Slatkin’s Legacy (October 25 & 27, 2024)

Program

October 25 & 27, 2024

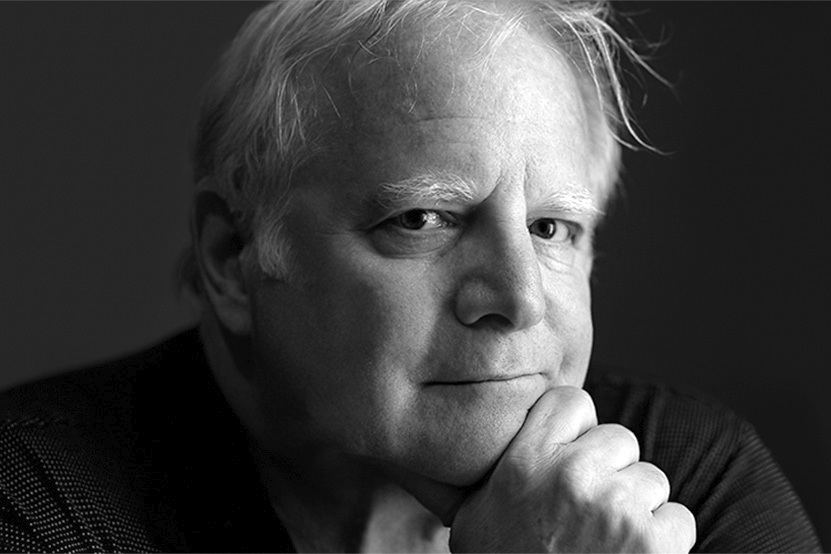

Leonard Slatkin conductor

Cindy McTee (b. 1953)

- Timepiece for orchestra

Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757) arranged by

Leonard Slatkin (b. 1944)

- Five Sonatas for orchestral wind ensemble

- Sonata in D minor (Gavotta. Allegro), Kk.64

- Sonata in B minor (Andante mosso), Kk.87

- Sonata in C major (Allegro), Kk.133

- Sonata in E major (Andante), Kk.380

- Sonata in D major (Presto), Kk.492

World Premiere

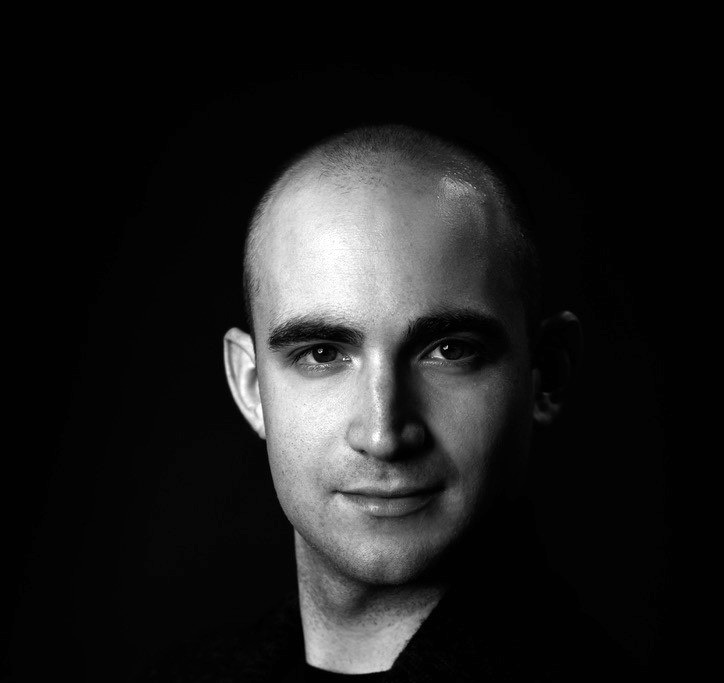

Daniel Slatkin (b. 1994)

- Voyager 130

U.S. Premiere

Intermission

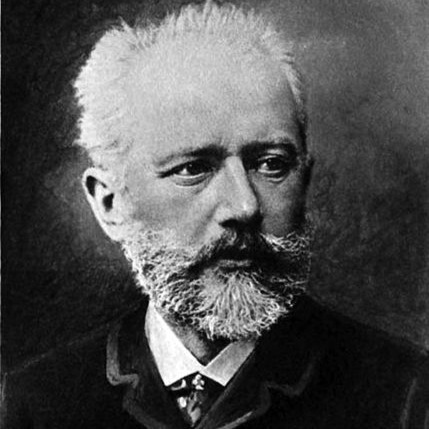

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

- Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

- Andante – Allegro con anima

- Andante cantabile con alcuna licenza

- Valse (Allegro moderato)

- Finale (Andante maestoso – Allegro vivace)

Slatkin’s Legacy:

A Birthday CelebrationA Celebration

Four generations of musical “Slatkins” are associated with the city of St. Louis. For this special program celebrating his 80th birthday, Conductor Laureate Leonard Slatkin has shaped a program around the themes of family, community, and musical legacy. He spoke to Yvonne Frindle about his approach to programming and what to listen for in today’s concert.

The “Slatkin Legacy” begins in 1904 when Chaim Peretz Zlotkin, Leonard Slatkin’s grandfather, arrived in the United States and settled in St. Louis, with a name change courtesy of Ellis Island. Leonard’s father Felix was born in St. Louis. Leonard himself spent 27 years in the city—shaping a rich and memorable association with the SLSO—and his son Daniel was born here. Felix was a violinist as well as a conductor and arranger, his wife Eleanor Aller was a cellist, and together they founded the Hollywood String Quartet, the first major American chamber group. Leonard’s brother Frederick was also a cellist.

“I’m using my 80th anniversary to celebrate my family history as much as possible,” says Leonard, “with the living members representing four generations of Slatkins.” The result is a program of music by Leonard’s wife Cindy McTee, his son Daniel, and Leonard himself. Tchaikovsky is the honorary Slatkin, included as a nod to Leonard’s achievements at the SLSO.

These can be traced back to his time as Assistant Conductor. “The early years,” he explains, “formed the basis of what would become the signatures of my career. We were investing in American music, English music, French music, and Slavic and Russian music because of my heritage.”

He explains that, until the early ̀70s, the major American orchestras had relied a lot on Russian repertoire—“you heard a great deal of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky and Rachmaninoff”—but tastes changed with an influx of music directors such as Georg Solti in Chicago, who was more interested in Austro-Germanic music. “Here in St. Louis, we played a lot of Russian music because other orchestras weren’t doing it anymore, together with American music, which gave this orchestra a specific profile.” But the SLSO also toured regularly to New York, where it had a tremendous following, precisely because its touring programs featured music that “other orchestras couldn’t or wouldn’t do,” including “absolutely outrageous pieces” like William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, an evening-length setting of William Blake’s poetry that calls for 500 or so performers. “We got this reputation for being just a little bit off-center.”

A Great Opener

Leonard and Cindy married in 2011, but he’d begun conducting her music in the early 1990s. They’d first met, he recalls, at a reading of new works organized by composer Joan Tower, and he commissioned works from Cindy when he was music director in Detroit and Washington, D.C. Audiences in St. Louis already know Cindy McTee very well, and as it turns out, Timepiece is the only orchestral work of hers that the SLSO hasn’t programmed before. “It’s a great opener,” says Leonard, “because it has an immediacy to it, a rhythmic drive. There are jazz inflections and the orchestration is very colorful.”

Timepiece is organized in two sections: it begins slowly, as if “holding” time. Once the clock-like pulse emerges, the driving energy of the music takes over. You can listen for the rhythmic vitality and for the orchestral colors, says Leonard, “you don’t even have to know anything about the piece. But you know from the title there’s going to be a clock in there, and it’s going to be a woodblock. The music is energetic and virtuosic with lots of ideas flying around, but it’s listenable because Cindy does the one thing so many composers today don’t do: she takes you back to the materials she presented at the beginning—like an essay.”

Transforming Scarlatti

With the five Scarlatti sonatas, we get to see Leonard Slatkin, composer. The conductor’s role is normally “recreative” says Leonard, “the composer’s work is already there, and I just have to ask what he or she had in mind. It’s nice

to be in touch with the creative side.”

Just as he wanted to program something of Cindy’s that he’d not conducted in St. Louis before, so Leonard looked for something fresh among his own compositions, turning to a pandemic project. “I didn’t mind the pandemic so much, because I got a lot done. I finished books, wrote music, and became a pretty good cook.” One of the compositions was today’s arrangements of Scarlatti keyboard sonatas.

As a young pianist, Leonard loved Scarlatti. “A lot of the sonatas you can sight read, many of them you can’t. But it was just heaven to play them. The real turning point for me came in 1964 when harpsichordist Fernando Valenti played an all-Scarlatti program in Aspen. I wasn’t keen on the harpsichord back then, but all of a sudden I heard the possibilities. So when I came to St. Louis, I invited him to collaborate in a Sunday Festival of Music concert: we did a second half where he would play a Scarlatti sonata on the harpsichord, then I would play another on the piano, and then we’d play an orchestral version—three different idioms.”

The main challenge for an arranger is the intrinsically keyboard character of the sonatas. They were composed for the harpsichord, often using techniques such as hand-crossing, and “the majority of them don’t suit any other instrument.” That meant searching through all 555 sonatas to find five that would work for orchestra and showcase Scarlatti’s inventiveness. “I especially wanted to find the ones with a Spanish flavor and unusual harmonies.”

Surprisingly for a symphonic program, the suite features an orchestral wind ensemble—no strings, no percussion, no saxophones. The St. Louis winds are pretty good, says Leonard admiringly, and it will be a different sonority to hear them without the strings.

In its keyboard form, Scarlatti’s Sonata in D minor (Gavotta) is notable for its “wrong-note” chords that clang in the left hand. These are given to the brass, while blocks of woodwind color dance above. On the keyboard, the two hands of the Sonata in B minor entwine; in Leonard’s version, these weaving, mournful lines are initially shared by English horn and clarinet. The Sonata in C major restores the rhythmic energy and takes us into remoter harmonic realms. In the elegant Sonata in E major the distinctive, trilling ornaments on repeated notes are assigned to the flutes. With the Sonata in D major, the suite concludes with a kind of fandango, in which fragments of melody are tossed between the different instruments while bassoons and low clarinets imitate the strumming of a guitar.

Music for a space odyssey

Given his family heritage, it was inevitable Daniel would end up working in music, and at the University of Southern California he studied the business side of the industry. Then, says Leonard, “out of nowhere he decided he wanted to compose. I don’t really know where this came from, and I don’t think he does either. But he took an 18-month course in film scoring and it was astonishing how fast he picked it up, and how quickly he found a compositional voice.” The second surprise was Daniel’s debut as a symphonic composer during Leonard’s final year as music director in Detroit.

At a concert in honor of Leonard’s tenure with the DSO, Daniel appeared on stage to conduct a piece he’d written for the occasion. “I don’t remember much about it, I was too busy crying,” recalls Leonard, “but when I finally looked at the music, I thought, ‘He’s really got a gift for this.’”

The third surprise was when Leonard invited Daniel to compose something for his 80th birthday: “It turns out he’d already started on his own.”

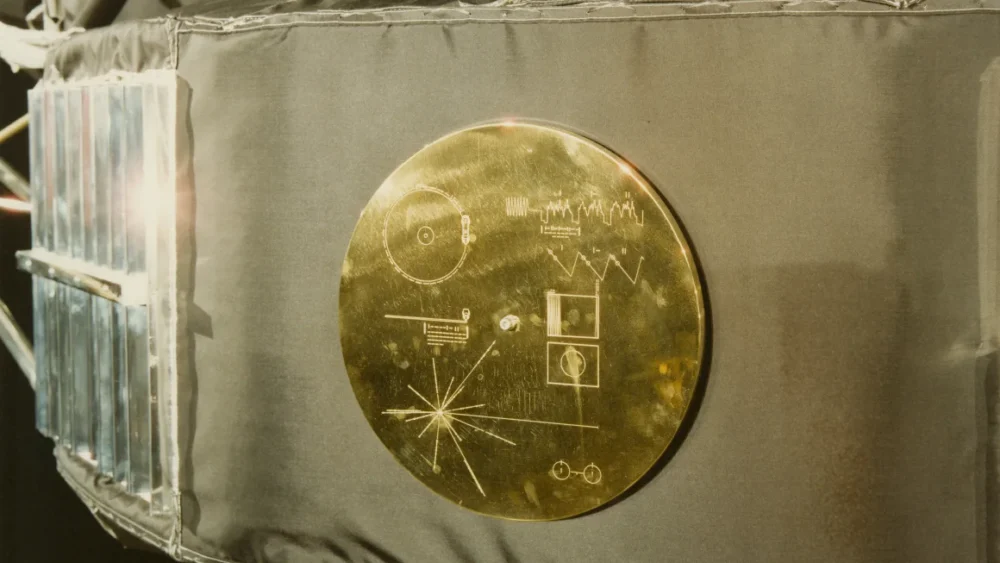

The inspiration for Voyager 130 was the Cavatina movement from Beethoven’s Op. 130 string quartet, which was sent into space on the Voyager Golden Record, and Leonard observes that “one of the fascinating things for composers who are used to working in the visual medium is how, when they don’t have it, they can create their own imagery.”

Voyager 130 begins on the launchpad, with computer blips, mechanical sounds, and the rumbling of low instruments. A single oboe represents the Voyager communications system and the English horn introduces an original motif. As momentum builds and the rocket launches, a fragment of Beethoven’s Cavatina is heard like a fanfare (horns and violas). About four minutes in, as if marveling at the beauty of Earth from outer space, we hear the first page of the Cavatina, played in its original form by a string quartet. But wait, do you hear voices? These are the spoken greetings from the Golden Record. As the orchestra re-enters, the Cavatina and Daniel’s original motif are combined in new arrangements, each one grander than the next, as the probe passes Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune… Reaching the edge of the solar system, Voyager enters a void. Distorted sounds from the Golden Record, icy, shivering strings, and a somber duet between French and English horns combine to evoke what Daniel describes as “the dizzying feeling of being confronted by this enormity.” The music then builds to a triumphant climax, from which emerges the original string quartet, weaving together new fragments of the Cavatina. Then everything fades as Voyager continues on its journey into the beyond.

The Golden Record in its cover, attached to Voyager 1, summer of 1977.

At home with Tchaikovsky

Tchaikovsky has been a welcome presence on concert programs for nearly as long as the SLSO has been in existence. But for a long time, critics and scholars were dismissive. There’s a reason for this, explains Leonard, citing the perspective he gained from a “deep dive” he once programmed in Detroit—all the Tchaikovsky symphonies and concertos in three weeks. “Part of the problem for some people is that the first three symphonies are rooted in Slavic tradition,” he says. “They’re not particularly symphonic—not like Schumann, not like Brahms—they’re just Russian music given the name ‘symphony.’ But with the Fourth Symphony, Tchaikovsky wants to be taken more seriously and he moves towards the European model of what a symphony is. In the Fourth, he brings his first-movement tunes back in the finale, and in the Fifth he adopts a cyclic structure, so the tune now permeates all four movements. But he was already so ingrained as a stereotypical Russian composer that it was difficult for the musical establishment to take him seriously—they would always hear the more folksong-oriented elements, and the melodic qualities that made him such a great ballet and opera composer.”

The advocacy of conductors such as Leonard Slatkin has made a difference to Tchaikovsky’s reputation over the past 60 years or so, although he laments that certain pieces still aren’t programmed often enough in concerts: Manfred, for example, as well as Hamlet and The Tempest.

On the surface, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth is a conventional symphony. It’s in four movements: the first beginning with a slow introduction, the fourth providing a rousing finale; between them an impassioned slow movement and a dance movement (a waltz). But lurking in the background is the kernel of a “program” or narrative that he jotted down for the first movement. The Introduction, he wrote, represents “Complete resignation before Fate, or, which is the same, before the inscrutable predestination of Providence.” The main portion of the movement has two themes: “(I) Murmurs, doubts, plaints, reproaches against XXX” and “(II) Shall I throw myself into the embraces of Faith???” In the corner of the page: “A wonderful program, if I could only carry it out.” Key to the whole symphony is a Fate motto, which is introduced by two clarinets at the very beginning, and functions like the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth. As a unifying gesture, the Fate motto twice interrupts the second movement, and it steals in at the end of the third movement before reappearing at the beginning of the finale.

Reflecting on Tchaikovsky’s Fifth, Leonard observes that he probably conducts it faster now than when he was younger, especially the first movement. “I feel more of a sense of urgency, a kind of ‘Sturm und Drang’ [storm and stress] going on, and certainly more flexibility.” Similarly, in the waltz movement he strives for elegance, while keeping that momentum. Leonard seeks to accentuate the marvelous dramatic contrasts in the symphony. In the second movement, for example, Tchaikovsky “has two intrusions of martial music that break up these very long stretches of beautiful poetry—the horn, the oboe, cellos.” And he emphasizes the sense of intensity and thematic unity in the symphony—“structure and architecture in music have become much more important to me now.”

Yvonne Frindle © 2024

Listening Guides are adapted in part from notes by Cindy McTee and Daniel Slatkin.

Keynotes

Timepiece

Cindy McTee

Born 1953, Tacoma, Washington

Cindy McTee grew up in a musical family and studied piano with a teacher who encouraged improvisation. She majored in composition at Pacific Lutheran University where she met Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki. Other influences have included Jacob Druckman, with whom she studied at Yale. For 30 years she pursued a teaching career alongside composing, retiring from academia in 2011. That same year, she married Leonard Slatkin. Her music has been praised for its invention, craft, and respect for tradition, as well as its “charging, churning celebration of the musical and cultural energy of modern-day America.”

Timepiece for orchestra

Musical time shapes this work. It begins slowly, “before” time, then a clock-like pulse emerges to provide the driving force behind the remaining six minutes. At the time she was composing Timepiece, McTee was reading Carl G. Jung and thinking about the tensions between oppositions—thought and feeling, mind and body, conscious and unconscious—and in the music she aimed to integrate and reconcile opposing elements. For example, circular patterns (ostinatos) allowed her to both suspend time and create a sensation of continuous forward movement. “Discipline yields to improvisation,” she writes, and “humor takes its place comfortably alongside the grave and earnest.”

| First performance | February 17, 2000, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andrew Litton |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 8 minutes |

Five Sonatas

Domenico Scarlatti

Born 1685, Naples, Italy

Died 1757, Madrid, Spain

Born in the same year as J.S. Bach and Antonio Vivaldi, Domenico Scarlatti was an original genius of the Baroque era, best-known for his 555 keyboard sonatas (a memorable number, like Vivaldi’s 600 concertos). Italian born, he moved to Lisbon when he was in his late 30s and in 1729 settled in Madrid, spending the rest of his working life in the service of María Bárbara, Portuguese princess and Spanish queen.

Five Sonatas for orchestral wind ensemble

With the exception of the “Cat’s Fugue” (Kk.30), in which the composer’s cat supposedly picked out the theme by walking on the keyboard, Scarlatti’s sonatas have no nicknames. Unlike later piano sonatas, they are single-movement works, following a two-part structure with each part repeated, and they showcase keyboard effects and virtuoso finger technique while revealing a quirky originality of harmonic style. For this suite, Leonard Slatkin chose five contrasting sonatas that lend themselves to performance by wind instruments while still representing Scarlatti’s signature style, especially the Spanish influence in his music.

| First performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones |

| Approximate duration | 16 minutes |

Voyager 130

Daniel Slatkin

Born 1994, St. Louis, Missouri

Daniel Slatkin is a composer for film, television, and the concert hall. His musical journey began at the piano and he studied the business of music at the University of Southern California, but he didn’t contemplate a career as a composer until after graduation, when he studied film scoring through UCLA Extension. He scored his first feature film at 23, and in 2018 made his orchestral composing (and conducting) debut with In Fields, commissioned by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra in honor of his father’s final year as music director.

Voyager 130

The inspiration for Voyager 130 was the Cavatina movement from Beethoven’s Op. 130 string quartet, which was included on the Golden Record, launched into space on the Voyager probes in 1977. The music evokes their journey through space—the Cavatina providing thematic material, together with an original motif, while audio samples from the Golden Record emerge from the background. Both musical ideas are presented in new arrangements of increasing grandeur until Voyager reaches the edge of our solar system. From the final climax emerges peace, with just four string players, and gradually the sounds fade…

| First performance | September 27, 2024, in Dublin by the National Symphony Orchestra, Ireland, conducted by Leonard Slatkin |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo and alto flute), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, celesta, electronic media, strings |

| Approximate duration | 14 minutes |

Symphony No. 5

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born 1840, Votkinsk, Russia

Died 1893, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Tchaikovsky represented a new direction for Russian music in the late 19th century: fully professional and cosmopolitan in outlook. He embraced the genres and forms of Western European tradition—symphonies, concertos, and overtures—bringing to them an unrivalled gift for melody. But many music lovers would argue that it’s his ballets that count among his masterpieces, and it’s Tchaikovsky’s extraordinary dramatic instinct that comes to the fore in all his music, whether for the theater or the concert hall.

Symphony No.5

Tchaikovsky left this symphony without a narrative scenario or “program,” but his sketches and notes suggest that he’d begun with one in mind. Fate is the theme: doubt, struggle, resignation, faith, and ultimately a kind of triumph. The music traces that emotional trajectory by following a harmonic journey first tried by Beethoven in his own Fifth Symphony: it begins in a minor key and ends in the major key. The thing to listen for and keep in your memory is the very opening of the symphony: a motto theme played by two clarinets. This motto will return: as an interruption to the dreamy second movement, sneaking in at the end of the third movement waltz, and with a complete shift of character to begin the finale.

| First performance | November 17, 1888, in Saint Petersburg, the composer conducting |

| First SLSO performance | February 4, 1909, Max Zach conducting |

| First SLSO performance with Leonard Slatkin | August 14, 1971, at the Mississippi River Festival |

| Most recent SLSO performance with Leonard Slatkin | July 25, 1992, while Director of the Blossom Festival |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 50 minutes |

Artists

Leonard Slatkin

In addition to his role as Conductor Laureate of the SLSO, Leonard Slatkin is Music Director Laureate of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Directeur Musical Honoraire of the Orchestre National de Lyon, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquesta Filarmónica de Gran Canaria. He has conducted virtually all the leading orchestras in the world, and in addition to his music director roles, he has served as principal guest in Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and Cleveland. He maintains a rigorous schedule of guest conducting, and is active as a composer, author, and educator.

To celebrate his 80th birthday, he is returning to orchestras he led as music director, including the DSO, ONL, SLSO, and National Symphony Orchestra (Washington, DC). Other highlights of the 2024/25 season include the New York Philharmonic, Nashville Symphony, North Carolina Symphony, Manhattan School of Music Symphony Orchestra, Eastman Philharmonia, National Symphony Orchestra (Ireland), Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra, Osaka Philharmonic, Hiroshima Symphony Orchestra, Kristiansand Symfoniorkester, Jerusalem Symphony, and Opera Theatre of St. Louis. Two new works—Schubertiade and his arrangement of Scarlatti sonatas—are receiving world premieres this season.

His extensive discography has received six Grammy awards and 35 nominations. Naxos recently reissued Vox audiophile editions of his SLSO recordings featuring music by Gershwin, Rachmaninoff, and Prokofiev. Other recent releases include Slatkin Conducts Slatkin—a compilation of pieces written by generations of his family—as well as music by Ravel, Saint-Saëns, Berlioz, Copland, Borzova, McTee, and John Williams.

A recipient of the prestigious National Medal of Arts, Leonard Slatkin also holds the rank of Chevalier in the French Legion of Honor. He has received the Prix Charbonnier from the Federation of Alliances Françaises, Austria’s Decoration of Honor in Silver, the League of American Orchestras Gold Baton Award, and the 2013 ASCAP Deems Taylor Special Recognition Award for his debut book, Conducting Business, which was followed by Leading Tones (2017) and Classical Crossroads (2021). His latest books are Eight Symphonic Masterworks of the Twentieth Century and Eight Symphonic Masterworks of the Nineteenth Century.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.