Stéphane Conducts Ravel (January 17 & 19, 2025)

Program

January 17 & 19, 2025

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Kirill Gerstein, piano

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

- Ma Mère l’oye (Mother Goose) Suite

- Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant

(Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty)

Petit Poucet

(Tom Thumb)

Laideronnette, Impératrice des Pagodes

(Laideronnette, Empress of the Pagodes)

Les Entretiens de la Belle et de la Bête

(Conversations of Beauty and the Beast)

Le Jardin féerique

(The Enchanted Garden)

- Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant

- Piano Concerto in G major

- Allegramente

- Adagio assai

- Presto

Kirill Gerstein, piano

Intermission

- Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

- Lento – Andante –

- Allegro – Tempo primo

Kirill Gerstein, piano

- Boléro

Sonic Impressionism

The music of Maurice Ravel is all about the sound—the miraculous colors and effects possible when eighty or so musicians assemble to perform music by a virtuoso of the orchestra. Whether you’re a performer or a listener, the experience of Ravel’s “sonic impressionism” is exhilarating, especially in the hands of a conductor with an affinity for French music.

This program is even more exciting for the presence of not one but two piano concertos. Ravel himself was an accomplished pianist—not a virtuoso like Sergei Rachmaninoff but good enough to contemplate performing his own piano concerto. But more important, he had an astonishing ability to re-imagine a piano work, clothing it in instrumental color, and many of his orchestral works began as piano pieces.

The Mother Goose Suite is one of these: in its original piano duet form it was a gift to the piano-playing children of a friend, and it radiates affection for children and the world of childhood. It also reveals Ravel’s fondness for dance forms and a fascination with the past. As an orchestral work, these delicate miniatures create brilliant, jewel-like impressions.

With his Piano Concerto in G major, Ravel set out to be brilliant rather than profound and the musical impressions race by, from references to past traditions to the “latest thing,” jazz. The dreamy slow movement begins with a long solo for the pianist, but this is a concerto in which everyone is allowed their moment in the spotlight.

The ferociously difficult Piano Concerto for the Left Hand was commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, who’d lost his right arm in World War I. It, too, reveals a distinct jazz influence, so it’s hardly surprising that it has an important place in the repertoire of a soloist who, while studying classical piano in an academy for talented children, taught himself jazz piano from his parents’ record collection.

The piano sits at the heart of the first three works in today’s concert, but the program ends with Boléro—music that could only have been written for orchestra. Ravel described it as “orchestral tissue without music,” and if he is right then this is not insult but an acknowledgement of the sonic power of the orchestra as an instrument.

Mother Goose Suite

Maurice Ravel

Born 1875, Ciboure, France

Died 1937, Paris

Maurice Ravel composed his Mother Goose piano duet as a gift to Mimi and Jean Godebski, the piano-playing children of friends, although they were too shy to present its premiere in 1910. The following year, encouraged by his publisher Durand, Ravel orchestrated his “five childlike pieces” as a concert suite before expanding them into an accompaniment for a ballet.

Inspired by baroque fairy tales (the title comes from Charles Perrault’s 1697 book, Contes de ma Mère l’Oye or “Tales of Mother Goose”), Ravel created a set of miniatures modeled on the baroque dance suite. Disguised as once-upon-a-time stories, a slumbering pavane, a bustling march from the Far East, a slow waltz, and a magical sarabande take their turn. Only the constantly shifting meter of Tom Thumb’s bewildered wanderings precludes the second movement from joining the others in the ballroom.

The tiny Pavane for the Sleeping Beauty sets the scene with slow and courtly music of perfect simplicity as Ravel evokes the poetry of childhood. His musical characterizations are both sophisticated and direct. Cheeping birds gobble bread crumbs dropped by Tom Thumb in Petit Poucet, but watch carefully—in addition to the expected bird sounds from the woodwind section, Ravel also creates flute-like whistling sounds with a solo violin playing harmonics.

The story Laideronnette, Empress of the Pagodes is from a collection by Perrault’s contemporary, Comtesse d’Aulnoy. A beautiful princess has been made ugly by a wicked witch—hence her name, which means “Ugly Little Girl.” With a Green Serpent (once a handsome prince), she sails to the land of the Pagodes, a population of tiny articulated figurines, with bodies made of jewels and porcelain, playing instruments made from the shells of walnuts and almonds. In its original version, Laideronnette bathes to dainty motifs played on the piano’s black keys, giving the music its characteristic Javanese sound. Ravel’s brilliant reworking for orchestra amplifies the effect with layers of delicate colors.

Conversations of Beauty and the Beast is a waltz inspired by Erik Satie and it’s sometimes referred to as the “fourth Gymnopédie.” In this musical telling of a story by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont (1757), the elegant clarinet is cast in the role of Beauty while a grumbling contrabassoon part represents the Beast.

The Enchanted Garden became the apotheosis of the ballet, with a scenario devised by Ravel himself: Prince Charming finds the Princess asleep in the garden; she awakens with the rising sun and there is a joyous fanfare as the other characters gather around her and the Good Fairy blesses them all. Again, Ravel’s skill as a miniaturist is revealed, building in mere minutes from a serene opening to the resplendent climax.

Adapted from a note by Yvonne Frindle © 2002

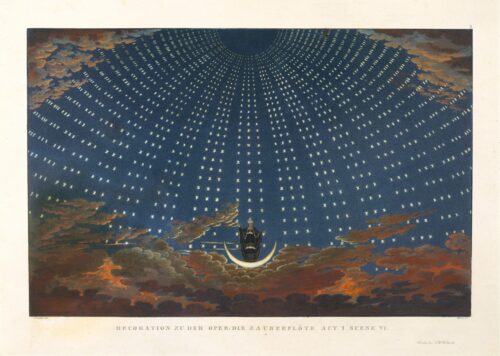

“Reclining upon a bed was a princess of radiant beauty.” Illustration by Gustave Doré for “La Belle aux bois dormant” in the 1862 edition of Les Contes de Perrault.

| First performance | Two young students (Jeanne Leleu and Genevieve Durony) premiered the piano duet version at the Paris Conservatoire on April 20, 1910; the orchestrated movements were first heard in the Mother Goose ballet premiere on January 29, 2012 at the Théâtre des Arts, Paris, the orchestra of 32 musicians conducted by Gabriel Grovlez |

| First SLSO performance | December 19, 1913, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 3, 2018, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (one doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), 2 horns, timpani, percussion, harp, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 19 minutes |

Piano Concerto in G major

Ravel

Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G begins with the crack of a whip, startling the piccolo into action. The scene seems set for a race—or is it a circus? Before a minute has passed, each of the concerto’s chief characteristics has made a fleeting appearance: joyous brilliance, melancholy lyricism, lively virtuosity, classical economy, evanescent orchestral color, a hint of American jazz, and a trace of Ravel’s native Basque country.

Maurice Ravel said his goal was to write a “genuine concerto”—a brilliant work, highlighting the virtuosity of the soloist. He was, in part, reacting to the kind of symphonic concerto “conceived not for but against the piano” (here he mentions Johannes Brahms). Instead he took as his musical guides W.A. Mozart and Camille Saint-Saëns, whose piano concertos he especially admired.

Mozart is present not only in the collaborative relationship between the soloist and orchestra, but in the classically proportioned orchestra and the way Ravel places the woodwinds in high relief. Saint-Saëns emerges in neoclassical forms and in the way the musical materials seem calculated to delight.

Also in the spirit of Mozart and Saint-Saëns, Ravel had intended the concerto for his own use. But unlike those composers, Ravel was no keyboard virtuoso, and it was Marguerite Long who gave the premiere. Ravel may not have been much of a pianist, but he was a virtuoso of the orchestra, and in this concerto the orchestra is featured as much as the piano. After the piccolo and trumpet introduce the spirited opening theme, the English horn escorts us into Spain, accompanied by languid strumming from the piano. The clarinet introduces the first of a series of jazz-inspired gestures that suggest George Gershwin. Listen for the distinctive qualities of high bassoon and muted trumpet; listen for the harp, which is given the first cadenza, ahead of the soloist!

The slow second movement (Adagio assai) begins with piano alone, playing one of Ravel’s most expressive and finely crafted melodies. Ravel claimed it nearly killed him, but there’s no evidence of the painstaking effort that went into sculpting this perfectly poised music. Ravel creates a feeling of impulse by superimposing a stately sarabande dance rhythm in the right hand above a slow waltz in the left. Once the orchestra enters, the mournful tones of the English horn lead a wistful and tender dialogue.

The third movement—a whirlwind presto barely four minutes long—is launched with a drum roll and a fanfare. We’re back in the world of races and circuses—the world of Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka and Erik Satie’s Parade. The music plays out a game, said Long, in which two themes are pursued between soloist and orchestra. The Presto is more overtly jazzy than the first movement, with piercing clarinet flourishes and sliding trombones. Through all this the piano darts and weaves until the dazzling movement is brought to a sudden and abrupt end, exactly as it began.

Yvonne Frindle © 2023

| First performance | January 14, 1932, by the Lamoureux Orchestra in Paris, the composer conducting, with Marguerite Long as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | February 17, 1945, Leonard Bernstein conducting from the piano |

| Most recent SLSO performance | January 14, 2023, Cristian Măcelaru conducting, with Alice Sara Ott as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; flute, piccolo, oboe, English horn, clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpets, trombone, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 23 minutes |

Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Ravel

Before they were musical collaborators, Maurice Ravel and Paul Wittgenstein served on opposing sides of World War I. Ravel, nearly 40, hoped to be a pilot in the French Air Force but ended up as a supply vehicle driver; Wittgenstein, who at 26 had recently made his solo debut as a pianist, was called up to serve in the Austro-Hungarian Army. In August 1914, during the Battle of Galicia in southern Poland, Wittgenstein was shot in the elbow. When he woke up, he learned that the doctors had amputated his right arm, and that during the surgery, the Russians had seized the field hospital and taken everyone prisoner. He was treated at a POW hospital in Siberia, where he resolved to resume his musical career against all odds. First he drew a keyboard on a crate, imagining how he could rework well-known pieces for left hand alone. Then for a few lucky months, he was interned at a hotel where he could practice on an upright piano, but he was eventually transferred to a fearsome gulag that had once held the exiled Fyodor Dostoevsky. In November 1915, he was repatriated to Austria in a prisoner exchange.

Wittgenstein’s wartime ordeal—filled with rats, lice, malnutrition, and typhus—was worlds apart from the comfort and privilege of his upbringing. His father, Karl Wittgenstein, made a fortune in steel—the “Austrian Andrew Carnegie.” Their palatial home was furnished with seven grand pianos, and the children became deeply involved with music, art, and mathematics. Paul’s brother Ludwig Wittgenstein, was a savant who gave away his fortune and became one of the 20th century’s most important philosophers. Their sister Margaret was painted by Gustav Klimt and analyzed by Sigmund Freud. But the family was often dysfunctional and visited by tragedy—three older brothers each committed suicide.

In the decades after the war, Paul used his inherited wealth to commission left-hand pieces from Maurice Ravel, Richard Strauss, Benjamin Britten, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Paul Hindemith, and Sergei Prokofiev. Despite working with such distinguished composers, he took a surprisingly transactional approach, treating the resulting works as his own personal property. This led to conflict with Ravel, who was incensed by Wittgenstein’s requests and criticisms of the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand.

In August 1929, at their first meeting to work through the piece-in-progress, Wittgenstein objected to a long solo passage, remarking, “If I had wanted to play without the orchestra I would not have commissioned a concerto!” Three years later, when Ravel heard Wittgenstein perform the finished piece in Vienna, he was shocked that the soloist had seriously altered the score, reworking entire passages. “But that is not [what I wrote] at all!” Ravel objected. “What you composed does not sound right,” Wittgenstein retorted. Ravel demanded that Wittgenstein play only what was written, but the pianist countered: “No self-respecting artist could accept such a condition. All pianists make modifications, large or small, in each concerto they play.” Eventually the argument cooled and Wittgenstein came to see it as a “great work” without any changes, but it was never a genial collaboration.

The finale, a synthesis of the preceding three movements, brings it all back home. As promised by its Allegro con fuoco tempo marking, it is fast and fiery. But beyond the razzle-dazzle pyrotechnics, the finale radiates an elemental life force. This vital energy transcends national identity, maybe even identity itself. It doesn’t live anywhere. It just lives.

The Music

With clever use of the sustain pedal, even a single hand on the piano can create layers of texture and both melody and accompaniment at the same time. In a 1931 interview for London’s Daily Telegraph, Ravel described the Concerto for the Left Hand as “very different” from the G major concerto:

It contains a good many jazz effects, and the writing is not so light. In a work of this kind it is essential to give the impression of a texture no thinner than that of a part written for both hands. For the same reason I resorted to a style which is much nearer to that of the more solemn kind of traditional Concerto. A special feature is that after a first part in this traditional style, a sudden change occurs and the jazz music begins. Only later does it become evident that this jazz music is really built on the same theme as the opening part.

The growling introduction features one of the few contrabassoon solos in the orchestral repertoire. This grows into a fanfare, which leads to the extended solo piano passage that Wittgenstein initially objected to. The piece is both contemplative and brilliant in turn; a climactic stretch is reminiscent of Ravel’s Boléro from 1928, before a cadenza and a tumultuous—but finally victorious—coda.

Abridged from a note by Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | January 5, 1932, the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Robert Heger, with Paul Wittgenstein as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | December 11, 1942, Vladimir Golschmann conducting, with Robert Casadesus as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | April 14, 2012, David Robertson conducting, with Leon Fleisher as soloist |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, E-flat clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 19 minutes |

Boléro

Ravel

Dancer-entrepreneur Ida Rubinstein wanted to create a Spanish ballet. The choreographer would be Bronislava Nijinska (Vaslav Nijinsky’s sister) and for the music Rubinstein invited Ravel to orchestrate Isaac Albéniz’s piano work Iberia. But one of Ravel’s friends pointed out that such a ballet was already in the making (it was 1928) and that neither he nor Rubinstein would be able to obtain the necessary permissions to repeat the exercise: the ballet, the scenario, and Albéniz’s music were “covered by a network of agreements, signatures, and copyrights that could not be broken.”

Instead, Ravel came up with something original and “rather unusual.” He claimed it had no true form, no development, hardly any modulation and a vulgar theme, but plenty of rhythm and orchestration. Boléro was born.

For this exhilarating music, Ida Rubinstein conceived a tableau in the manner of the Spanish painter Francisco Goya: a moody interior, in which a flamenco dancer performs a stylized bolero on a table “amid the encouragement and impassioned quarrels of the spectators,” a languid beginning building to a representation of inflamed desire.

Ravel accepted her interpretation, but its frenzied sensuality was not what he’d had in mind. His own vision for the scenario had included factory assembly lines to mirror the mechanistic repetition and chain-like linking of themes in the music. (Later, in 1941, the choreographer Serge Lifar created a new version with a factory setting that underlined “the mechanical side of the music’s construction.”) And it was Ravel’s conception that prompted perhaps the most famous disclaimer in music:

I am particularly desirous that there should be no misunderstanding as to my Boléro. It is an experiment in a very special and limited direction… Before the first performance, I issued a warning to the effect that what I had written was a piece lasting 17 minutes and consisting wholly of orchestral tissue without music…

Ravel goes on to point out that there are no contrasts, the themes are “impersonal,” and there is “practically no invention except in the plan and the manner of the execution.” And he was not exaggerating when he described Boléro as one long crescendo: like a musical machine, the work builds inexorably in color, texture and sheer volume—gathering steam from the voice of a solitary side drum to the overwhelming effect of the full orchestra. Whatever Ravel might say, Boléro is a tour de force.

Yvonne Frindle © 2012/2025

| First performance | November 22, 1928, by Ballets d’Ida Rubinstein, Walther Straram conducting the Paris Opera Orchestra at the Palais Garnier; the first concert performance took place in New York on November 14, 1929, Arturo Toscanini conducting the New York Philharmonic |

| First SLSO performance | February 28, 1930, Eugene Goossens conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 7, 2020, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), piccolo, 2 oboes (one doubling oboe d’amore), English horn, 2 clarinets (one doubling E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, celesta, strings |

| Approximate duration | 16 minutes |

Artists

Kirill Gerstein

Among Kirill Gerstein’s noteworthy recordings is The Gershwin Moment with the SLSO and David Robertson, including special appearances from singer-songwriter Storm Large and vibraphonist Gary Burton. It’s representative of his fascination for musical discovery combined with boundless curiosity, imagination, and virtuosity. As a pianist, curator, educator, musical leader, and artistic collaborator, his exploration of resonant themes across a vast spectrum of repertoire—from Baroque suites and Classical concertos to contemporary creations, jazz, and cabaret—has nourished relationships with many of the world’s leading orchestras, conductors, instrumentalists, singers, composers, and festivals, as well as recording labels and media platforms.

Most recently, he was Artist-in-Residence with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Spotlight Artist with the London Symphony Orchestra, and Resident Artist at the Festival Aix-en-Provence. He also curated the Busoni and His World concert series at Wigmore Hall, London, and at Tanglewood, performed 1920s Berlin cabaret songs with HK Gruber. In 2023, he released an album celebrating Rachmaninoff’s 150th anniversary with the Berliner Philharmonic, and his 2024 media project, Music in Time of War, pairs music by Debussy and Vardapet Komitas.

A champion of music of our time, he has commissioned works from Timo Andres, Chick Corea, Alexander Goehr, Oliver Knussen, and Brad Mehldau, among others. And since premiering Thomas Adès’s Piano Concerto in 2019, he has performed it more than 50 times and recorded it with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by the composer (2020 Gramophone Award). Next season he will premiere a new concerto written for him by Francisco Coll.

Highlights of this season include Messiaen’s From the Canyons to the Stars with Simon Rattle (Musikfest Berlin); marking Ferrucio Busoni’s centenary with performances of his Piano Concerto (Berlin Philharmonic, Orchestre National de France, BBC Symphony Orchestra, and Gulbenkian Orchestra, Lisbon); Schoenberg’s Ode to Napoleon paired with Beethoven’s “Emperor” Concerto (Wiener Symphoniker); return engagements in San Francisco, Pittsburgh, and Atlanta; and recitals in Carnegie Hall, the Vienna Musikverein, Berlin’s Boulez Saal and Wigmore Hall. He also play-conducts Beethoven concertos (Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Orchestre de Chambre de Paris, and Czech Philharmonic) and Rhapsody in Blue (Budapest Festival Orchestra).

He is Professor of Piano at Berlin’s Hanns Eisler School of Music and on the faculty of Kronberg Academy, where his online seminars featuring conversations with leading artistic minds have reached more than 150,000 viewers. He also coaches at the Verbier Festival Academy and at IMS Prussia Cove.

Born in 1979 in Voronezh, Russia, Kirill Gerstein attended a music school for gifted children and taught himself to play jazz by listening to his parents’ records. Following a chance encounter with Gary Burton in St. Petersburg, he was invited to study at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, and at 16, he completed his undergraduate and graduate degrees at New York’s Manhattan School of Music, followed by studies with Dmitri Bashkirov (Madrid) and Ferenc Rados (Budapest). In 2010 he won the 10th Arthur Rubinstein Competition, and received the Gilmore Artist Award and an Avery Fisher Career Grant. He received an Honorary Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the Manhattan School of Music in 2021.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.