Slatkin and Ax (October 11-12, 2025)

Program

October 11-12, 2025

- Leonard Slatkin, conductor

- Emanuel Ax, piano

Leonard Slatkin (b. 1944)

Schubertiade: An Orchestral Fantasy

US Premiere

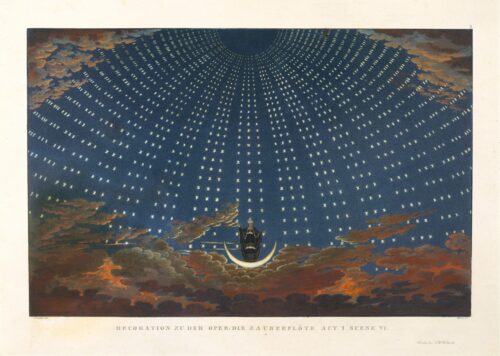

W.A. Mozart (1756-1791)

- Piano Concerto No. 25 in C major, K. 50

- Allegro maestoso

- Andante

- Allegretto

Emanuel Ax, piano

Cadenza by Alfred Brendel

Intermission

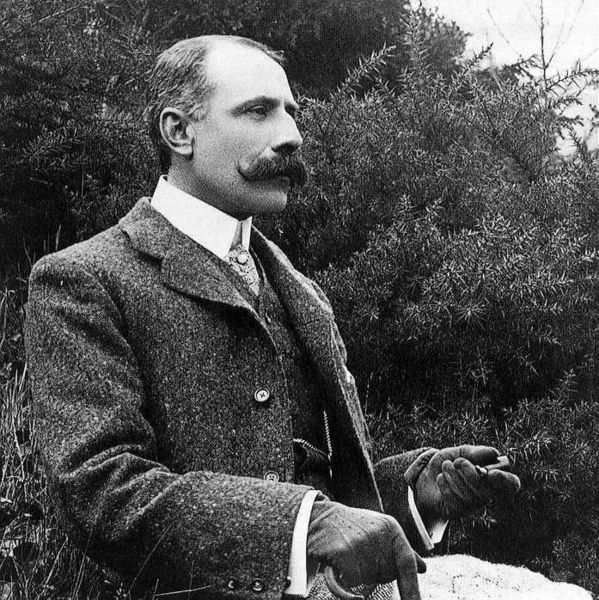

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

- Symphony No. 1 in A flat major, Op. 55

- Andante (Nobilmente e semplice) – Allegro

- Allegro molto –

- Adagio

- Lento – Allegro

Schubertiade: An Orchestral Fantasy

Leonard Slatkin

Born 1944, Los Angeles, California

The composer writes:

In April 2022, when we were all starting to come out of hiding from the global pandemic, I had the privilege of conducting the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra in a concert honoring the 50th anniversary of their becoming a professional orchestra. When we had concluded Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, I sat, somewhat exhausted, in the dressing room.

Several administrators of the orchestra came to greet me and during the course of our chat, they asked my wife, composer Cindy McTee, if she would be interested in writing a work that would commemorate the 200th year of the death of Franz Schubert. She was flattered but declined. I, however, became quite intrigued by the idea and suggested the piece be written by me. Since I was scheduled to return to the orchestra in 2025, and it was desired to have this composition performed in advance of the actual anniversary (2028), the timing seemed appropriate.

Almost immediately, ideas started swirling around in my head. Should it be a totally original composition, with no musical reference to the Austrian master? Or might it be a hybrid, where various strains of Schubert fragments are heard alongside new material? I decided on the latter and used the composer’s “Unfinished” Symphony (No. 8 in B minor) as a starting point.

Schubert himself was rather poor for most of his brief life. In order to get his music heard, he would organize soirees in private homes, where friends would gather to play and sing his music. The composer was usually at the piano, and these events became known as Schubertiades. When I began to write this piece, I imagined this tradition extended into our own time.

Schubertiade is in three parts, with descriptive moments placed before each. The first begins with Schubert, not seen, at the piano playing the opening of his monumental B flat major sonata. This is rudely interrupted by the orchestra, representing the guests, who arrive rather vociferously with a series of fanfares and flourishes in the trumpets, horns, and flutes.

The initial section is taken from the first six bars of the “Unfinished” Symphony and is cast as a passacaglia. This is a set of variations over the bass line which opens the symphony. Other elements of the first movement are introduced but these become more and more distorted as the guests indulge in some Glühwein, a kind of mulled wine.

Schubert is playing one of his impromptus when several more friends arrive, and they are introduced by the same instruments who greeted the earlier visitors. When they settle down, more recent composers— perhaps Philip Glass or Steve Reich—proceed to take Schubert’s main themes from the slow movement of the symphony and alter them in a mash-up of harmonic and rhythmic glee. This becomes the second part of Schubertiade.

It is raining as the guests depart into the evening. A final reference to the fanfares is heard—this time played in reverse. The composer is left at his piano, trying to complete the sonata melody that began the evening, and which, at least in this version, will remain “unfinished.”

Leonard Slatkin © 2025

| First performance | January 31, 2025, the composer conducting the Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 4 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, 2 harps, celeste, off-stage piano, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 15 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 25

in C major, k. 503

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born 1756, Salzburg, Austria

Died 1791, Vienna, Austria

During the course of his career, Mozart composed some two dozen concertos for piano and orchestra. Fourteen of them date from a period of just over three years, beginning in the winter of 1782–83, and they constitute the most ambitious and outwardly brilliant works of the composer’s maturity. They embody a wide range of expression, from bright optimism and lyric intimacy on one hand to stormy drama and stern tragedy on the other. From a compositional standpoint, the series shows a more or less progressive expansion of form and deepening of content. The musical architecture becomes more imposing in scale, contrapuntal textures increasingly enrich the discourse, and the orchestra, particularly the woodwind section, takes on an ever more important and expressive role.

These works represent the Classical-period concerto in its most elaborate and most perfect realization. But their author did not create them in a self-conscious attempt to develop the genre. Rather, he cultivated the keyboard concerto for quite pragmatic reasons. Early in 1783, Mozart had launched his own series of subscription concerts or “academies”—presentations that soon became a major attraction within the music-loving circles of Vienna’s upper class and one of the composer’s chief sources of income. Their programs consisted entirely of Mozart’s own compositions—orchestral pieces, chamber music, and vocal works—as well as improvisations at the piano, and the principal work was always a keyboard concerto. Mozart’s recognition as a composer was equaled, if not exceeded, by his reputation as a virtuoso pianist, and his concertos, in which he invariably performed the solo part, allowed him to display both facets of his musicianship.

Following the summer of 1786, Mozart apparently hoped to launch another series of academies. He planned to begin with a concert in December of that year, and for this he produced the Piano Concerto in C major, K. 503. But his period of public favor in the Austrian capital had come to an end. Why this occurred remains uncertain. Whatever the cause, Mozart’s public performances now declined sharply in number. His concert in December 1786 seems not to have taken place, and the first performance of this concerto was delayed until the following year. Mozart composed only two more piano concertos during his remaining five years.

The present work, therefore, crowns the period of Mozart’s devotion to piano concerto composition. More fitting music for this purpose would be difficult to imagine. This is as majestic a composition as Mozart ever wrote. It unfolds along spacious lines. (The opening movement is the longest in any of his piano concertos.) Its sonorities are rich and brilliant, due in no small part to the inclusion of trumpets and timpani in the orchestra, and its musical discourse conveys an unhurried grandeur that the pianist and writer Charles Rosen has described aptly as “tranquil power.”

Mozart establishes the character of the work in its opening measures of the Allegro maestoso, where the broad chords introducing the first theme create a sense of splendor and ceremony. He varies his harmonies with frequent shifts between the major and minor modes, and he extends that shifting harmonic coloration to his second subject, a march-like tune presented by the strings in C minor and echoed immediately in C major by the woodwinds. If this melody seems to grow naturally, even inevitably, out of the preceding music, it surely is because the rhythmic figure of its first four notes has appeared throughout the previous passage. That rhythm, three short notes followed by a longer one, was a favorite of Beethoven’s—it figures prominently in his Fifth Symphony, Egmont Overture, and Piano Concerto No. 4, for example—and Mozart uses it throughout the first movement of the present concerto with an insistence more characteristic of his younger colleague than of his own usual practice. The piano introduces several new thematic ideas during its exposition, but the movement’s development section concerns itself entirely with the little march tune, which sounds at last in four-part echo with itself.

The ensuing Andante, though far more contemplative than the opening movement, also begins with a descending major chord and shares the sense of breadth that has characterized the initial portion of the work. The finale (Allegretto), despite the almost child-like quality of its recurring principal theme, contains some of the most brilliant passages in any of Mozart’s concertos.

Abridged from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2007

| First performance | March 7, 1787, with Mozart as soloist, directing from the keyboard |

| First SLSO performance | February 14, 1973, with Charles Rosen as soloist and Jerzy Semkow conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 24, 2012, with soloist Martin Helmchen and Jaap van Zweden conducting |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 30 minutes |

Symphony No. 1

Edward Elgar

Born 1857, Worcester, England

Died 1934, Worcester

Edward Elgar was past the age of 50 and at the height of his powers when he at last produced the symphony for which his friends and admirers had long been hoping. The creative mastery that the composer now commanded had not come easily. From late adolescence, Elgar worked as a musical journeyman, teaching violin and piano, playing in local orchestras, occasionally conducting, and writing pieces for musicians in his area whenever he could. As a composer he was almost entirely self-taught, and his early musical essays were hardly distinguished. But Elgar persevered, developing assurance and skill through that most honest of methods: trial and error.

In 1898, Elgar began writing a symphony. Whether because he really felt that there was no financial justification for the endeavor or because he was not yet sufficiently confident in his handling of large-scale orchestral composition, he soon abandoned this project. But the following year, his Enigma Variations was performed to great acclaim in London. The success of this piece must have removed much of Elgar’s doubt as to his readiness for symphonic composition. The subsequent completion of several oratorios and some smaller orchestral pieces provided further preparation. Finally, Elgar began sketching a new symphony in the summer of 1907, completing it in September 1908.

The first performance, which took place in December of the same year, in Manchester, was perhaps Elgar’s greatest public triumph. The audience burst into applause after the Adagio and again at the close of the work, calling the composer repeatedly to the stage to receive their accolades. Hans Richter, the celebrated conductor who directed the performance, pronounced the piece “the greatest symphony of modern times, and not only in this country.”

Listeners who associate Elgar only with the straightforward, relatively simple music of his popular Pomp and Circumstance marches, or even the genial musical portraits of friends and family presented in the Enigma Variations, may be surprised at the thoughtful construction and complex sentiments of this symphony.

Despite its considerable length, this is a tightly knit work, thanks to thematic links between the first and final movements and between the two inner movements. The most important subject appears immediately following the anticipatory drum roll of the opening measures. This melody, at once march-like and hymn-like, dominates the slow introduction (Andante) of the first movement and serves as a motto theme for the entire symphony. Its character, aptly described by Elgar’s expression marking as “noble and simple,” is sharply contradicted by the impassioned Allegro into which it leads. Here the mood is one of agitation, despite the appearance of several lyrical subsidiary melodies. Contrast is provided mainly in two brief references to the opening motto theme during the development section, and by the triumphant return of that idea during the closing coda section.

The second movement (Allegro molto) begins as a nervous, scurrying scherzo, proceeds to a slightly sinister march passage, and arrives at a pastoral episode scored for violins, harp, and flute. These varied ideas are then juxtaposed and combined, leading without pause to the Adagio.

The smooth transition is no accident, for this third movement is really an extension and transformation of the second. The theme announced by the strings in the opening measures is composed of the very same notes as the running passage heard at the start of the scherzo, though its more relaxed tempo and rhythm render it almost unrecognizable as such. Deeply poignant and tender, this music is the heart of the symphony, and more than one commentator has compared its religious serenity to the great adagios of Beethoven.

The finale returns to the restless drama, and to some of the thematic material, of the symphony’s opening. Both the angular melody heard as a bass clarinet solo at the beginning of the introductory Lento section and the motto theme, which soon appears in the strings, are recollections of the initial movement. As in the opening portion of the symphony, the slow introduction gives way to an intense Allegro. The music drives forcefully to its climax, at which point the motto theme once again appears, emerging majestically in the winds while string figures swirl ecstatically around it.

Paul Schiavo © 2009

| First performance | These concerts |

| First SLSO performance | February 20, 1975, Alexander Gibson conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 5, 2019, Edo de Waart conducting |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, 2 harps, strings |

| Approximate duration | 50 minutes |

Artists

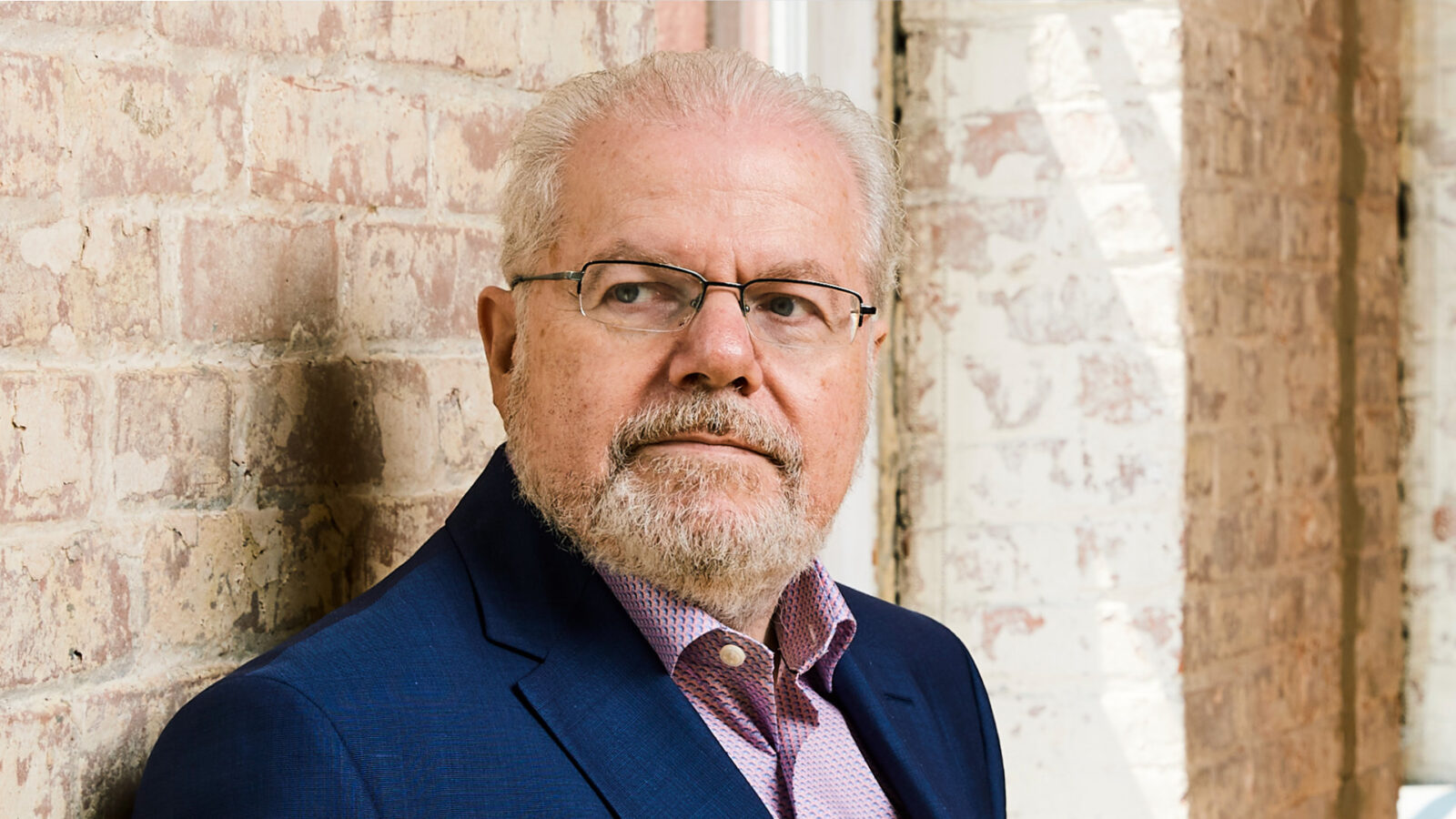

Leonard Slatkin

In addition to his role as Conductor Laureate of the SLSO, Leonard Slatkin is Music Director Laureate of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Directeur Musical Honoraire of the Orchestre National de Lyon, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquesta Filarmónica de Gran Canaria, Artistic Consultant to the Las Vegas Philharmonic, and Artistic Advisor to the Nashville Symphony. He has conducted virtually all the leading orchestras in the world and has also served as principal guest in Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and Cleveland. He maintains a rigorous schedule of guest conducting throughout the world, and is active as a composer, author, and educator.

The 2025/26 season also includes guest engagements with the National Symphony Orchestra (Ireland), Manhattan School of Music Symphony Orchestra, USC Thornton Symphony, Las Vegas Philharmonic, Taiwan Philharmonic, KBS Symphony Orchestra (Seoul), Gunma Symphony Orchestra, NHK Symphony Orchestra (Tokyo), Nashville Symphony, Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, Warsaw Philharmonic, Franz Schubert Filharmonia (Barcelona), Prague Symphony Orchestra, Filarmonica George Enescu (Bucharest), and the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra.

His discography has earned six Grammy awards and 35 nominations. Naxos recently reissued Vox audiophile editions of his SLSO recordings featuring music by Gershwin, Rachmaninoff, and Prokofiev. Other recent releases include Slatkin Conducts Slatkin—featuring pieces written by generations of his family—as well as music by Saint-Saëns, Ravel, Berlioz, Copland, Borzova, McTee, and John Williams.

A recipient of the prestigious National Medal of Arts, he also holds the rank of Chevalier in the French Legion of Honor. He has received the Prix Charbonnier from the Federation of Alliances Françaises, Austria’s Decoration of Honor in Silver, the League of American Orchestras Gold Baton Award, and the 2013 ASCAP Deems Taylor Special Recognition Award for his book, Conducting Business, which was followed by Leading Tones (2017) and Classical Crossroads (2021).

Emanuel Ax

Born to Polish parents in what is today Lviv, Ukraine, Emanuel Ax moved to Canada with his family when he was a boy. He made his New York debut in the Young Concert Artists Series, and in 1974 won the first Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Competition in Tel Aviv. In 1975 he won the Michaels Award of Young Concert Artists, followed four years later by the Avery Fisher Prize.

Highlights of the 2025/26 season include concerts with the Philadelphia Orchestra in Carnegie Hall, and an Asian tour to Tokyo, Seoul, and Hong Kong. He recently gave the premiere at Tanglewood of a concerto written for him by John Williams, and in 2026 will perform it in subscription concerts with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and New York Philharmonic. In addition to the SLSO, he returns as a guest artist to orchestras in Dallas, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Charleston, Madison, Naples, and New Jersey. In recital he can be heard in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Santa Barbara, Des Moines, Cedar Falls, Schenectady, and Princeton. An extensive European tour will include concerts in Munich, Prague, Berlin, Rome, and Torino.

Emanuel Ax has been a Sony Classical exclusive recording artist since 1987, and following the success of a Brahms trios album with Leonidas Kavakos and Yo-Yo Ma, the trio launched an ambitious project to record all the Beethoven trios and symphonies arranged for trio, of which the first three discs have been released. He has received Grammy Awards for the second and third volumes of his cycle of Haydn piano sonatas. He has also made a series of Grammy-winning recordings with Yo-Yo Ma of the Beethoven and Brahms sonatas for cello and piano. In 2004, he contributed to an International Emmy Award-winning BBC documentary commemorating the Holocaust that aired on the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. In 2013, his recording Variations received the Echo Klassik Award for Solo Recording of the Year (19th Century Music/Piano).

Mr. Ax is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and holds honorary doctorates of music from Skidmore College, New England Conservatory of Music, Yale University, and Columbia University.