Mozart’s Journey (November 15–16, 2024)

Program

November 15–16, 2024

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Behzod Abdraimov, piano

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

- Symphony No. 1 in E-flat major, K.16

- Molto Allegro

Andante

Presto

- Molto Allegro

Mozart

- Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K.466

- Allegro

- Romance

- Allegro assai

Behzod Abduraimov, piano

Intermission

Mozart

- Overture to Mitridate, rè di Ponto

Anna Clyne (b. 1980)

- Within Her Arms

Mozart

- Symphony No. 31 in D major, K.297 (Paris)

- Allegro assai

Andante

Allegro

- Allegro assai

Mozart’s Journey

In tonight’s concert, Stéphane Denève takes us on a journey with Mozart. The “itinerary” is out of chronological order for musical reasons, but historically it takes us from London and Mozart’s earliest known symphony to Vienna and one of his most powerful and admired concertos.

London, 1764–65

The journey begins with the Mozart family on the road. Leopold Mozart—himself a composer and a well-known violinist—recognized the immense musical talent of his children—Maria Anna (“Nannerl”) and Wolfgang Amadeus, “the miracle that God allowed to be born in Salzburg”—and pinned his family’s hopes on his son finding a patron. In 1762, when Wolfgang was six, he took the children to Munich and Vienna, and they spent the following six or so years touring Europe as prodigies. It was a relentless schedule, arduous even by today’s standards, and as a result, the young Mozart was extraordinarily well-travelled at a time when only the very wealthy were free to be so mobile. The experience also brought the family in contact with Europe’s most influential figures. How many 18th-century composers could say they’d visited Versailles and sat on the knee of Marie-Antoinette?

The Mozarts’ travels eventually brought them to London via a turbulent Channel crossing, and there they stayed for 15 months. Both children performed for the royal family (George III and Queen Charlotte) and in public concerts, and Wolfgang found a friend and mentor in Johann Christian Bach, “the London Bach.” It was here that he began composing symphonies, learning his craft in London’s concert halls.

You might wonder how Leopold Mozart—a musical employee, effectively a servant, of the Prince-Archbishopric—was permitted to spend so much time away from Salzburg, or indeed how he could afford to do so. But his son was a celebrity, regarded as a cultural ambassador for his native city. As a result, Leopold was granted paid leave and financial assistance for the family’s travels, and in 1769 Wolfgang was even named “concertmaster” so that he might hold an official title (but not the salary).

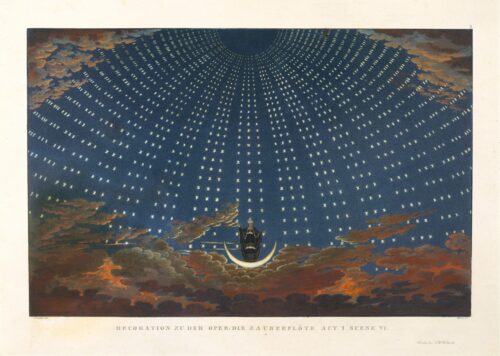

Milan, 1770

Newly promoted, Mozart set off with his father for Italy, the home of opera, where they were to spend most of the next four years. There, in Milan, the 14-year-old Mozart composed his fourth work for the stage and his first big opera, earning a fee not far shy of what established adult composers were receiving. Mitridate, rè di Ponto was a major achievement—six hours of richly scored music, including the ballet—and, despite his youth, Mozart was being taken seriously. The Gazetta di Milano reported: “The young maestro di cappella, who is not yet fifteen years of age, studies the beauties of nature and represents them adorned with the rarest musical graces.”

Salzburg kept Mozart busy but he found the city provincial and he chafed under the stern guardianship of his father. By his early 20s, he was searching for a post that would afford him independence and access to the kind of vibrant musical culture he’d witnessed in London and other cities as a child.

Paris, 1778

The job hunt took him to Paris via Augsburg and Mannheim (famous for its virtuoso orchestra), this time travelling with his adored mother, Maria Anna. In Mannheim he fell in love with Aloysia Weber and dallied there as long as he dared, but no post presented itself. In Paris it was the same story: performance opportunities, but not the security of a post or patronage.

He did, however, find musical satisfaction in the orchestra of the Concert Spirituel—a large and disciplined group of 65 musicians—and it was for this ensemble that his “Paris” Symphony was commissioned. We’re fortunate that Mozart composed this symphony away from home, because his delight in its creation and its eventual success is captured in the letters he wrote to his father in Salzburg. At first Mozart claims he doesn’t care whether the Parisian audience will like his new symphony or not, but it soon becomes obvious that this is just posturing: “I can answer for its pleasing the few intelligent French people who may be there—and as for the stupid ones, I shall not consider it a great misfortune if they are not pleased. I still hope, however, that even asses will find something in it to admire.”

He goes on to describe in some detail the various musical strategies he has adopted to satisfy (and surprise) French taste, and he reports with obvious pleasure the enthusiastic response. After the symphony, he writes, “out of pure joy I went right to the Palais Royal, ate a large ice, said the rosary I had promised, and went home.” Picture the 22-year-old composer: eating a celebratory ice cream (or perhaps a sorbet) in the gardens of the palace.

Bereavement, 1778 and 2008

But Mozart also had to write home with difficult news. His mother had fallen ill in May 1778, just two months after their arrival in Paris, and by the premiere of the symphony in June, she was too sick to attend the concert. On July 3 she died and was buried in the cemetery of Saint-Eustache; there was little for Mozart to do but return once more to Salzburg. It’s at this point that a living composer, Anna Clyne, enters the story. At first glance, she appears not to belong, but she too suffered the loss of a beloved mother. In 2008, news of her mother’s death inspired Within Her Arms, a powerful and haunting elegy for 15 strings.

Vienna, 1785

June 1781 was a turning point for Mozart. He finally engineered his own dismissal from Salzburg (he was literally booted from the room) and moved to Vienna, the musical heart of 18th-century Europe and his ultimate destination.In Vienna, Mozart married Aloysia’s sister Constanza—on the rebound as it were. He was still unable to secure a post that might support a family, but he was able to establish himself as a composer-virtuoso, with piano concertos as his calling cards. Central to his reputation were self-promoted subscription concerts or “academies,” which showed his talents before the widest possible audience, and by the time he premiered his D minor piano concerto (K.466) on February 11, 1785, Mozart, now 29, was approaching the height of his popularity and success. Mozart was home.

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

Symphony No. 1

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born 1756, Salzburg, Austria

Died 1791, Vienna, Austria

Mozart would have been eight years old when he composed his Symphony No. 1. The Mozart family was in London, and the symphony was almost certainly one of several performed in the concerts in which “all the Overtures” were of this “little Boy’s own Composition.” The billing of symphonies as “overtures” was not a printer’s error. The history of the symphony as a genre begins in the Italian opera house, where an evening of musical theatre would open with a sinfonia. The terms “overture” (from French) and “sinfonia” came to be used interchangeably, but amounted to the same thing: a short, three-movement work (fast—slow—fast) intended to command attention and quiet a rowdy audience.

By the time Johann Christian Bach and Karl Friedrich Abel were running their famed concert series in London in the late 18th century, the sinfonia, or overture, had taken on a life of its own as a concert genre, its newly emerging function the showcasing of an orchestra. Which is perhaps why the young Wolfgang asked his sister Nannerl to remind him to “give the horn something worthwhile to do!” As it turns out, there’s nothing showy for the horns in this symphony, but the slow four-note phrase they play in the opening minute of the second movement (Andante) is the earliest instance of an important motif that would turn up in later works, including Mozart’s last symphony, the “Jupiter” (K.551).

It would be unfair to compare this symphony to the “Jupiter,” but it is an impressive example of the symphonies that were being played at the Bach-Abel concerts, providing Mozart’s models. K.16 ticks every box in the “formula,” beginning with the fanfare-like opening of the first movement (Molto Allegro) that immediately drops to a quiet passage. (The “Paris” symphony offers the same trope in the hands of a mature composer.) Also ticking boxes are the lively passages for the strings, repeated notes for emphasis, and engaging expressive effects. For example, the stalking figure in the bass line of the slow movement (Andante), would not be out of place in an opera, says scholar Neil Zaslaw, “perhaps accompanying a nocturnal rendezvous.”

The autograph manuscript suggests that Leopold Mozart made adjustments to his son’s orchestration and other details, but the musical ideas are clearly Wolfgang’s own and show not only a command of harmony and form, but an inventiveness that’s already transcending formula.

| First performance | This symphony was completed towards the end of 1764 and probably first performed in the Mozarts’ public concert in London on February 21, 1765, at the Little Theatre, Haymarket. |

| First SLSO performance | January 31, 1953, Eleazar de Carvalho conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 13, 2013, Anthony Marwood conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 oboes, 2 horns, strings |

| Approximate duration | 13 minutes |

MOZART Piano Concerto No. 20

This is the only Mozart piano concerto that has never slipped in popularity. Beethoven played it in a 1795 concert to benefit the composer’s widow, and in the years that followed, the concerto was revered alongside Don Giovanni and the Requiem—dark, brooding passions and turbulent musical gestures being the key to the 19th-century imagination. Modern listeners continue to notice the theatrical drama and tension in the D minor concerto, but what Mozart’s father Leopold considered remarkable in 1785 was its artfulness, its delightful construction and its exceptional difficulty.

The turbulent opening of the first movement (Allegro) is inherently orchestral in character and quite unsuitable for the piano—Mozart sets the stage for a concerto in which the soloist and orchestra stand in contrast. Rather than compete with the dramatic gestures of the opening, the piano enters with its own theme, lyrical and pensive, and it’s only later that the soloist’s material is connected with that of the orchestra. With this concerto, Mozart was breaking new ground: not only his first concerto in a minor key but the first of what are sometimes described as his “symphonic concertos,” in which he gives more musical ideas to the orchestra, occasionally places the soloist in an accompanying role, and enriches the sound with trumpets and drums.

The second movement is a Romanze, a then fashionable genre, for which Mozart provides simple and genteel music, beginning with the piano unaccompanied. Drama returns in the middle, with a violent shift to a minor key and a return of the turbulence of the first movement.

The finale (Allegro assai) also begins with the piano alone, and this time it’s the soloist who has the “symphonic” gesture: a vigorous rising theme outlining a chord, suggestive of the thrilling “Mannheim rocket” so admired in orchestral music of the time. It’s enough to shatter the mood of the Romanze and launch us into one of Mozart’s few minor-key rondos. As in the first movement, powerful and typically “orchestral” ensemble passages are set against lyrical solo themes, which in turn allude to themes from the Allegro. The movement is full of ambiguities and quirks until the opportunity for a miniature improvised lead-in, or Eingang, brings about an abrupt, cheerful ending in D major.

| First performance | February 11, 1785, conducted from the piano by the composer at a self-promoted subscription concert in Vienna |

| First SLSO performance | January 25, 1918, with conductor Max Zach and soloist Ossip Gabrilowitsch |

| Most recent SLSO performance | September 29, 2017, David Robertson conducting with soloist Emanuel Ax |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 30 minutes |

MOZART Overture to Mitridate

Mithridates, King of Pontus was Mozart’s first “serious” opera, commissioned for Milan at the end of 1770. Mithridates was a historical character—a king defending his empire against the Romans—but the opera’s plot, based on a play by Jean-Baptiste Racine, is fiction. Its intricacies turn on rivalry in love, ambition, and the treachery of sons, and the drama concludes with Mithridates victorious in battle but mortally wounded.

The medley overture, introducing themes from the opera to follow, didn’t become common practice until the 19th century. Mozart was one of the first to attempt something like this, prefiguring the drama in his Don Giovanni overture in 1787. But when he wrote Mitridate as a 14 year old, he was following the conventions of 18th-century opera. The result is an overture in the form of a three-part sinfonia in the Italian style. Fast sections (an Allegro and an even quicker Presto) frame a slower section (Andante grazioso) in which the first flute contributes to the singing character and gracefulness of the music.

| First performance | December 26, 1770, at the Teatro Regio Ducale, Milan, directed by the composer |

| First SLSO performance | June 15, 1984, Gerard Schwarz conducted the complete opera with vocal soloists |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 horns, strings |

| Approximate duration | 6 minutes |

Within Her Arms

Anna Clyne

Born 1980, London, England

Within Her Arms is one of Anna Clyne’s most frequently performed orchestral works, with nearly 200 performances throughout the US, where she is based, and as far afield as Australia, as well as in her native Britain. It’s also her most personal creation. She was working on another “energetic, chaotic” piece for a commission in 2008 when she learned of the sudden death of her mother, Colleen Clyne. “I sat at the piano with a candle and a beautiful photo of her from that week,” she says. “And I just wrote this music over the course of the next 24 hours.”

The score is prefaced by a poem by Vietnamese monk and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh, from which the title is drawn:

Earth will keep you tight within her arms dear one—So that tomorrow you will be transformed into flowers—This flower smiling quietly in this morning field—This morning you will weep no more dear one—For we have gone through too deep a night.This morning, yes, this morning, I kneel down on the green grass—And I notice your presence.Flowers, that speak to me in silence.The message of love and understanding has indeed come.

(From “Message” in Call Me By My True Names, 1999, with permission of Parallax Press)

This is music to be seen and “felt” as well as heard. It’s scored for an ensemble of 15 string players, each playing their own part, and Clyne’s concern for the spatial qualities of her music is reflected in the way the musicians are positioned on the stage. The musical motifs “dance around the ensemble,” she explains, and she pays attention to the physicality of the musicians’ gestures—the energetic effect of an upbow, for example, or the shimmering effect that results when a string player bows close to the bridge (sul ponticello).

Born in London in 1980, Anna Clyne studied cello and completed her undergraduate degree at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Although she’d composed as a child, she began formal studies in composition relatively late, during a study-abroad year in Canada.

Her private creative process includes painting and movement, and some of her earliest works were composed for dance. Many of these combined acoustic instruments and electronics, and although Within Her Arms is completely acoustic, its sound world reflects that experience. For example, the music begins with a simple melody from a single violin, with the other violins sustaining the notes of the melody to create the illusion of ambient reverb. She also explores other “electronic” processes in her orchestration, for example, delay, reversing sounds, time expansion, and compression.

On the surface, Within Her Arms may seem relatively simple and meditative. But as music critic Alex Ross, one of her most ardent champions, points out, this “fragile elegy” rewards close listening. Its “intertwining voices of lament” bring to mind the English Renaissance masterpieces of Thomas Tallis and John Dowland, he says, while occasionally breaking down “into spells of static grief, with violins issuing broken cries over shuddering double-bass drones.”

| First performance | April 7, 2009, Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic |

| First SLSO performance | February 18, 2012 as the accompaniment to the ballet twice (once), choreographed by Terence Marling for the Hubbard Street Dance Company, conducted by David Robertson |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 8, 2021 in a streamed program conducted by Stéphane Denève |

| Instrumentation | 6 violins, 3 violas, 3 cellos, 3 double basses |

| Approximate duration | 14 minutes |

MOZART Symphony No. 31 (Paris)

This symphony was commissioned for the Concert Spirituel concert series while Mozart was visiting Paris in 1778. The nickname isn’t Mozart’s, but it’s entirely warranted, because nearly every aspect of the symphony shows Mozart exploiting the possibilities of the large Paris orchestra, and playing to the taste and expectations of his Parisian audience.

Since the orchestra had them, Mozart included clarinets for the first time in one of his symphonies. And since most symphonies in Paris at that time were composed in three movements, rather than four, he didn’t write a minuet movement. But the most striking aspect of the “Paris” symphony is the way Mozart sets out to please, and tease, his audience. He knew, for example, that the Parisians liked noisy symphonies, and the grandeur of the music is further emphasized by it being in D major—a key that’s friendly to trumpets and drums, and guaranteed to create a brilliant effect.

He also knew that the Parisians, proud of their disciplined violin sections, were fond of a gesture known as the premier coup d’archet (first stroke of the bow). He found this amusing: “What a fuss the oxen here make of this trick! The devil take me if I can see any difference! They all begin together, just as they do in other places.” But that didn’t stop him turning it to musical advantage. The symphony begins with all the strings playing the same notes in the same rhythm—four repeated notes and an upward scale—and Mozart repeats the gesture at various key moments, using it to draw the first movement (Allegro assai) together. At another point in the first movement he writes a passage that he knows the audience will probably applaud, and then brings it back at the end, twice, for added effect.

Mozart’s wicked sense of humor emerges in the last movement (Allegro). Observing that finales in Paris typically began with all the instruments playing together and in unison, he concocted a surprise: “I began mine with the two violin sections only, softly for the first eight measures—followed instantly by a forte! The audience, as I expected, said “Shh!” at the soft beginning, and as soon as they heard the forte began to clap their hands.”

The slow middle movement (Andante) had also pleased the audience, but Joseph Legros, the promoter of the concert, considered it too long and “full of strange modulations.” Mozart didn’t agree, but he obliged with a simpler piece, remarking that each was “appropriate in its own way.” He took the original slow movement home with him, leaving the shorter one in Paris with Legros, and it’s this longer Andante that’s nearly always performed today.

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

| First performance | June 18, 1778 (Corpus Christi) in Paris by the Concert Spirituel orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | December 13, 1964, Robert La Marchina conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 8, 2016, Nicholas McGegan conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 17 minutes |

Artists

Behzod Abduraimov

Pianist Behzod Abduraimov made his SLSO debut in the opening concerts of the 2018/19 season, playing the Grieg concerto. Born and raised in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, at the age of 15 he began studying with Stanislav Ioudenitch at the International Center for Music, Park University, where he is now Artist-in-Residence, and he came to international attention when he won the London International Piano Competition in 2009. Since then, he has performed with many of the world’s leading orchestras and conductors, and released several acclaimed recordings.

The 2024/25 season sees him performing with the Bamberger Symphoniker, Orquesta y Coro Nacionales de España, NDR Radiophilharmonie (Canary Islands Festival), Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, Sinfonieorchester Basel, and Berner Symphonieorchester, as well as the Singapore Symphony and Tokyo Philharmonic orchestras. In addition to the SLSO, his North American engagements include the Minnesota Orchestra and the Atlanta, Detroit, Toronto, and Vancouver symphony orchestras, and in August he marked the tenth anniversary of his Los Angeles Philharmonic debut. This month he makes two important recital debuts: Cal Performances in Berkeley and Walt Disney Concert Hall presented by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Highlights of previous seasons have included concerts with the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, NHK Symphony, Wiener Symphoniker, and Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin (RSB). His recital appearances include Carnegie Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, and he regularly performs in international festivals such as Aspen, La Roque Antheron, Lucerne, Ravello, Rheingau, and Verbier.

His recordings have won numerous awards including the Choc de Classica and Diapason Découverte, and his most recent release, Shadows of My Ancestors, featuring music by Ravel, Prokofiev, and Uzbek composer Dilorom Saidaminova, was a Gramophone Editor’s Choice and shortlisted for a Gramophone Award. His recitals have also been widely streamed, including on medici.tv, and his 2016 BBC Proms debut with the Munich Philharmonic was released on DVD.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.