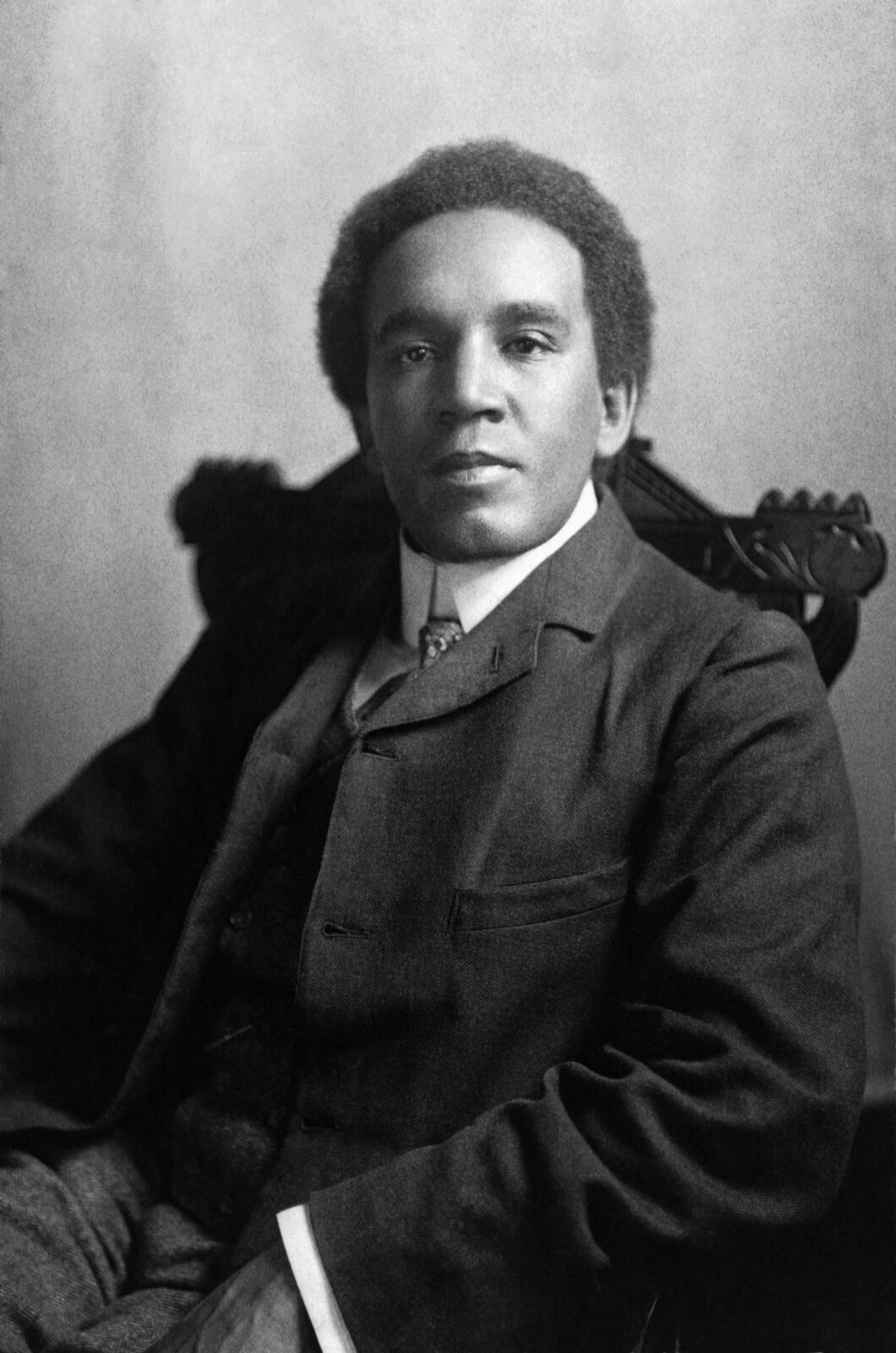

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912)

- Ballade in A minor, Op. 33

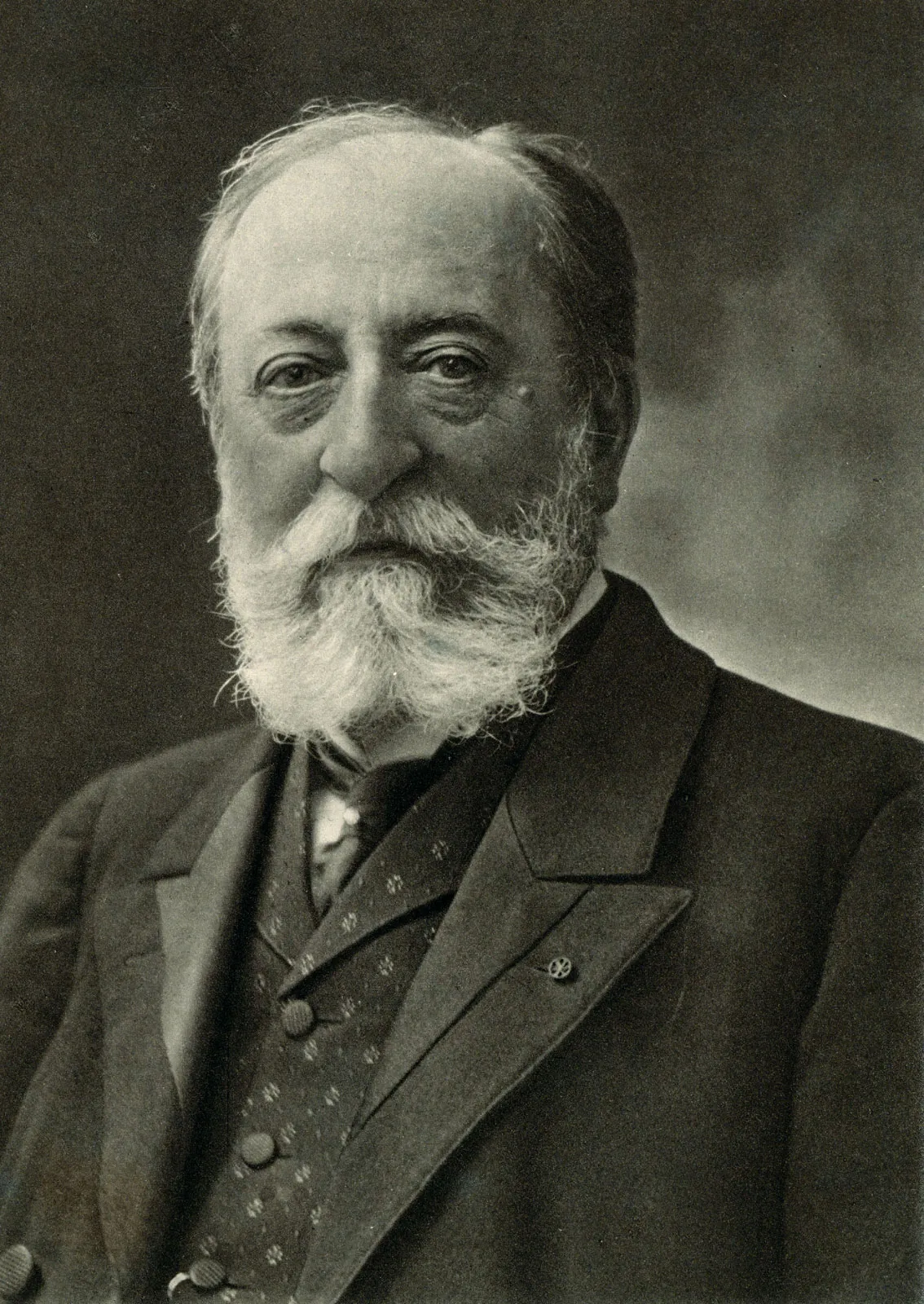

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835–1921)

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 22

- Andante sostenuto

- Allegro scherzando

- Presto

Conrad Tao, piano

Intermission

James MacMillan (b. 1959)

- One for chamber orchestra

The performance will continue without pause

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

- Symphony No. 5 in D major, Op. 107, “Reformation”

- Andante – Allegro con fuoco

Allegro vivace –

Andante –

Andante con moto – Allegro vivace –

Allegro maestoso

- Andante – Allegro con fuoco

Onward to Triumph

This concert begins with a literal triumph: the Ballade in A minor is the work that made Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s name when he was just 23 years old, assuring him celebrity status on both sides of the Atlantic for the remainder of his short life. And it’s all the more impressive given that Coleridge-Taylor had less than three months in which to write it.

Camille Saint-Saëns would say “hold my beer”: his Second Piano Concerto was completed in just 17 days! It was badly under-rehearsed at its premiere, but the music itself leaves nothing to apologize for and it has become the most popular of his piano concertos. Part of the appeal lies in the way it “begins with Bach and ends with Offenbach.” At the beginning it’s easy to imagine Saint-Saëns improvising in the organ loft; by the thrilling tarantella of the third movement, we’re in the sound world of the composer of the Can-Can. But the real triumph, at the premiere and ever since, is the witty central movement—glittering and good-humored.

Your ears will tell you otherwise, but according to the notoriously self-critical Felix Mendelssohn, his Reformation Symphony was anything but a triumph. He’d set out with high hopes, composing it on spec for a major Protestant anniversary celebration, but it was rejected by the programmers and failed to take off in other cities. By the time it was heard, the original inspiration and “Reformation” concept seemed less relevant and Mendelssohn tried to suppress it. But it’s impossible to hear this symphony as pure, “abstract” music, especially when Martin Luther’s famous hymn “A mighty fortress is our God” makes its appearance in the finale, emerging in a spirit of genuine triumph.

For this performance, conductor David Danzmayr has chosen to precede Mendelssohn’s symphony with a short work by Scottish composer James MacMillan. Like Mendelssohn’s finale, One begins with a solo flute, and its haunting, folklike atmosphere segues perfectly into the contemplative, slightly “antique” opening of the Reformation Symphony.

Ballade in A minor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Born 1875, London, England

Died 1912, Croydon, England

The Three Choirs Festival was one of 19th-century England’s most prestigious events, attracting audiences in the tens of thousands. For the 1898 festival, the Stewards invited Edward Elgar to write a “short orchestral thing.” As was customary, they offered no fee—creatives being asked to work for “exposure” is nothing new.

Elgar turned them down, but both he and his publisher, A.J. Jaeger of Novello & Co., endorsed a young composer just out of the Royal College of Music. “I wish, wish, wish, you would ask Coleridge-Taylor to do it. He still wants recognition and is far away the cleverest fellow amongst the young men,” wrote Elgar. Jaeger, aware that the festival was only a few months away, recommended him as a composer who’d write “a fine work in a short time. He has a quite Schubertian facility of invention and his stuff is always original and fresh.…Here is a real melodist at last.”

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born in London to a Krio doctor, Daniel Taylor, and a white British mother, who raised him after his father returned to Sierra Leone. Samuel’s maternal grandfather gave him his first violin lessons, and his prodigious talent won him a scholarship at the Royal College. He revered Antonín Dvořák and sought to integrate aspects of traditional African music into his fundamentally classical style, just as Dvořák had done with Slavonic music.

During his short life, Coleridge-Taylor won the support of leading cultural figures such as Henry Wood (of Proms fame) and George Grove, and in the U.S. the Black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. He was to make two celebrity visits to the U.S., where he was received by President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House.

Today, Coleridge-Taylor is best known for his cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, but it was the orchestral Ballade in A minor that made his name, winning him standing ovations from musicians and audiences, and enthusiastic reviews. The “exposure” did pay off, although he made the mistake of selling all rights to a work to Novello for 20 copies of the score.

The “Ballade” title was assigned by Samuel’s wife Jessie, also a musician, and she was spot on. The instrumental ballade was invented by Frédéric Chopin in the 1830s and the genre is best characterised as a kind of large-scale “song without words”: music full of dramatic intent without necessarily spelling out a story line. The ballade genre freed composers from Classical conventions such as sonata form and allowed them to play with bold gestures and contrasts of mood, as can be heard in the Ballade in A minor.

When Coleridge-Taylor visited America, some compared him to Mahler. But the Ballade in A minor reveals a stronger kinship to Tchaikovsky, with hints of the Russian composer’s Francesca da Rimini tone poem, in both the tempestuous opening theme and the soaring melodies of the more lyrical moments. The structure is straightforward—alternating the contrasting principle ideas—but any sense of repetition is balanced by Coleridge-Taylor’s marvelous instinct for orchestral color as well as the melodic gifts that Jaeger had recognized. As The Musical Times reported: “The feeling for real effect manifested throughout the work is most remarkable, and it is no wonder that this excellent performance given by the band called forth an exceptionally hearty outburst of enthusiasm.”

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

| First performance | September 14, 1898, in Gloucester, England, the composer conducting |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 12 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 2

Camille Saint-Saëns

Born 1835, Paris, France

Died 1921, Algiers, Algeria

Camille Saint-Saëns was one of the most fascinating musicians of the 19th century. During the course of a long career (he began composing at age four and continued to do so for the next 82 years) he produced an impressive quantity of music in every genre as well as distinguishing himself as a pianist, organist, and conductor. A man of considerable intellect, Saint-Saëns also wrote plays and poetry, studied archeology, astronomy, and other sciences, and wrote treatises on philosophy and ancient music.

Saint-Saëns composed his Second Piano Concerto in the spring of 1868 for a concert in Paris that was to be conducted by the Russian pianist and composer Anton Rubinstein. Because the performance had been hastily arranged, Saint-Saëns had to work quickly, and he completed the concerto in a mere 17 days. He played the solo part at the premiere. “Not having had the time to practice it sufficiently,” he recalled, “I played very badly, and except for the scherzo … it did not go well.” But despite its unhappy debut, the work has become the most popular of Saint-Saëns’ five concertos featuring the piano.

In this composition, Saint-Saëns adopted an innovative approach to the concerto form. The piece begins not with the customary orchestral exposition but with a long prologue by the solo instrument that evokes the sound world of J.S. Bach. (Saint-Saëns admitted later that he had come up with the opening while improvising at the organ.) Here we find an instance of the enduring influence of Bach on musicians of different temperament and outlook down through the generations. This opening idea is very much in the style of Bach’s keyboard preludes, though touched by a Lisztian type of virtuosity. This music returns, following the dramatic main body of the movement, to conclude the initial portion of the concerto.

In place of the customary slow second movement, Saint-Saëns offers a breathless scherzo, with fleet figuration and gossamer textures. Here, the composer assigns the opening gesture to the timpani, an effective and original touch with a “vamp till ready” character. It was a huge success: praised for its zest and vivacity.

The third movement (Presto) is in the style of a tarantella—the whirlwind dance that in popular tradition would cure a spider bite—and with this tour de force of energy and bravura piano writing he brings the concerto to a brilliant and thrilling conclusion.

Adapted from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2024

| First performance | May 13, 1868, in Paris with Saint-Saëns at the piano and Anton Rubinstein conducting |

| First SLSO performance | January 7, 1909, Max Zach conducting, with Adela Verne as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 27, 2014, Leonard Slatkin conducting, with soloist Conrad Tao |

| Instrumentation | solo piano, 2 flutes 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 24 minutes |

One for chamber orchestra

James MacMillan

Born 1959, Kilwinning, Scotland

In the crowded field of composers who are writing extraordinary music in our time, James MacMillan is a stellar example. Not only is his style completely original—with its intriguing combination of classical, modern, and folk idioms—but his pointed yet sincere treatment of religious and political themes presents a deeply moving listening experience.

MacMillan’s One, however, is unique in that regard, existing as a piece of “absolute music”—there is no extramusical theme or accompanying narrative. Composed in 2012 for the 20th anniversary of the Britten Sinfonia, the Scottish composer described this brief work as a “monody for orchestra,” in which a single melody “blossoms into something other than its singularity.”

The melody is modal (that is, neither fully major nor minor) and it’s introduced by a solo flute, playing in the breathy style of a wooden folk instrument. MacMillan’s lifelong affection for folksong is demonstrated as the tune is delicately passed between instruments and colored by their distinct sonorities. Moments of silence add a sense of quiet awe and perhaps spontaneity, as if the tune is being dreamed up on the spot. The music soon becomes more active, but before it can be developed further, it evaporates into thin air.

Kevin McBrien © 2024

| First performance | October 27, 2012, in London, performed by the Britten Sinfonia |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 5 minutes |

Reformation Symphony

Felix Mendelssohn

Born 1809, Hamburg, Germany

Died 1847, Leipzig, Germany

“I can no longer tolerate the ‘Reformation’ Symphony, and of all my compositions it is the one I would most like to see burnt. It will never be published.” This is Felix Mendelssohn, writing to his friend Julius Rietz in 1838. It was an abrupt change of heart for a composer who’d spent months writing the symphony—his second—and then two years trying to organize a performance. It’s surprising, even for a composer who was notoriously self-critical. What happened?

There are two likely factors. The first is frustration at what hadn’t happened since the completion of the symphony in 1830. The symphony was not—as Mendelssohn had hoped—programmed for the Berlin celebrations of the 1830 tercentenary of the Augsburg Confession, a major Protestant festival. The organizers had instead opted for choral works in an antique style by Eduard Grell. And it had not been embraced by concert presenters in other cities—not in Leipzig; not in Munich, even though a private play-through on piano was well-received; not in Paris in 1832, where it was rehearsed but rejected as too academic.

Mendelssohn hadn’t even attempted a performance in London even though he was popular there. Perhaps the Paris rehearsal had revealed flaws he wanted to correct. Eventually the Reformation symphony was revised and premiered in Berlin in 1832 to mixed reviews. In particular, Ludwig Rellstab criticized it for being modelled too closely on Beethoven’s “late colossal works” and for its “wrong-headed” attempt to express an extra-musical idea (“the Celebration of the Reformation Festival”) in symphonic form.

The Reformation Symphony was heard once more in Mendelssohn’s lifetime: conducted by Rietz in Düsseldorf in 1837. Mendelssohn didn’t attend but it’s this performance that appears to have triggered his about-face, leading to the second factor.

Between 1830 and 1837, Mendelssohn’s views on music and its relationship to language shifted. He declined, for example, to give titles to his evocative Songs without Words for piano, and he began to question the practice of supplying “programs” or literary outlines for music, mocking the often fanciful commentaries these inspired.

Mendelssohn had composed the Reformation symphony with a concept in mind, even though he didn’t supply a detailed narrative, and in 1832 the symphony had been performed with its title. By 1837 he’d adopted the view that music should be able to convey meaning without a supporting program and he’d evidently asked that no title or explanation be given to the Düsseldorf audience. Rietz reported that the symphony was enthusiastically received but “people were racking their brains trying to figure out what it was supposed to mean.” Mendelssohn’s conclusion: the symphony was a juvenile failure. Our conclusion? This is a symphony where awareness of the composer’s intention really does help in understanding his musical choices.

The lengthy slow introduction, for example, evokes the weaving vocal lines of Renaissance church music, suggesting the sound world of 1530 and perhaps the Catholic Church—although 19th-century Lutherans also embraced this style as most appropriate for the church, hence the choice of Grell’s music. Towards the end of this introduction, the first violins enter for the first time, playing the six-note rising “Dresden Amen” theme with its liturgical associations.

The central movements are lighter—a lively scherzo and graceful slow movement—and more tenuous in their connection to the Reformation theme. Even so, Mendelssohn recognized the festive mood and colorful flags of a Corpus Christi procession in the lively second movement with its trilling woodwinds.

The finale introduces the second borrowed quotation: Martin Luther’s famous hymn, “Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott” (A mighty fortress is our God). The choice of solo flute for this quotation is no accident: it was Luther’s own instrument. The hymn, or chorale, is developed in a hybrid structure—sonata form and variation form—that Rellstab and others would have recognized as a nod to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. In expressive terms, it’s as if the symphony rallies around this external musical idea, achieving a state of triumph and celebration.

Yvonne Frindle © 2022/2024

| First performance | November 15, 1832, in Berlin, conducted by the composer |

| First SLSO performance | December 10, 1948, Charles Munch conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 12, 2022, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 27 minutes |

Artists

David Danzmayr

David Danzmayr is in his fourth season as Music Director of the Oregon Symphony. He is also Music Director of the versatile ProMusica Chamber Orchestra, and Honorary Conductor of the Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestra, having previously served as Chief Conductor (2016–2019).

He has won prizes in the International Gustav Mahler and International Malko conducting competitions, and was awarded the Bernhard Paumgartner Medal by the Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum. He has quickly become a sought-after guest conductor, and his U.S. engagements include the Cincinnati, Minnesota, Seattle, Baltimore, Atlanta, Indianapolis, Detroit, North Carolina, San Diego, Colorado, Utah, Milwaukee, Houston, and New Jersey symphony orchestras, as well as the Pacific Symphony, Chicago Civic Orchestra, Grant Park Music Festival, and the SLSO.

In Europe and the U.K., he has led the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Bamberger Symphoniker, Sinfonieorchester Basel, Mozarteum Orchester, Essener Philharmoniker, Hamburger Symphoniker, Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Odense Symphony, Salzburg Chamber Philharmonic, Bruckner Orchester Linz, and the Vienna and Stuttgart radio symphony orchestras. He frequently appears in the world’s major concert halls, such as the Musikverein and Konzerthaus in Vienna, Grosses Festspielhaus Salzburg, Usher Hall Edinburgh, and Symphony Hall in Chicago.

He received his musical training at the University Mozarteum in Salzburg where, after initially studying piano, he went on to study conducting in the class of Dennis Russell Davies; he subsequently joined Leif Segerstam’s conducting class at the Sibelius Academy, Helsinki. As a student, he received a conducting scholarship from the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, where he was strongly influenced by Pierre Boulez and Claudio Abbado. He also gained significant experience as an assistant to Neeme Järvi, Stéphane Denève, Andrew Davis, and Pierre Boulez, who entrusted him with the preparatory rehearsals for his own music.

Conrad Tao

Conrad Tao made his scheduled SLSO debut in 2014, playing this evening’s concerto in an “effortless” performance that the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “radiating pleasure.” But his actual debut had taken place the previous season, when he’d stepped in at short notice to perform Prokofiev’s demanding Piano Concerto No. 3; he was just 18.

Since then, he has established himself as both pianist and composer, appearing as a soloist in traditional repertoire with leading orchestras, as well as in innovative recital and collaborative projects. This season, his engagements include a Carnegie Hall recital (performing Debussy Études alongside Keyed In, an improvised work on the Lumatone) and a U.S. tour with dancer-choreographer Caleb Teicher, as well as return visits to the San Francisco, Baltimore, and Dallas symphony orchestras, and the season opening gala for the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra.

In the 2023/24 season he made his subscription debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, performed with the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Philadelphia Orchestra, and celebrated Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversary with recitals for the Cleveland Orchestra and the Ruhr Piano Festival. He also gave 100th anniversary performances of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue in Germany and Amsterdam, together with his companion piece, Flung Out.

His first large-scale orchestral work, Everything Must Go, was premiered by the New York Philharmonic, and he received a New York Dance and Performance Bessie Award for his work on More Forever, in collaboration with Caleb Teicher. He is also an Avery Fisher Career Grant recipient and a Gilmore Young Artist. He has released several albums featuring traditional repertoire, his own music, and experimental work, most recently Bricolage with The Westerlies brass quartet.

Conrad Tao was born in Urbana, Illinois. He studied piano with Emilio del Rosario in Chicago and Yoheved Kaplinsky in New York, and composition with Christopher Theofanidis.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.