An Evening with Yo-Yo Ma (May 3, 2024)

Program

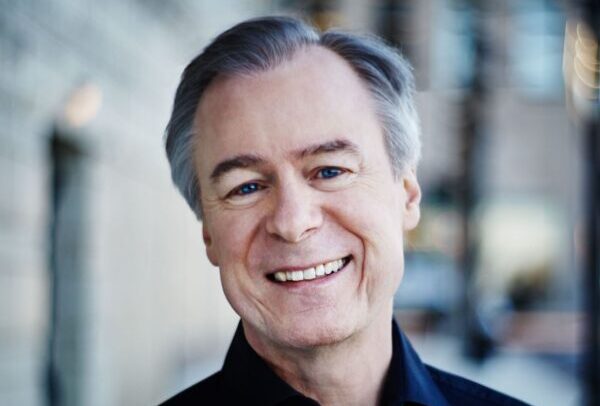

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Yo-Yo Ma, cello

Claude Debussy

La Mer

De l’aube à midi sur la mer

(From dawn to noon on the sea)

Jeux de vagues (Play of the waves)

Dialogue du vent et de la mer

(Dialogue of the wind and the sea)

Edward Elgar

- Cello Concerto in E minor, op. 85

- Adagio – Moderato –

- Lento – Allegro molto

- Adagio

- Allegro – Moderato – Allegro, ma non troppo

Yo-Yo Ma, cello

Performed without intermission

Program Notes

La Mer

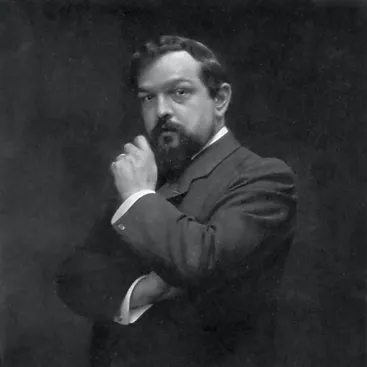

Claude Debussy

Born 1862, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Died 1918, Paris, France

Musical escape

In 1904, Claude Debussy was in pain. After he had left his unhappy second marriage, his wife threatened suicide and eventually shot herself, non-fatally. Debussy was cast adrift, deserted by friends and supporters, a shell of his former self.

“I’ve never been able to live in a world of real things and real people,” he wrote. “I have this insurmountable need to escape from myself in adventures which seem inexplicable because they reveal a man that no one knows.”

Debussy, as he so often did, escaped into music, and he escaped into memories of the sea. He’d once said that if he hadn’t been a musician he would have become a sailor; on another occasion he’d persuaded a ship’s captain to take him out in a fierce storm. For Debussy, the ocean retained its power, both beautiful and terrifying.

What’s in a title?

La mer (The Sea) is subtitled “trois esquisses symphoniques” (three symphonic sketches). Debussy chose these words carefully. Fearing that the word “symphony” would align him with a reviled conservative culture, he instead adopted the word “sketches.” Sketches: musical drawings. Sketches: forms that are outlined, preliminary.

At the same time, despite the implied imagery of Debussy’s movement titles, don’t expect the “Mickey Mousing” of film soundtracks or even program music in the 19th-century sense. Debussy’s intent is more evocative, more fluid—suggesting the idea of the sea rather than a literal depiction.

“I feel more and more that music,” he wrote, “is not something that can flow inside a rigorous, traditional form.” The sounds of La Mer flow like ocean waters: sometimes still, sometimes storm-tossed, sometimes forming recognizable shapes, sometimes slipping from our grasp.

Sketchbook or symphony?

And yet, despite the composer’s assertions and the evocative character of the music, La mer can also be heard as a symphony. (Some think it’s the best symphony ever written by a French composer.)

It begins with a carefully worked out opening movement that might not obey the “rules” of classical form on the surface but feels like it does because of what’s going on in the harmony underneath. There is a playful and inventive second movement that can easily pass as a symphonic scherzo. And the third movement provides a satisfying “big finish.”

The view from the shore

La Mer is popular today because it combines the exciting climaxes and satisfying contrasts we enjoy in Romantic symphonic music with Debussy’s magical and “impressionistic” colors and textures. But the new musical world of La Mer confounded many listeners in 1905. (And in 1907 when the work reached the United States). Debussy dismissed the criticisms of those who “love and defend traditions which, for me, no longer exist. [Such traditions] were not all as fine and valuable as people make out. [T]he dust of the past is not always respectable.”

Navigating the music

Debussy is a sonic magician—conjuring whole worlds that might be gone in an instant. A trumpet and an English horn produce new colors through alchemy. Clarinet and flute play hide-and-seek amid plucked violas. In the first movement, cellos (divided into four groups) soar through the air, leaving French horn contrails.

Each movement takes a journey that is unpredictable, yet feels organic:

1. De l’aube à midi sur la mer (From dawn to noon on the sea)

This movement glows and flutters, ending with an overwhelming surge. The famous tongue-in-cheek compliment from fellow composer Erik Satie is a reminder not to take any of these titles too literally: he told Debussy that he was especially fascinated by the moment “between half past ten and a quarter to eleven.”

2. Jeux de vagues (Play of the waves)

Slippery melodies dart and weave around the orchestra. The whimsically spinning musical ideas have been compared to arabesques flowing from the brush of an Art Nouveau or Impressionist painter.

3. Dialogue du vent et de la mer (Dialogue of the wind and the sea)

Listen for motifs from the previous two movements as the music builds the dialogue of the title. The woodwinds are, of course, the wind; the lower strings are a very choppy sea. The movement is wild, violent, barely able to contain its radiant, hymn-like conclusion.

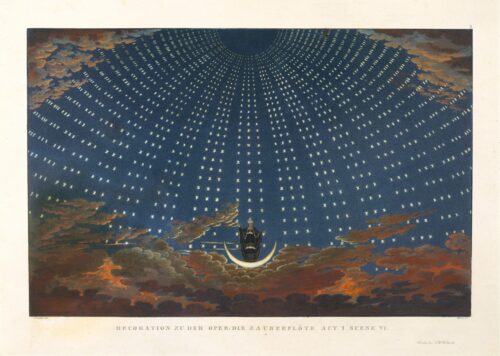

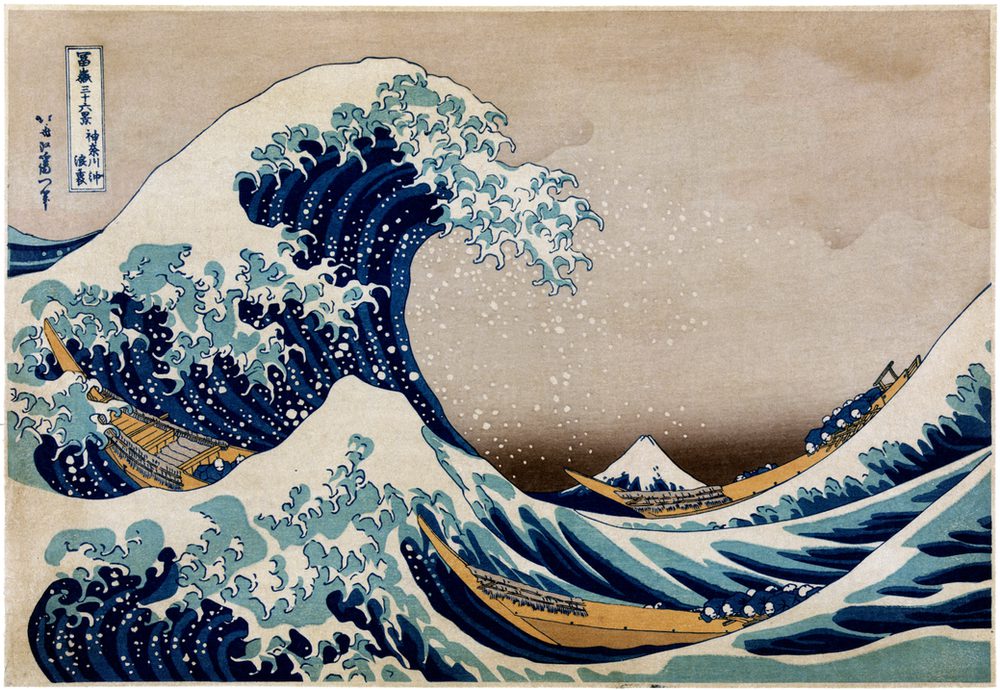

The art of La Mer

—Debussy to his stepson, 1906Music has this over painting…it can bring together all manner of variations of color and light.

Debussy’s influences included the crazy perspectives and double focuses of the English painter William Turner, as well as the clarity of form in the work of 19th-century Japanese artists Hiroshige and Hokusai. Debussy admired Hokusai’s woodcut The Great Wave off Kanagawa so much that he chose it for the cover of La Mer when it was published.

Adapted from a note by Tim Munro © 2019

| First performance | October 15, 1905 in Paris, Camille Chevillard conducting the Orchestre Lamoureux |

| First SLSO performance | January 23, 1914, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | September 22, 2019, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 2 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, 2 harps, strings |

| Approximate duration | 25 minutes |

Cello Concerto

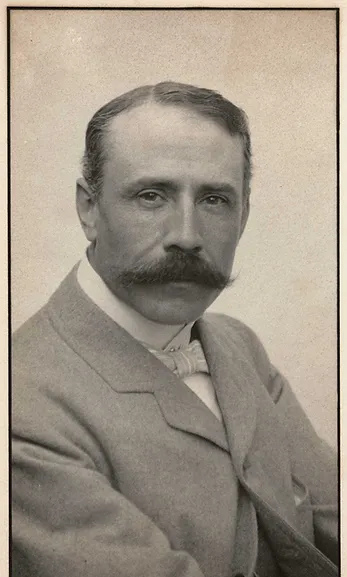

Edward Elgar

Born 1857, Broadheath, England

Died 1934, Worcester, England

Attitude to life

Edward Elgar once described the “meaning” of his cello concerto as “A man’s attitude to life.” This statement reveals little by itself; any individual’s outlook will, of course, depend on their experiences and circumstances in the world. But Elgar’s, at the time he wrote this work, were less than happy, and his elusive characterization of the concerto may well have been his way of hinting, however obliquely, at the bitterness and disillusion that were overtaking him in the autumn of his life.

This was, in a sense, the best of times and the worst of times for the composer. Now past 60, he could take satisfaction in his accomplishments and well-deserved recognition. Just 20 years earlier, his Enigma Variations had established him as the first English composer of international standing since George Frideric Handel. Yet this recognition had come only after years of obscurity and discouragement, and it brought relatively little in the way of material reward.

Worries over his finances and health plagued Elgar throughout World War I, and he composed little of consequence during those years. The war depressed him greatly, and even the signing of the Armistice, in November 1918, did little to raise his spirits. Still, life was not entirely bleak. Before the end of the war, Elgar had moved with his wife to a peaceful country house, and the proximity to nature cheered him considerably. Here at last he began to compose again, completing several pieces of chamber music in 1918. The following June he told a friend:

Elgar finished the concerto during the summer of 1919, and it was first performed in October in London. Audience and critical response was cool, partly due to a poorly rehearsed performance, but also because the concerto sounded so unlike Elgar’s pre-war music. Works such as the Enigma Variations and the Pomp and Circumstance Marches were extrovert and social in spirit, but the tone of the Cello Concerto is one of solitary and at times quite somber meditation.

Listening to the concerto

The Cello Concerto’s first audiences considered the music too frugal, too terse. It subsequently came to be regarded as opulent and emotional—partly due to the influence of Jacqueline du Pré’s recording. But the truth is closer to what the original listeners experienced, with Elgar avoiding any hint of sentimentality. In the words of conductor Adrian Boult, Elgar had “struck a new kind of music, with a more economical line, terser in every way.”

Even in its most lyrical moments, this is music with a rhetorical impulse. Elgar signals this by beginning with the soloist—the orator—and with recitative or “speech in music” rather than a big tune. This recitative (Adagio) is marked with Elgar’s favorite expression word—nobilmente (nobly)—and it sets the tone for the whole work as well as tying it together thematically.

Unusually for a concerto, the work is organized in four movements, although to the ear it may sound like three, since the first two movements are played without pause. After the opening recitative, the violas pick up the cello’s last note and begin the gentle, ambling theme (Moderato) that was Elgar’s very first idea for the concerto and which provides the key to his style in this work—moving easily through a new landscape of musical gestures.

The soloist’s opening recitative returns to mark the beginning of the second movement (Lento – Moderato), this time played with plucked strings (pizzicato) rather than the bow. This movement fulfills the role of a “scherzo” but its character is nervous and erratic rather than playful or joking.

As in a great speech, Elgar wants to reach us on an emotional level, not simply win an argument, and the third movement (Adagio) is where the concerto’s emotional message emerges with greatest intensity. It’s also—significantly—the most economical of the movements.

By contrast, the final movement seems expansive and relatively uncomplicated, although there remains an undercurrent of nostalgia and leave-taking. Fragments of themes and gestures from previous movements return and the recitative makes a final appearance in its original form towards the end. Throughout, the cello-as-orator “speaks” to us of regret and nostalgia, of sweetness and passion, of resolution and the intensity of life, and above all, of nobility tinged with sadness.

The Cello Concerto has an “end-of-life” character to it and Elgar wrote on the score “Finis. RIP.” This would prove to be his final orchestral work, yet it’s eloquent and powerful music from a composer who may have been feeling the weariness of age but who was also exploring a fresh voice.

Adapted from notes by Paul Schiavo © 2009 (Attitude) and Yvonne Frindle © 2014 (Listening)

| First performance | October 27, 1919, the composer conducting the London Symphony Orchestra with soloist Felix Salmond |

| First SLSO performance | January 19, 1934, Vladimir Golschmann conducting, Max Steindel as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 8, 2009, Christopher Seaman conducting, Daniel Lee as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo cello, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 30 minutes |

Yo-Yo Ma

Artist

Yo-Yo Ma’s multi-faceted career is testament to his belief in culture’s power to generate trust and understanding. Whether performing new or familiar works for cello, bringing communities together to explore culture’s role in society, or engaging unexpected musical forms, he strives to foster connections that stimulate the imagination and reinforce our humanity.

Most recently, he began Our Common Nature, a cultural journey to celebrate the ways that nature can reunite us in pursuit of a shared future. Our Common Nature follows the Bach Project, a 36-community, six-continent tour of J.S. Bach’s cello suites paired with local cultural programming. Both endeavors reflect his lifelong commitment to stretching the boundaries of genre and tradition to understand how music helps us to imagine and build a stronger society.

Yo-Yo Ma is an advocate for a future guided by humanity, trust, and understanding. Among his many roles, he is a United Nations Messenger of Peace, the first artist ever appointed to the World Economic Forum’s board of trustees, a member of the board of Nia Tero, the US-based nonprofit working in solidarity with Indigenous peoples and movements worldwide, and the founder of the global music collective Silkroad.

His discography of more than 120 albums (including 19 Grammy Award winners) ranges from iconic renditions of the Western classical canon to recordings that defy categorization, such as Hush with Bobby McFerrin and Goat Rodeo Sessions with Stuart Duncan, Edgar Meyer, and Chris Thile. Recent releases include Six Evolutions, his third recording of Bach’s cello suites, and Songs of Comfort and Hope, created and recorded with pianist Kathryn Stott in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. His latest album, Beethoven for Three, featuring a piano trio arrangement of ROMAN together with the “Archduke” Trio, op. 97, is the third in a new series of Beethoven recordings with pianist Emanuel Ax and violinist Leonidas Kavakos.

Yo-Yo Ma was born in 1955 to Chinese parents living in Paris. He began studying the cello with his father at age four and three years later moved with his family to New York City, where he continued his cello studies at the Juilliard School before pursuing a liberal arts education at Harvard. He has received numerous awards, including the Avery Fisher Prize (1978), National Medal of the Arts (2001), Presidential Medal of Freedom (2010), Kennedy Center Honors (2011), Polar Music Prize (2012), and Birgit Nilsson Prize (2022). He has performed for nine American presidents, most recently on the occasion of President Biden’s inauguration.

Yo-Yo Ma and his wife have two children. He plays three instruments: a 2003 cello made by Moes & Moes, a 1733 Montagnana cello from Venice, and the 1712 “Davidoff” Stradivarius.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.