Mozart’s Requiem (November 9–10, 2024)

Program

November 9–10, 2024

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Joélle Harvey, soprano

Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano

Josh Lovell, tenor

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone

St. Louis Symphony Chorus

Erin Freeman, chorus director

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

- Adagio and Fugue in C minor, K.546

Detlev Glanert (b. 1960)

- Four Preludes and Serious Songs

- Based on the Four Serious Songs, Op. 121

- by Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

- Prelude to No. 1 –

“Denn es gehet dem Menschen” –

Prelude to No. 2 –

“Ich wandte mich, und sahe an alle” –

Prelude to No. 3 –

“O Tod, wie bitter bist du” –

Prelude to No. 4 –

“Wenn ich mit Meschen-und mit

Engelszungen redete” –

Postlude

- Prelude to No. 1 –

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone

Intermission

Mozart

Completed byFranz Xaver Süssmayr

(1766–1803)

- Requiem Mass in D minor, K.626

- Introit: Requiem æternam

Kyrie

Sequenz: Dies iræ. Tuba mirum. Rex tremendæ.

Recordare. Confutatis. Lacrimosa

Offertorium: Domine Jesu. Hostias

Sanctus

Benedictus

Agnus Dei

Communio: Lux æterna. Cum sanctis tuis

- Introit: Requiem æternam

Joélle Harvey, soprano

Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano

Josh Lovell, tenor

Dashon Burton, bass-baritone

St. Louis Symphony Chorus

Erin Freeman, director

Mozart’s Requiem: Joy and Sorrow

With this first program in Stéphane Denève’s November “Mozart Celebration” we begin at the end, making Mozart’s final masterpiece, his Requiem, the cornerstone. On this foundation, Stéphane has built a thought-provoking program that meditates on themes of death and belief, and explores the way in which composers look to the past.

Perhaps the most poignant aspect of Mozart’s Requiem is that it was left unfinished at his death. (The first eight measures of the Lacrimosa are the last notes in Mozart’s hand.) The Requiem survived—and has flourished—because Mozart’s widow arranged for a student to complete it.

Johannes Brahms’s Four Serious Songs (Op. 121) was similarly his last set of songs, and in part a response to the death of his friend Clara Schumann. The songs themselves, written for low male voice and piano, are complete, but Brahms also made a sketch, suggesting that he had in mind an orchestral version of the music.

This sketch leaves a tantalizing “What if?” and fellow Hamburg composer Detlev Glanert took up the challenge a century later: orchestrating the songs with reverential care and framing them with music of his own—interlocking Preludes that look back to Brahms.

In the opening work, Mozart also turns his eyes to the past, finding inspiration in the mighty fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach and their complex weaving of musical voices. By adding a declamatory Adagio as a slow introduction to his fugue, Mozart evokes another Baroque tradition: “preluding” or improvising to introduce and link pieces. The practice survived into the 19th century (Clara Schumann was known to do this in her piano recitals) and informs Glanert’s approach to his own Preludes. The mood of this concert is dark and melancholy—with layers of grief, pessimism, and even terror—but there’s tenderness, too, and a sense of deeply felt drama that pervades all three works and speaks to the modern imagination.

Adagio and Fugue in C minor, K.546

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born 1756, Salzburg, Austria

Died 1791, Vienna, Austria

On April 10, 1782, Mozart wrote from Vienna to his father in Salzburg: “I go every Sunday at noon to Baron van Swieten’s, where nothing is played but Handel and Bach. I am collecting at the moment the fugues of Bach.” Gottfried van Swieten, the Imperial Court Librarian in Vienna, was a literate and musical aristocrat who served as Austria’s ambassador to Prussia through most of the 1770s. During that service he’d become acquainted with the music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, who had long been employed as harpsichordist and composer at the Prussian court, and other members of the Bach family, including Johann Sebastian.

J.S. Bach’s music made such an impression that van Swieten came to regard the polyphonic tradition of the Baroque period as the pinnacle of composition, and he took it upon himself to convert others to that opinion after he returned to Vienna. The Sunday afternoon gatherings at his home hosted a select group of invited musicians—Haydn was also a regular attendee—and featured readings of Bach’s fugues and the great fugal choruses from Handel’s oratorios, works that were generally unknown in Vienna at that time.

For Mozart, the discovery of Bach—and particularly his fugal style, with its complex, interweaving voices—proved a revelation. He at once began not only “collecting” Bach’s fugues and arranging them for string trio (for performance at van Swieten’s) but writing fugues of his own. Among these was a technically ambitious fugue in C minor for two pianos (K.426) composed in December 1783. And in June 1788, Mozart arranged this music for string orchestra, adding to it a prelude in suitably grave style.

The resulting Adagio and Fugue in C minor (K.546) is remarkable in its intensity of feeling and compression of form. The Adagio is a dark fantasia, marked by restless melodic figures and considerable harmonic tension. Although more rigorous in its development of a single theme through imitative counterpoint, the Fugue is hardly less expressive, conveying through all its intricacies an unmistakable sense of emotional crisis. Fugue has traditionally been considered the most “learned” or academic of musical forms. Mozart shows here that it can be much more than an intellectual exercise.

Adapted from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2004

| First performance | Sometime after June 1788 |

| First SLSO performance | January 15, 1972, conducted by Alexander Schneider |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 3, 2004, conducted by Itzhak Perlman |

| Instrumentation | strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

Four Preludes and Serious Songs

Detlev Glanert

Born 1960, Hamburg, Germany

Detlev Glanert and Johannes Brahms have two things in common. Both composers were born in Hamburg, and they share a creative fascination with the past. Like Mozart before him, Brahms was attracted to the music of J.S. Bach. The finale of his Fourth Symphony, for example, builds on a theme from a Bach cantata. And Glanert frequently turns to the music of Brahms, orchestrating his chamber works and making compositional responses to his symphonies.

The Hamburg connection is more than an accident of birthplace. Glanert describes his affinity with Brahms as part of “a specific North German tradition […] to do with a melancholy in his pieces, with a certain severity.” And those two qualities pervade Brahms’s final work, his Four Serious Songs, amplified by the circumstances of its composition and his choice of texts.

The Songs were literally composed in the shadow of death: Brahms was dying of cancer and mourning the deaths of several close friends. Meanwhile, his dearest friend and champion, Clara Schumann, suffered a stroke in March 1896 and would herself die within weeks of the completion of the Songs in May. Their first public performance took place at the wake following her funeral.

The “godless” texts (Brahms’s word) of the first three songs are drawn from Ecclesiastes (Old Testament) and Ecclesiasticus (Apocrypha), and are characterised by a pessimistic and resigned view of death unsurprising for a nonbeliever such as Brahms. The fourth song—which had its origins in a song for Brahms’s muse Elisabet von Herzogenberg—adopts the famous passage on love from I Corinthians. These texts are at once personal in their candor and public in the universality of their themes, and Brahms’s powerful and emotive settings are regarded by many as the zenith of his career.

Glanert’s decision to orchestrate the Four Serious Songs and then link them with original preludes was motivated in part by the unrealized potential they represent. The original accompaniments, he explains, are “nearly out of the reach of a pianist’s fingers and thus beyond the world of piano sound alone.” Perhaps more important, Glanert took up the challenge presented by a single sheet of sketches that suggests Brahms was planning to orchestrate the songs himself, or perhaps expand the ideas into a symphonic work.

Glanert’s orchestrations use instrumental color to clarify the structure and intensify the expression, and he achieves this with an orchestral line-up similar to that of Beethoven or Brahms (the harp is the interloper), using those forces in ways that Brahms would have recognized. He doubles the middle voices to produce darker sonorities, for example, and his use of the woodwinds, often moving together in harmony, is another Brahms “fingerprint.” Out of respect, explains Glanert, he has tried to set the songs as “distinctively and scrupulously” as Brahms himself would have done.

“Respect” is the key word here, and the song orchestrations are stylistically faithful. The four preludes and the postlude are entirely Glanert’s, but even here, nearly all the musical kernels come from Brahms. Glanert describes the effect as beginning in Brahms’s world, sliding slowly into our own, and then falling back again. He also invites us to hear the preludes as a theological commentary on the texts: “The best way to gain an understanding of what I tried to do in the Preludes is to have in mind the lyrics of the preceding and following song.”

The first prelude, for example, begins by taking the end of the first song and presenting it backwards, and establishes a somber mood with the deepest sonorities in the orchestra. In the third prelude, Glanert transforms Brahms’s motives into an “angry waltz”—a nod to the 18th-century Hamburg tradition of the Totentanz (dance of death), which Brahms knew well—and veers into the sound world of Mahler. That post-Brahms vision continues in the fourth prelude, which seems pensive and calmer, but also suggestive of Mahler’s “haunted” late Adagios. The postlude quotes themes from each of the songs in the manner of an end-of-life flashback. The result is a true musical synergy, as Glanert interweaves the reverential orchestration of Brahms’s songs with an illuminating creative commentary that expands the sound world of the original.

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

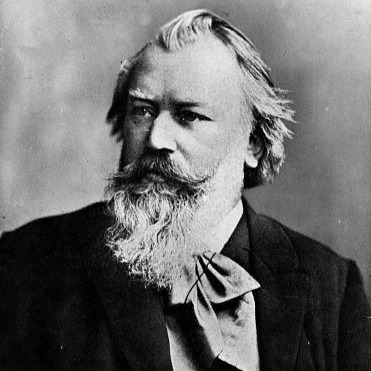

Johannes

Brahms

(1833–1897)

completed his

Four Serious Songs in 1896

after learning of the

death of Clara Schumann.

| First performance | June 25, 2005, in the Marienkirche in Prezlau, Germany, with soloist Dietrich Henschel and Kent Nagano conducting the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin |

| First SLSO performance | October 4, 2014, with soloist Patrick Carfizzi and Markus Stenz conducting |

| Instrumentation | solo baritone; 3 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 25 minutes |

Requiem

Mozart

You’ve probably encountered the legend surrounding Mozart’s Requiem. Although it makes for great theater, there’s no truth in the story of composer Antonio Salieri poisoning Mozart or attempting to frighten him by appearing as a masked figure in gray. But there was a mystery man: the “tall, thin, grave-looking” agent of Franz Count von Walsegg, who anonymously commissioned the Requiem—a setting of the Latin Mass for the Dead—with a view to passing it off as his own. This was not unusual for the Count, a dilettante musician who’d made a practice of commissioning works from professional composers and then taking credit for them. In this case the Requiem was to be performed in memory of his wife. According to an early biography, Mozart was told that attempting to identify his client “would assuredly be in vain.”

Despite the remarkable circumstances, Mozart was reportedly eager to try his hand at this “higher form of church music” and he almost certainly needed the generous fee. But a sudden, severe illness, probably rheumatic fever, may have led Mozart to believe he was writing his own requiem, and his death in December 1791 cut short his work, eight measures into the poignant Lacrimosa. In order to collect the fee, Mozart’s widow, Constanze, arranged for the Requiem to be completed by his student Franz Xaver Süssmayr, and while others have since made their own completions, it’s to Süssmayr that we owe the survival of this work in the repertoire.

A separate controversy has surrounded Süssmayr’s completion of the Requiem, which entailed composition of the Sanctus and Benedictus sections and parts of the Lacrimosa and Agnus Dei. Defense of his work includes the not fully documented hypothesis that a sheaf of papers Constanze allegedly gave Süssmayr must have contained sketches by Mozart. On the other hand, we have Beethoven’s blunt assertion that “If Mozart did not write this music, then the man who wrote it was a Mozart.” Others, however, have disputed Beethoven’s opinion, pointing to errors in counterpoint, as well as what they perceive as a lower level of inspiration in the sections fashioned by Süssmayr. More recent composers and scholars have attempted to complete Mozart’s score, but Süssmayr’s version is standard and seems likely to remain so, for despite what Süssmayr did or did not do for it, this Requiem is still one of the great settings of the Mass for the Dead.

Mozart’s Requiem is the work of a composer whose heart was in the opera house. Yes, it works perfectly well in a liturgical context, but the music’s dramatic and expressive range takes it beyond the scope of ritual function. The result is both intensely personal and, in sections such as the Dies iræ, furious and terrifying. These extremes are mirrored in the orchestral colors. Curiously, Mozart doesn’t include flutes, oboes, clarinets or horns, but there are parts for the mellow sound of the basset horn (a low-voiced member of the clarinet family, heard to remarkable effect at the very beginning, for example, and in the Recordare). Meanwhile, three trombones—instruments associated with church and theater at the time but unknown in concert music—contribute to fiercer moments such as the Confutatis. For the concluding section, Cum sanctis, Süssmayr reprised the music Mozart had written for the Kyrie—voices and instruments weaving together for a thrilling fugue in the style of Handel.

But for all the urgency and even drama in sections the Dies iræ, Mozart’s music lacks the apocalyptic tone we hear in the requiem settings by Berlioz and Verdi. This is more than a matter of his using a smaller orchestra. Rather, it reflects Mozart’s quite different attitude toward mortality. Some idea of this may be gleaned from an often-quoted letter the composer wrote to his father in 1787. In it, Mozart speaks of death as “the true goal of our existence … [the] best and truest friend of mankind, … [something] very soothing and consoling.” The music of his Requiem is precisely this, “soothing and consoling,” its profound beauty overcoming any sense of desolation and serving to put us on more intimate terms with our “best and truest friend.” Mozart, during his all too early maturity, must have felt no higher artistic purpose.

Adapted from notes by Yvonne Frindle © 2022 and Paul Schiavo © 2006

| First performance | Parts of the Requiem were performed in a memorial service for Mozart in Vienna on December 10, 1791; the full Requiem in Süssmayr’s completion was heard in a benefit concert for Mozart’s widow, Constanze, on January 2, 1793; Count Walsegg organized and conducted its first liturgical performance (under his own name) at the Neukloster monastery outside Vienna on December 14, 1793 |

| First SLSO performance | December 13, 1958, Edouard van Remoortel conducting, with soloists Irene Jordan, Jean Madeira, Lesley Chabay, and Mack Harrell; and the Washington University Choir, Men’s Glee Club, and Washington University Women’s Chorus |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 6, 2022, Patrick Summers conducting, with soloists Erica Petrocelli, Jennifer Johnson Cano, Nicholas Phan, and Soloman Howard; and the St. Louis Symphony Chorus |

| Instrumentation | Four vocal soloists and chorus; 2 bassett horns, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, organ, strings |

| Approximate duration | 55 minutes |

Artists

Joélle Harvey

Soprano Joélle Harvey returns to the SLSO after singing in Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in 2019. A native of Bolivar, New York, she began her career training at Glimmerglass Opera (now The Glimmerglass Festival) and the Merola Opera Program, after completing degrees in vocal performance from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (CCM). Since then, she has performed major roles on stages such as the Metropolitan Opera (Pamina in The Magic Flute), Glyndebourne Festival Opera (the title role in Semele), Royal Opera House, Zurich Opera, Teatro La Fenice, and the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

Her engagements this season began with Haydn’s Creation (Jane Glover and Music of the Baroque), and her 2024/25 debuts include a concert of Ravel and Boulanger with the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, her house debut at the Opéra Royal de Versailles singing Galatea in Acis, and Anna Truelove in The Rake’s Progress at Des Moines Metro Opera. Her concert appearances will include Messiah (Cincinnati and Houston symphony orchestras), and she returns to the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin for Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony, as well as Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society in an all-Handel program. She performs Bach’s St John’s Passion with the Orchestra of St Luke’s and a concert of Haydn with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Recent concert highlights include appearances with the Cleveland Orchestra (Franz Welser-Möst), the English Concert (with conductor Harry Bicket), Los Angeles Philharmonic (Gustavo Dudamel), Orchestra of St Luke’s (Bernard Labadie), Deutsches Symphony-Orchester Berlin (Robin Ticciati), and UK early music ensemble Arcangelo. She has also performed with the New York Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Jacksonville Symphony, New World Symphony, and National Symphony Orchestra.

Kelley O’Connor

Mezzo-soprano Kelley O’Connor returns to the SLSO having most recently sung Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde in the 2022/23 season. She performs a broad range of repertoire, from Beethoven, Mahler, and Brahms to Dessner, Corigliano, and Adams, and appears with leading orchestras and conductors around the world, in collaboration with preeminent artists for recitals and chamber music, and with opera companies such as Boston Lyric Opera, Los Angeles Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Cincinnati Opera, Opera Boston, Santa Fe Opera, and the Canadian Opera Company.

Later this year, she will perform in the premiere of the extended version of Thomas Adès’s America (A Prophecy), first in her debut with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchester under Andris Nelsons, and in 2025 with The Cleveland Orchestra and The Hallé, both conducted by the composer. Other highlights of 2024/25 include Verdi’s Requiem (Colorado Symphony Orchestra) and appearances with the New Jersey Symphony under Xian Zhang. She makes her debut with the Seattle Opera singing Anna in a concert version of Les Troyens, and later this month she will appear in recital for Chamber Music Detroit with composer and pianist Robert Spano, to be recorded for future release.

Recent concert highlights include Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony (Kansas City Symphony Orchestra) and his Third Symphony (San Francisco Symphony); John Adams’s El Niño (Houston Symphony); and a gala performance of Beethoven’s Ninth with the New York Philharmonic.

Sought after by many major composers, she has premiered works by John Corigliano, Kareem Roustom, Joby Talbot, and Bryce Dessner, including the title role in John Adams’s Gospel According to the Other Mary (written for her). She also created the role of Federico García Lorca in Osvaldo Golijov’s Ainadamar, which she reprised with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Robert Spano in concert and on a Grammy Award-winning Deutsche Grammophon recording.

Josh Lovell

Canadian tenor Josh Lovell performs in some of the world’s most prestigious houses in repertoire spanning the Baroque to the present day. In the 2024/25 season, he will return to Teatro alla Scala to sing Ritornello in Gassmann’s L’Opera seria, make his debut at the Rossini Opera Festival as Lindoro (The Italian Girl in Algiers), and appear with Oper Frankfurt as Grimoaldo (Rodelinda), and Atlanta Opera as Jupiter and Apollo (Semele). In addition to these concerts with the SLSO, he will make his debut with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Mozart’s Coronation Mass, and appear in his native British Columbia in a solo concert with the Victoria Symphony.

He recently made debuts at the Teatro alla Scala singing Ferdinand in The Tempest by Thomas Adès, and at the Glyndebourne Festival (Ernesto in Don Pasquale). His extensive experience on the opera stage also includes leading roles for Paris National Opera (Ferrando in Così fan tutte), Bavarian State Opera and Bolshoi Theater (Count Almaviva in The Barber of Seville), Oper Leipzig, Deutsche Oper Belin, Teatro Real, and Gran Teatre del Liceu, as well as a Vancouver Opera and Canadian Opera Company. A former member of the Vienna State Opera ensemble, his roles there included Ernesto, Don Ottavio (Don Giovanni), Don Ramiro (La Cenerentola), Nemorino (The Elixir of Love), Fenton (Falstaff), and Lysander (A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

In concert, he recently made his Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra debut in Rossini’s Petite messe solennelle. He has also sung Mozart with the Teatro Nacional de São Carlos in Lisbon, toured with Les Talens Lyriques and Christophe Rousset, sung Messiah with the North Carolina Symphony, and Peter in Handel’s Brockes Passion with The English Concert. Other concert highlights include Bach’s Coffee Cantata (Music of the Baroque), Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Sinfonietta Rīga), Mozart’s Requiem (Vancouver Symphony Orchestra), and concerts with the Vienna Philharmonic and Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg.

Dashon Burton

Three-time Grammy-winning bass-baritone Dashon Burton has built a vibrant career, performing regularly throughout the U.S. and Europe. He returns to the SLSO having most recently sung in Mozart’s Great C Major Mass in 2019/20. His engagements this season began with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at the Hollywood Bowl (Los Angeles Philharmonic conducted by Gustavo Dudamel). Other highlights for 2024/25 include a return to the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra for his second season as Artist-in-Residence, singing Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer and Bach’s ‘Ich habe genug’; his Boston Symphony Orchestra subscription debut singing Whitman Songs by Michael Tilson Thomas; and his Toronto Symphony Orchestra debut in Mozart’s Requiem. He will also sing Mozart’s Requiem with the Minnesota Orchestra and Thomas Søndergård; and Handel’s Messiah with the National Symphony Orchestra.

Last season, he collaborated frequently with Michael Tilson Thomas, including performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (San Francisco Symphony) and Copland’s Old American Songs (New World Symphony). He also sang Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (Washington Bach Consort) and Handel’s Messiah with both the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra, sang the title role in Sweeney Todd at Vanderbilt University, and appeared in a semi-staged production of Mozart’s Magic Flute (The Cleveland Orchestra).

In 2021, he earned his second Grammy Award (Best Classical Solo Vocal Album) for his role in Ethel Smyth’s The Prison with The Experiential Orchestra. This followed his 2013 Grammy for the debut album of Roomful of Teeth. In 2024, he earned his third Grammy for this groundbreaking ensemble’s latest recording, Rough Magic. His discography also includes Songs of Struggle and Redemption: We Shall Overcome; the Grammy-nominated recording of Paul Moravec’s Sanctuary Road; Holocaust, 1944 by Lori Laitman; The Listeners by Caroline Shaw (Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra), and a critically acclaimed album of spirituals.

Dashon Burton holds degrees from Oberlin College and Conservatory and Yale University’s Institute of Sacred Music. He is currently an assistant professor of voice at Vanderbilt University.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.