Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto (March 22-23, 2024)

Program

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Tom Borrow, piano

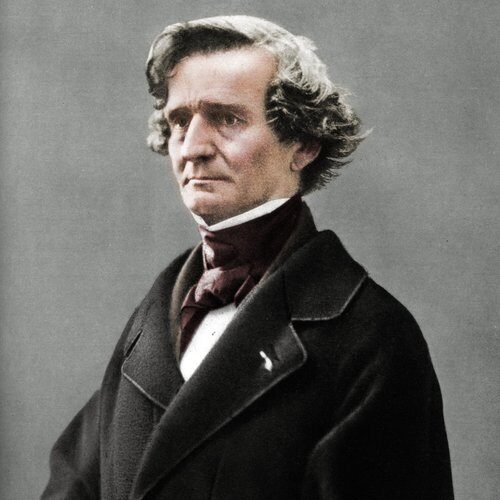

Hector Berlioz

Overture to Béatrice et Bénédict

Julia Wolfe

Pretty (First SLSO performances*)

Intermission

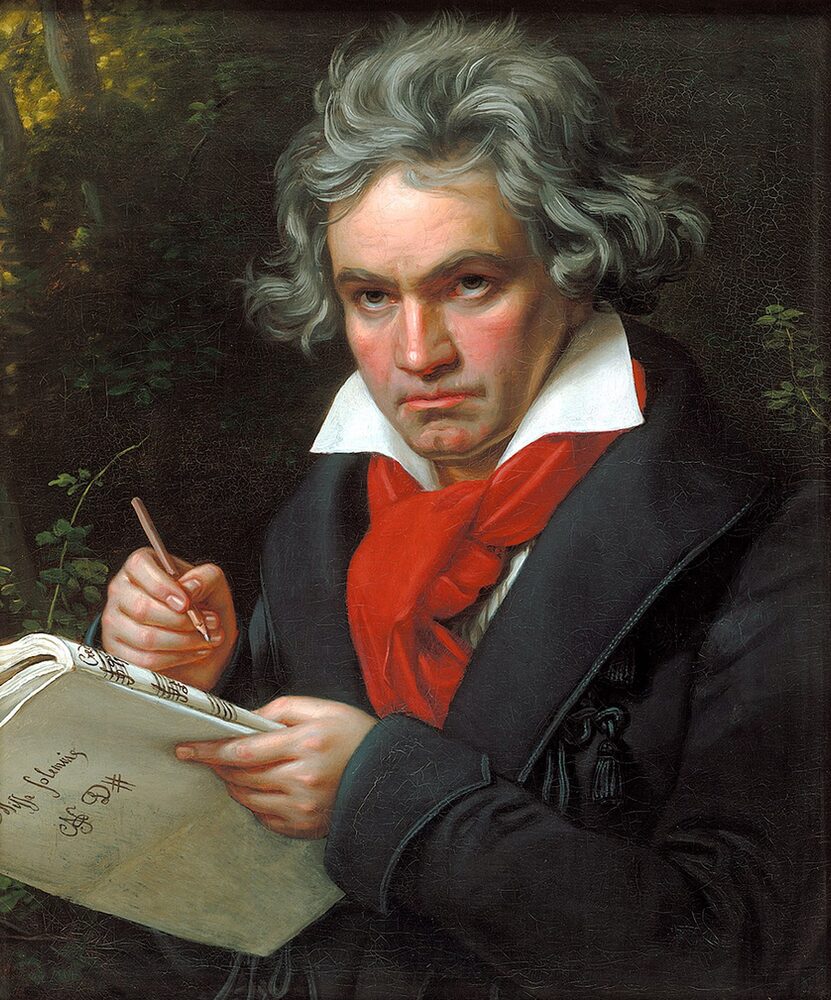

Ludwig van Beethoven

- Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, op. 73, “Emperor”

- Allegro

- Adagio un poco mosso –

- Rondo (Allegro)

Tom Borrow, piano

*Pretty was commissioned by the Berlin Philharmonic, Houston Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, and St. Louis Symphony Orchestra

Program Notes

Music as an art form can dispense with words without losing one jot of its power. A “Fifth Symphony” (choose your composer) can evoke strong emotion and take you on what feels like a journey. It might inspire plenty of words, but it doesn’t need them.

In this concert, however, words are everything. Hector Berlioz—not just a composer but one of the pioneering music critics of 19th-century France—fell in love with the drama and poetry of Shakespeare, despite having barely any English. He spent three decades taking inspiration from the Bard, and his final opera, Béatrice et Bénédict, represents the summit of his achievement, capturing to perfection the “merry war” between these two lovers from Much Ado About Nothing. The overture offers the world of the opera in microcosm and makes for an ideal beginning, whether in the theater or the concert hall.

From a work of literature we shift to the inspiration of a single, loaded word—“pretty”—and an exhilarating new piece by Julia Wolfe that asks plenty of questions. And after intermission, an otherwise “abstract” work—a piano concerto—comes to us with a word firmly attached. Never mind that “Emperor” isn’t Beethoven’s title, nor did he approve it, his Fifth Piano Concerto conveys all the magnificence and splendor the nickname suggests. But it does so much more. The power of Beethoven’s music lies in its combination of intensity and expression, scale and delicacy. No words required.

Overture to Béatrice et Bénédict

Hector Berlioz

Born 1803, La Côte-Saint-André, France

Died 1869, Paris

Shakespeare fandom hit the young Hector Berlioz like a lightning bolt, what the French call a coup de foudre. In his irresistibly juicy Mémoires, the composer describes his first encounter with the playwright in 1827, after an English touring company brought several of the plays to the Odéon in Paris. Shakespeare, Berlioz explains, was “then entirely unknown in France.” Never mind that Berlioz didn’t speak English, and the only available French translation was clumsy and imprecise; his experience of the poetry was transformative:

Berlioz’s romance with the Irish-born actress was doomed to burn out, but his love of the Bard endured. Over more than 30 years, Berlioz composed many works inspired by Shakespeare, including an early concert overture inspired by King Lear (1831), the remarkable “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette (1839), the orchestral song La Mort d’Ophélie (1842), and a funeral march for the last scene of Hamlet (1844). His last major work, the opera Béatrice et Bénédict, was a radically streamlined version of Much Ado About Nothing. Although he’d come up with the idea of setting this comedy to music not long after meeting Smithson, he didn’t begin working on it in earnest until 1860. Two years later, the opera premiered to acclaim in Germany—the only opera of his to achieve real success during his lifetime—and Berlioz himself declared it “one of the most lively and original things I have done.” Even so, it wasn’t produced in France until after the composer’s death, and today it is the overture that is heard most often.

The overture was completed last, enabling Berlioz to weave together at least six distinct arias and ensembles from the opera, beginning in the thick of the action with a whirlwind opening. It’s easy to hear echoes of the title characters’ witty sparring in the musical ideas that the orchestra tosses back and forth. This opening, with its nimble triplets, resolves to a limpid and spellbound theme based on a duet in which the quarreling pair admit that love has broken down their defenses: “a flame, a will o’ the wisp, coming from no one knows where, gleaming and vanishing to distract our souls.” Finally, as swirling melodies converge in a series of dramatic crescendos, the overture hurtles to a sudden stop: a fitting end to the opera Berlioz described as “a caprice written with the point of a needle.”

Adapted from a note by René Spencer Saller © 2016

| First performance | August 9, 1862, at the Theater Baden-Baden, the composer conducting |

| First SLSO performance | March 23, 1978, Leonard Slatkin conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 20, 2016, David Robertson conducting |

| Instrumentation | flute, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, cornet, 3 trombones, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

Pretty

Julia Wolfe

Born 1958, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

By her own account, Julia Wolfe “doesn’t write pretty.” In fact, the style of this Pulitzer Prize-winning composer is distinguished by an intense physicality and relentless power. Her music pushes performers to extremes and demands attention from her listeners. The work you’ll hear in this concert begins with relentlessly driving music and an instruction to play “strong, like sawing, raw, folk-like”—setting the scene for the next 20 minutes.

The word “folk-like” is key, giving us an orchestra of fiddlers and revealing some of Wolfe’s musical origins. Ahead of the premiere with the Berlin Philharmonic last year, she explained her deep connections to American folk music. Growing up in a small town near Philadelphia, she played fiddle, mountain dulcimer, and wooden bones. But she was also a child of rock and roll who also studied classical piano. “For me there are no musical hierarchies,” she said in an interview. “I like many types of music and the influences come from everywhere.”

At the same time, Wolfe considers herself an “American voice” in the tradition of Aaron Copland, as well as more recent composers: Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, and John Adams. In her review of the Berlin premiere of Pretty, Shirley Apthorp summed up Wolfe’s musical language as the “minimalist soundscapes of Steve Reich meet the animation of John Adams in a sound-world that is very much Wolfe’s own, a brash New York in-your-face yelp of delight.”

This introduces another key influence: Wolfe has spent most of her life in New York City, “a city of overwhelming power and creativity,” where she is also co-founder and co-artistic director of the legendary music collective Bang on a Can. As she explains, “I have one foot in the down-to-earth small town and the other in the universe of New York, where everyone comes who has big plans. My style is the same: a conglomerate, a mishmash.”

And so she draws inspiration from folk, classical and rock—all of which you’ll hear in abundance in Pretty. Look for the drum kit (not normally seen in a symphony orchestra). Listen for the strident pulsing of the brass instruments, the strings emulating electric guitars, and the wild sliding between notes that suggests the Doppler effect of approaching and retreating sirens. Feel the visceral energy and hypnotic rhythms. Allow the sudden pauses to catch you by surprise and make you think.

Wolfe isn’t afraid to be provocative or political. In 2019, the New York Philharmonic premiered Fire in My Mouth, a large-scale work for orchestra and women’s chorus inspired by American labor history and the women in New York’s garment industry at the beginning of the 20th century. And her titles catch the eye as readily as her music catches the ear: Window of Vulnerability, Her Story, Big Beautiful Dark and Scary, Cruel Sister…

Pretty is no exception—its title is a subversive dig at our expectations and assumptions. As Wolfe explains, the word “pretty” has had a complicated relationship to women. “If you go back to its Old English origins, you find it once meant ‘cunning, crafty, clever.’” (That sense survives in the related word “pert.”) Then the word morphed, as language does, and by the middle of the 15th century it had arrived at its current meaning. The implication, says Wolfe, is “more or less attractive but without any rough edges, without power of strength. And serving as a measure of worth in strange, limited, and destructive ways.” With this work then, she says, “Maybe we have a new kind of ‘pretty’ today.”

The result is bold—unafraid of noise, power, and aggression—and, writes Apthorp, “relentlessly ebullient,” while also finding space for delicacy. “I think music is a good way to question our ideas about the world,” says Wolfe, “ and to express where we are right now.” And so this intensely powerful work, “asks questions about how we view women today and perceive their voices.” What is pretty after all?

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

This note draws in part on an interview with Kerstin Glasow, published by the Berlin Philharmonic, as well as Julia Wolfe’s on-stage conversation with conductor Kirill Petrenko.

| First performance | June 8, 2023, Kirill Petrenko conducting the Berlin Philharmonic; the Houston Symphony gave the U.S. premiere on November 18, 2023, conducted by Juraj Valčuha |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (2nd doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 2 trumpets, trombone, bass trombone, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 20 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 5 “Emperor”

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born 1770, Bonn, Germany

Died 1827, Vienna, Austria

The title “Emperor,” by which Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto has been known since the early 19th century, possibly derives from one of the many apocryphal anecdotes that have come to us concerning the composer. According to this story, a French army officer stationed in Vienna attended the first performance of the concerto in the Austrian capital and was so moved by the grandeur of Beethoven’s music that he cried out: “C’est l’Empereur!” (It is the Emperor). Another, more likely, explanation is that it was coined by the English pianist and publisher Johann Baptist Cramer, which would explain why it caught on in English-speaking countries but not German-speaking ones and was likely unknown to Beethoven.

Even if he had been aware of the nickname, Beethoven would not have been flattered by the comparison with Napoleon. Once an ardent admirer of Bonaparte, he had become bitterly disenchanted as the French ruler revealed his ambition. The most famous evidence of this change of heart is the account of how, after hearing that Napoleon had assumed the throne, Beethoven scratched out the title of his third symphony, replacing “Buonapart” with the anonymous Sinfonia eroica (“Heroic Symphony”).

But despite its hazy origins, “Emperor” does not seem an inappropriate title. In 1809, when it was composed, this work far surpassed any and all other concertos in its expression of majesty and heroism, and it retains an imperious position among piano concertos even today.

Beethoven establishes the lordly character of the “Emperor” Concerto with an innovative opening, in which three sonorous orchestral chords each give way to cadenza-like flourishes from the piano. This serves as a prelude to the usual orchestral opening, one of the grandest and longest in any concerto. The tone established here places the music in the Classical-period tradition of concerto openings in a quasi-martial character. Such “military” openings, with their march themes and proud bearing, are found in a number of Mozart’s keyboard concertos, as well as Beethoven’s own early Piano Concerto in C major (op. 15).

When the piano rejoins the proceedings, it is as a member of a thoughtfully integrated ensemble rather than merely an exalted soloist. Far from being merely a virtuoso display piece, the piano concerto had acquired an almost symphonic character in Beethoven’s mind. The prominence the orchestra enjoys throughout this first movement is virtually unparalleled in the concerto literature. Beethoven has introduced an equitable balance between soloist and ensemble.

Also unparalleled was Beethoven’s handling of the solo cadenza. This was the first concerto in which the first-movement cadenza—traditionally improvised by the soloist—was written out in full. Beethoven would have had the integrity of the music in mind, but there was another, entirely pragmatic, motivation: this was the first of his piano concertos that he had been unable to introduce to the world himself—his deafness making public performance impossible. And so he wrote out a brief, integrated cadenza that echoed the magisterial flourishes from the opening, adding a stern instruction for the soloist: “Non si fa una Cadenza, ma s’attacca subito il seguente.” (Do not make up a cadenza, but go straight on to what follows.) This proved to be an influential move—in all the major concertos since, only one (Brahms’s Violin Concerto) has invited the soloist to provide their own cadenza.

The slow second movement (Adagio) is a serene and deeply devout meditation, one of Beethoven’s most beautiful and tender creations. It concludes with a final musing by the piano that evolves magically into the principal theme of the third movement (Allegro). After the militaristic first movement and the profound serenity of the second, this rondo-finale with its dance-like recurring theme brings emotional relief with a mood of irrepressible joy.

Adapted from notes by Paul Schiavo © 2014 and Yvonne Frindle

| First performance | November 28, 1811, Johann Schultz conducting the Leipzig Gewandaus Orchestra, Friedrich Schneider as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | November 14, 1913, Max Zach conducting, Wilhelm Backhaus as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | November 27, 2016, Robert Spano conducting, Stephen Hough as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 38 minutes |

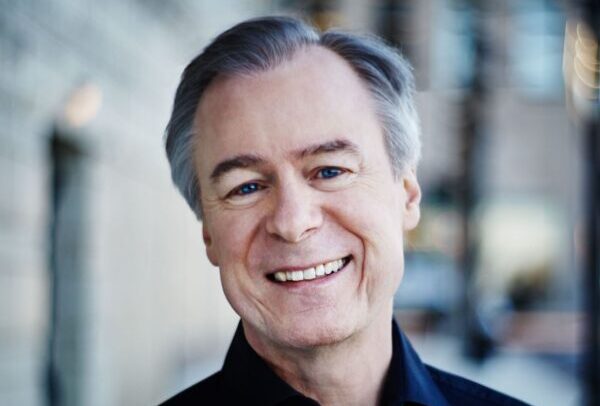

Artist

Tom Borrow

In 2019, Tom Borrow was called on to replace pianist Khatia Buniatishvili in a series of concerts with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. With just 36 hours’ notice, he performed Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G to public and critical acclaim. Following this success, he returned to the Israel Philharmonic for gala concerts in London and Mexico City and a second subscription series. In 2021 he made his U.S. debut, performing with the Cleveland Orchestra; this has been followed by engagements with the Baltimore and Atlanta symphony orchestras and these are his first concerts with the SLSO, as well as opening the 2023/24 season for Cal Performances (California).

As a BBC New Generation Artist (2021–23), he performed with all the BBC orchestras and in recital at Wigmore Hall, and in 2022 made his BBC Proms debut, performing at the Royal Albert Hall with the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Born in Tel Aviv in 2000, Borrow began studying piano at age five and he is currently a student of Tomer Lev of the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music, Tel Aviv University. He has been mentored by Murray Perahia and participated in masterclasses with artists such as András Schiff, Christoph Eschenbach, Richard Goode, Menahem Pressler, and Tatiana Zelikman.

In addition to appearing as a soloist with all the major orchestras of his native country, he has won every national piano competition in Israel, and in 2018 he received the Maurice M. Clairmont Award, given to a promising artist every two years by the America-Israel Cultural Foundation and Tel-Aviv University. In other career highlights, WWFM The Classical Network has featured him as an outstanding young talent, Interlude magazine named him Artist of the Month in 2021, and a number of his performances have been streamed and broadcast in Europe and internationally.

Equally in demand as a chamber musician and recitalist, he has performed in major venues such as the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Wigmore Hall, Berlin Konzerthaus, and Alte Oper Frankfurt, and has appeared for the Verbier Festival, Ruhr Piano Festival, Festival Piano Aux Jacobins (Toulouse), Aldeburgh Festival, Cheltenham Festival, Vancouver Recital Society, and Bolzano Concert Society (Italy).

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.