Sibelius’ Fifth (November 22 & 24, 2024)

Program

November 22 & 24, 2024

Jonathon Heyward, conductor

Yeol Eum Son, piano

William Grant Still (1895–1978)

- Threnody: In Memory of Jean Sibelius

Sergei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16

- Andantino – Allegretto – Tempo I

Scherzo (Vivace)

Intermezzo (Allegretto moderato)

Finale (Allegro tempestuoso)

- Andantino – Allegretto – Tempo I

Yeol Eum Son, piano

Intermission

Jean Sibelius (b. 1959)

- Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 82

- Tempo molto moderato – Allegro moderato –

Vivace molto – Presto

Andante mosso, quasi allegretto

Allegro molto – Misterioso – Largamente assai

- Tempo molto moderato – Allegro moderato –

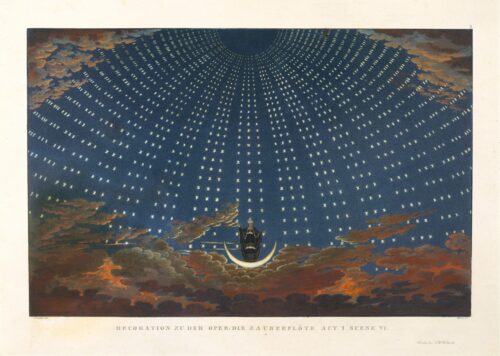

At the Edge of Heaven

While working on his Fifth Symphony, in April 1915, Jean Sibelius made a now-famous observation in his journal: “It was as if God the Father was throwing pieces of mosaic from the edge of heaven and asking me to figure out what the pattern was.” He was to obsess over this heavenly challenge for years, continuing to revise the symphony after its premiere, and the magnificent result really does come across as a kind of “deconstructed” symphony—playing with form in ways that might defy traditional analysis but which move the soul. The Fifth is easily Sibelius’s most accessible symphony, with memorable ideas and a directness of expression that’s optimistic and heroic in spirit.

After World War I, in far-off Harlem, the young William Grant Still found inspiration in the vision of nationhood and identity expressed in the Finnish composer’s music. So it’s perhaps no surprise that Still’s Threnody, composed in memory of Sibelius in 1965, begins with an uplifting brass gesture reminiscent of the older composer’s Finlandia. The “song of lamentation” that follows is richly scored, and noble and melancholy in tone rather than despairing—a fitting tribute for an admired composer on the centenary of his birth.

Still’s Threnody is the creation of a 70-year-old composer at the end of his career. The Prokofiev piano concerto in today’s program is the work of a young man: brashly taking delight in provoking his audience. It’s only two years older than the Sibelius symphony but very different in its outlook.

Both concerto and symphony have this in common, however: they are full of the composers’ “signature” musical gestures that we’ve come to

recognize and love.”

Threnody: In Memory of Jean Sibelius

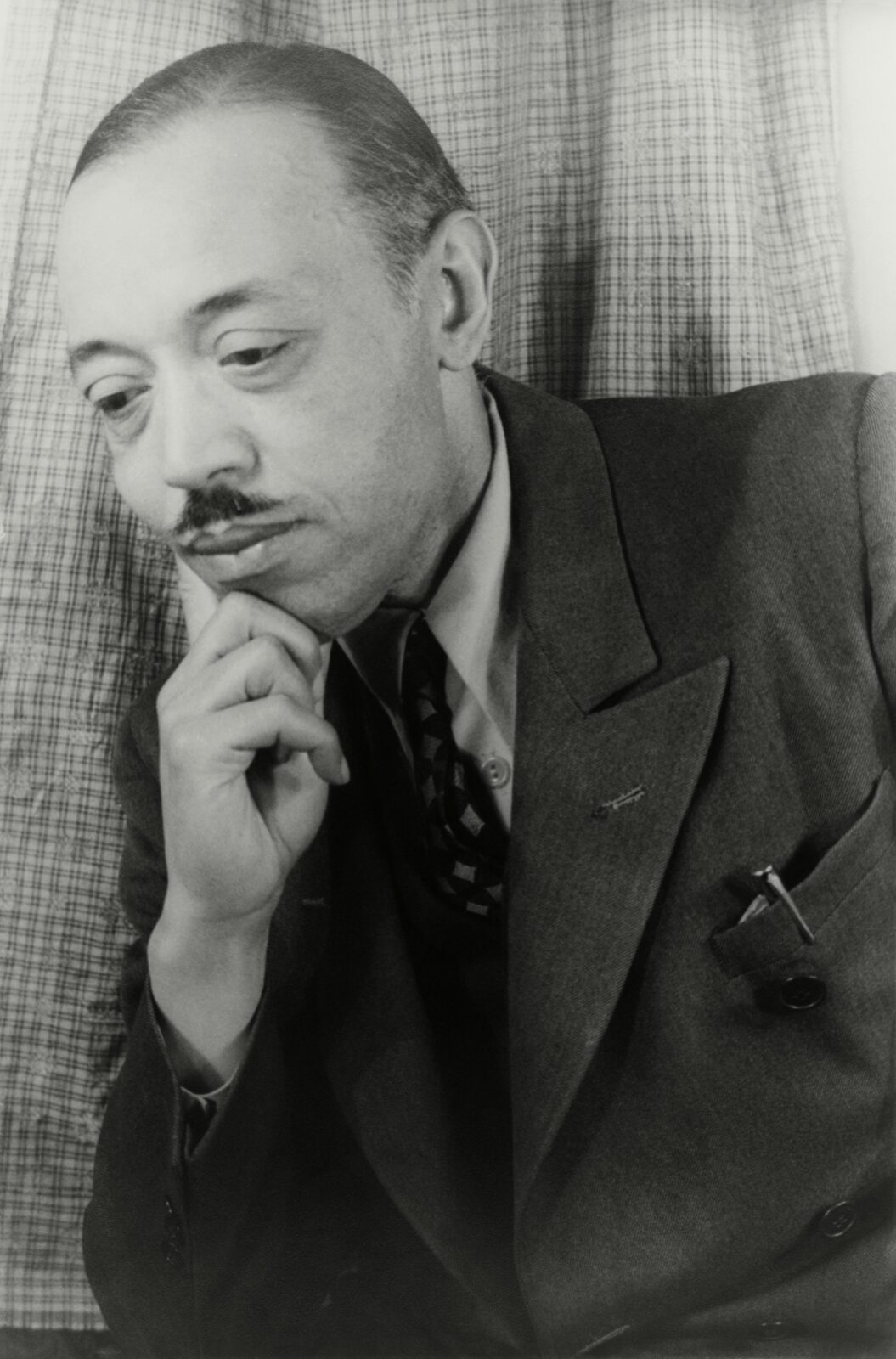

William Grant Still

Born 1895, Woodville, Mississippi

Died 1978, Los Angeles, California

The Threnody: In Memory of Jean Sibelius was one of William Grant Still’s last orchestral works, landing at the end of a long career that spanned a period of momentous social and musical change in the United States. Still was born in 1895, one year before the Supreme Court upheld Jim Crow in the landmark Plessy v. Ferguson decision, and he wrote the Threnody one year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ended legal segregation.

Still began his career writing parlor music for W.C. Handy in the mid-1910s, arranged music for radio shows in the ’20s, and worked as a Hollywood composer and orchestrator in the ’30s. After that, he focused on music for the concert hall and opera stage. His Afro-American Symphony (1930) was the first symphony by a Black composer to be performed by a major American orchestra, and he became the first Black conductor to lead a major American orchestra when he made his debut with the Los Angeles Philharmonic at the Hollywood Bowl in 1936. Altogether, he wrote eight operas and five symphonies. Still divided his output into three stylistic periods: “ultramodern” (influenced by his avant-garde teacher Edgard Varèse), “racial” (incorporating African American blues, jazz, and spirituals), and “universal,” from which the Threnody comes.

Listeners are sometimes surprised to see that Jean Sibelius (1865–1957), essentially a late-Romantic composer, lived well into the 20th century, several years beyond Sergei Prokofiev and even modernist icons such as Arnold Schoenberg and Charles Ives. The seeming anachronism arises in part because Sibelius, though long-lived, suffered from depression and alcoholism, and composed almost nothing after 1926—an infamous creative block that became known as “the silence from Järvenpää” (the Helsinki suburb where he resided).

Sibelius and Still never met, but Still’s second wife, Verna Arvey, recounts in a memoir that Sibelius once praised a recording of the Afro-American Symphony, recognizing that Still “had something to say.” And as Still strove to write more “universal” music, he may have seen a parallel in Sibelius, who started out as a path-breaking Finnish nationalist, writing politically conscious pieces based in local folklore, before becoming a more abstract symphonist.

In any case, the idea to memorialize Sibelius on his 1965 centenary was suggested by the conductor Fabien Sevitzky, and the University of Miami commissioned the resulting Threnody from Still. “It was a pleasure to honor [Sibelius],” Arvey recalled on her husband’s behalf, “and to have the little piece played magnificently and later broadcast over the Finnish National Radio.”

In the Threnody, Still channels a bracing tenderness reminiscent of Sibelius. The piece begins with a brass fanfare that leads to a mournful song, interweaving with a snare-drum driven dirge. If the main theme is suggestive of a Black spiritual, it’s not a failure of Still’s “universal” style.

He never meant to banish such influences, but rather to separate them from their historic associations and apply them in unexpected cross-cultural ways, such as in mourning a Finnish colleague.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2024

| First performance | March 14, 1965, the University of Miami Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fabien Sevitzky |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 3 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 6 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 2

Sergei Prokofiev

Born 1891, Sontsivka, Ukraine

Died 1953, Moscow, Russia

During the early years of the last century, Russian society was riven by contradictory forces. Its ruling aristocracy maintained a tenuous grip on power, though revolutionary currents had been in the air for decades. The conservative tendencies of the middle class were opposed by idealistic artists eager to explore new ideas and modes of expression. And the traditions embodied in Russian song and folklore conflicted with the urge many intellectuals felt to assimilate what they considered to be the more advanced outlook of the West.

Something of these tensions inform Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2. The composer was 22 and still a student at the Conservatory in Czarist Russia’s capital of St. Petersburg when he wrote this piece, in the spring of 1913. It proved to be the composer’s most ambitious work to date and remains one of his most challenging concertos to play.

Prokofiev’s fondness for dissonant harmonies and irregular rhythms had already upset some of his professors at the Conservatory, and the Second Piano Concerto did nothing to quiet their apprehensions. Indeed, the work provoked a small scandal at its first performance, in September 1913, before a fashionable audience in an 18th-century palace. Prokofiev, an excellent pianist, played the solo part, having mastered it with much effort—“[it] has turned out to be incredibly difficult and mercilessly tiring,” he wrote of his own music—and his autobiography reports with some pride the walk-outs and derisive comments from some of his more conservative listeners (“the cats on the roof make better music!”).

The concerto that shocked its first listeners, however, is not the concerto performed today. In 1918, while Prokofiev was on tour in the United States, the score was lost in a fire. (The stories vary—a tenant in his St. Petersburg flat may have used it as cooking fuel.) And so Prokofiev reconstructed the work, preserving all the thematic material but creating something “less foursquare” and “slightly more complex” in its fabric. He premiered this version in Paris in 1924 to a much more receptive audience.

The first movement alternates between relatively relaxed and more energetic music, the first (Andantino) coming at the start and close. As in Prokofiev’s first violin concerto, the soloist is given the instruction narrante (in the manner of a narration)—entrusting them with the role of “storyteller” in this music. Prokofiev adopts a more vigorous mode of expression in the main central portion of the movement (Allegro), which culminates in an extended and demanding cadenza for the soloist. The two central movements are shorter and more straightforward. An unbroken stream of fast notes in the piano and shrill orchestral comments dominate the second movement (a lively Scherzo)—this is what Prokofiev described as his “perpetual motion” style. The Intermezzo feigns a rough, barbaric swagger— an example of classic Prokofiev “grotesquerie.” The finale (a “tempestuous” Allegro) unfolds in something of a circular design, bringing together ideas from the previous movements and concluding with the vigorous material heard at the outset.

Adapted from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2009 with additional material by Yvonne Frindle

| First performance | September 5, 1913, at the Russian resort of Pavlovksk, with the composer as soloist and Alexander Aslanov conducting; Prokofiev premiered the reconstructed version in Paris on May 8, 1924, with Serge Koussevitzky conducting |

| First SLSO performance | October 24, 1959, with Malcolm Frager as soloist and Edouard van Remoortel conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | Feb 16, 2019, with Yefim Bronfman as soloist and Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 31 minutes |

Symphony No. 5

Jean Sibelius

Born 1865, Hämeenlinna, Finland

Died 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

Jean Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony began with a deadline nightmare. The Finnish government commissioned it in honor of the composer’s 50th birthday, December 8, 1915, which had been declared a national holiday, and Sibelius was expected to conduct its premiere on that date. Meanwhile, he was deeply in debt and unable to work on the project full time. Because of World War I, he could no longer travel abroad to conduct, collect royalty checks, and do business with his German publisher. As his debts increased, he resorted to writing for local publishers, who were reluctant to buy anything that seemed unlikely to turn a profit.

Sibelius was feeling particularly dismal on August 15, 1914, when he wrote in his diary, “Now I shall be 50. How miserable it is that I must compose miniatures.” With his golden deadline looming, he was desperate to crank out the Fifth, but he kept getting stuck. A month later, in a letter to his close friend Axel Carpelan, he wrote, “God opens his door, and His orchestra plays the Fifth Symphony.” Unfortunately, God kept slamming the door.

When he wasn’t working, Sibelius went for long walks in the woods. He was particularly moved by a sighting of 16 swans in flight, which he described in his diary as “one of the greatest experiences in my life.” It inspired what Carpelan called “the incomparable swan hymn” voiced by the horns in the Fifth’s ecstatic finale.

Somehow Sibelius managed to finish the symphony in time for his big birthday gala, and it was met with overwhelming acclaim—the audience reportedly shrieked with joy—but he remained unsatisfied. For the next four years, while he worked on the Sixth and Seventh symphonies and other projects, he returned obsessively to his Fifth, deleting sections, combining movements, and radically re-imagining the score. In 1916 there was a second premiere for this revised version, but he still could not leave it alone. Despite numerous health crises, the death of Carpelan, and chronic financial trouble, he kept worrying away at the Fifth. In 1917, his beloved homeland gained its independence and he barely mentioned it in

his diary, but lengthy discussions of the Fifth abound. At long last, on November 24, 1919, the definitive version received its first performance. Kaarlo Ståhlberg, Finland’s first president, was among those who attended the first of three sold-out concerts. Almost four years after its premiere, Sibelius finally thought his Fifth was good enough.

Musicologists have quarreled for decades about this symphony—its structure, whether its first movement meets the criteria for sonata form, where various sections begin and end—but none of those details matter once the Fifth has the listener in its mighty grip. From its radiant opening horn call to its weird and stunning conclusion—six staggered chords punctuated by silence—the Fifth showcases nearly every stylistic characteristic that makes Sibelius so Sibelian. The strings buzz and thrum and swarm. The woodwinds burble and sing. The timpani portend. The brass radiates, hovers, takes flight. The changes in meter and tempo, both wrenching and subtle; the persistent variations and deconstructions of its central theme; the way the whole thing keeps breaking apart and reassembling itself: The Fifth tells its own story. It is a story of starting over

and over again until somehow, despite yourself, you find the end.

René Spencer Saller © 2013

Navigating the symphony

Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony follows a symmetrical structure of three movements—a departure from the four-movement Classical symphony of composers such as Beethoven. The first movement—which opens with an important horn call—links what was originally two movements: a slow introduction and a waltz-like “scherzo.” The calm second movement is a set of variations on a rhythmic motif. The third movement reverses the tempo directions of the first by beginning fast and ending slowly. It also introduces one of Sibelius’s most memorable ideas, a noble, “swinging” theme in the horns.

| First performance | December 8, 1915, the composer conducting the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra; the final version was first heard on November 24, 1919, again in Helsinki with Sibelius conducting |

| First SLSO performance | January 25, 1935, Vladimir Golschmann conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | Feb 2, 2013, Hannu Lintu conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, string |

| Approximate duration | 30 minutes |

Artists

Jonathon Heyward

Jonathon Heyward is Music Director of both the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and the Festival Orchestra of Lincoln Center, and he recently completed a four-year tenure as Chief Conductor of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie. He returns to the SLSO following his St. Louis debut in the 2022/23 season.

Guest conducting highlights include debuts and re-invitations with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the London and BBC symphony orchestras, BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Royal Scottish National

Orchestra, and Scottish Chamber Orchestra. In Europe, he performs with NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester, Tonhalle Düsseldorf, Danish National Symphony, Castilla y León Symphony, Galicia Symphony, Brussels Philharmonic, Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine, and MDR-Leipzig Symphony Orchestra. In high demand in his native USA, he also conducts the New York Philharmonic, the Atlanta, Detroit, Houston, Seattle, and Dallas symphony orchestras, and the Minnesota Orchestra.

Equally at home in opera, he made his Royal Opera House, Covent Garden debut conducting Hannah Kendall’s Knife of Dawn. Other music theater highlights include Kurt Weill’s Lost in the Stars (Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra) and the world premiere of Giorgio Battistelli’s Wake (Birmingham Opera Company).

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Jonathon Heyward began his musical training as a cellist. He studied conducting at the Boston Conservatory of Music and London’s Royal Academy of Music, where his teacher was Sian Edwards. Before leaving the RAM, he was appointed assistant conductor

of the Hallé Orchestra, where he was mentored by Mark Elder, and became Music Director of the Hallé Youth Orchestra. In 2023, he was named a

Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music.”

Yeol Eum Son

Yeol Eum Son was born in South Korea and studied piano from a very early age. She was a prizewinner in the 1997 International Tchaikovsky Competition for Young Musicians and won the Oberlin International Piano Competition two years later, at the age of 13. After studies in Korea and Hannover, Germany, she came to widespread attention as a prizewinner in the 2009 Van Cliburn Competition and Silver Medalist in the 2011 International Tchaikovsky Competition. Since then she has achieved acclaim in a wide-ranging repertoire from Bach to contemporary works, and in particular for her Mozart concerto interpretations.

In addition to the SLSO, this season she makes concerto debuts with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, Düsseldorf Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Tonkünstler Orchestra (in Vienna and London), National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Galicia Symphony Orchestra, Naples Philharmonic, the Colorado and Baltimore symphony orchestras, and Los Angeles Philharmonic. In 2024/25 she also returns to the National Arts Centre Orchestra in Ottawa, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, and Orquestra Sinfónica do Porto.

Collaborations of previous seasons include the Konzerthaus Orchestra Berlin, Castilla y León, Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, and Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra. In North America she has appeared with the Detroit and San Diego symphony orchestras, and in Australasia with the Sydney, Melbourne, West Australian, and Tasmanian symphony orchestras, and the Auckland Philharmonia.

She is also in demand as a recitalist, and recent highlights include debut appearances at the Edinburgh International, Rosendal and Risør Chamber Music, and Singapore International Piano festivals, as well as return visits to the Helsingborg Piano Festival and the Melbourne Recital Centre.

In addition to her busy performance diary, she has an active recording

schedule with Naïve Records.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.