Stravinsky and Debussy (January 10-11, 2026)

Program

January 10-11, 2026

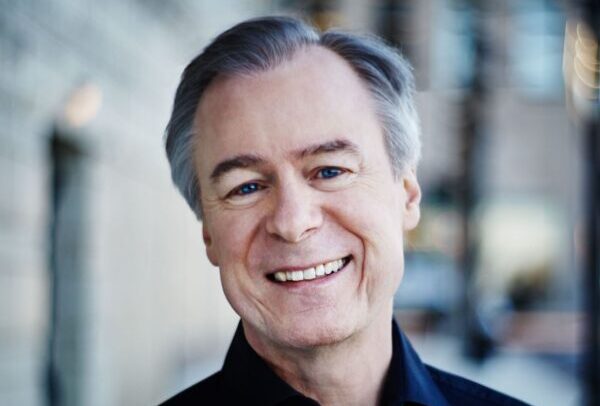

- Stéphane Denève, conductor

- Saint Louis Dance Theatre

- Kirven Douthit-Boyd, artistic director

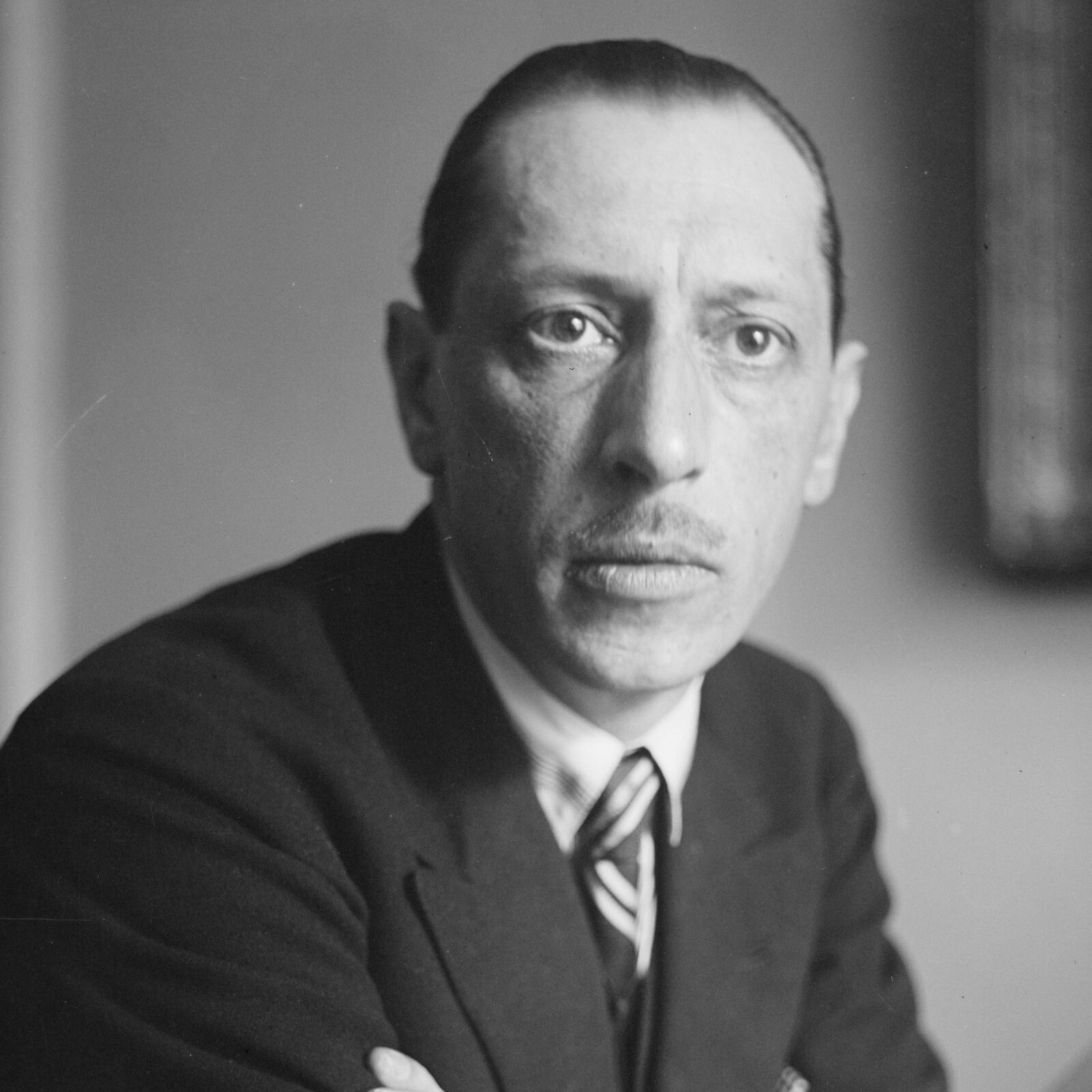

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

- Concerto in E flat (Dumbarton Oaks)

- Tempo Giusto –

- Allegretto –

- Con moto

Igor Stravinsky

- Pulcinella Suite

- Sinfonia (Ouverture)

- Serenata –

- Scherzino – Allegro – Andantino

- Tarantella –

- Toccata

- Gavotta con 2 variazioni

- Vivo

- Minuetto – Finale

Saint Louis Dance Theatre

Kirven Douthit-Boyd, choreographer

Intermission

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

- Jeux (Games) – Poème dansé

Albert Roussel (1869-1937)

- Suite No. 2 from Bacchus et Ariane, Op. 43

- Prelude. Ariadne’s Awakening –

- Ariadne and Bacchus –

- Bacchus Dances Alone

- The Kiss – The Dionysian Spell –

- The Bacchic Procession –

- Dance of Ariadne

- Dance of Ariadne and Bacchus –

- Bacchanale – The Coronation of Ariadne

Music in Motion

The choreographer George Balanchine once said that “dancing is music made visible.” Visible music isn’t something you’d normally experience in an orchestral concert, but this week’s collaboration with Saint Louis Dance Theatre provides a dynamic exception.

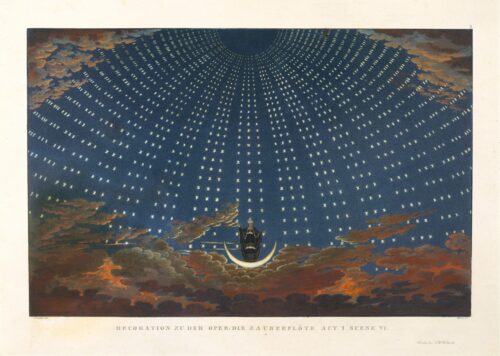

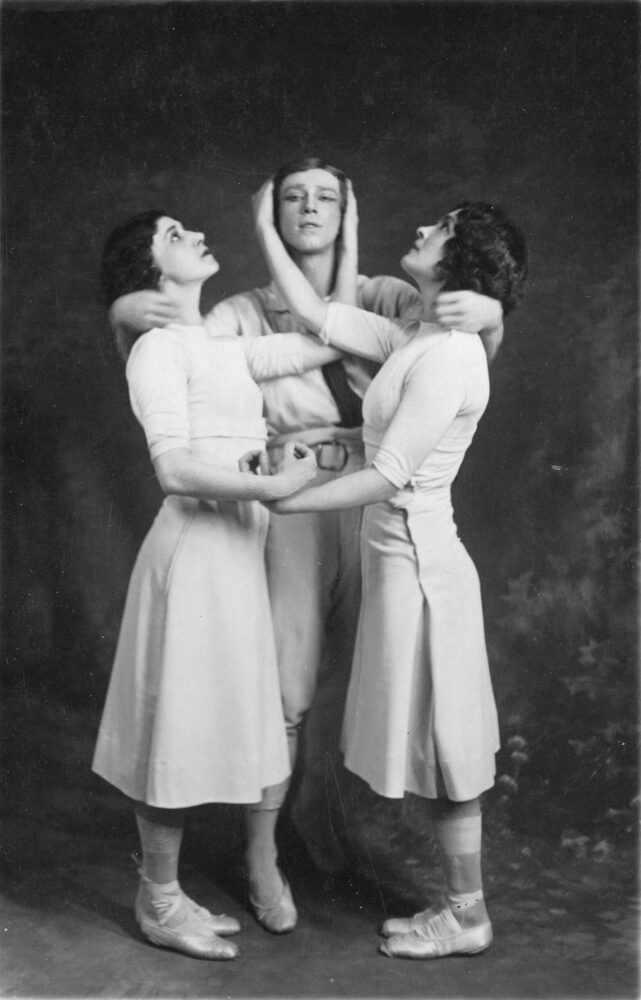

Stéphane Denève’s program brings together three ballet scores from early 20th-century Paris—a tribute to Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and its legacy. The earliest of these is Claude Debussy’s Jeux (Games), which he thought of as a “danced poem.” The ballet Vaslav Nijinsky made to it in 1913 has been reconstructed and reinterpreted, but Jeux survives chiefly as a concert work, in part because it calls for a 94-piece ensemble that would cause most modern orchestra pits (and ballet company music budgets) to bulge at the seams.

Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella ballet score was a more compact creation—drawing its musical forces and stylistic language from the world of the 18th century. And in this weekend’s performances, our musicians share the stage with the dancers of STLDT. Kirven Douthit- Boyd’s Pulcinella is a visibly new choreographic creation, but like Stravinsky before him, Douthit-Boyd blends contemporary vision with echoes of a classical vocabulary.

Stravinsky also provides the opening work, a baroque-inspired concerto composed for the wedding anniversary in 1938 of St. Louis native Robert Woods Bliss and his wife Mildred. At the other end of the program is the second suite (or rather, Act II) from Albert Roussel’s 1931 ballet score Bacchus et Ariane. Completed a decade

after Pulcinella, Bacchus et Ariane was created by Serge Lifar (a former Ballets Russes principal) for the newly rejuvenated Paris Opera Ballet. Like Jeux, the huge orchestra is given music that is often extremely delicate, making its surging climaxes all the more potent.

This concert offers an abundance of visual and aural delights—literal music in motion—and Debussy’s viewpoint applies: “There is no theory: you just have to listen. Pleasure is the rule.”

“Dumbarton Oaks” Concerto

Igor Stravinsky

Born 1882, Oranienbaum near St. Petersburg, Russia

Died 1971, New York City

This concert begins with a modern take on the baroque concerto grosso genre—music that sets a small group of soloists (the concertino) against a larger ensemble (the ripieno). “Concerto in E flat” is the title and Johann Sebastian Bach is the direct inspiration: Stravinsky described it as “a little concerto in the style of the Brandenburg Concertos.”

Stravinsky’s Concerto has a nickname, too, and it tells us how he came to compose it. Robert Woods Bliss, a St. Louis-born diplomat, and his wife Mildred were generous patrons of the arts, and they commissioned Stravinsky to compose a piece “of Brandenburg Concerto dimensions” for their 30th wedding anniversary, which fell due in 1938. Stravinsky then went to visit them, at Dumbarton Oaks, near Washington, DC. This Georgian-style mansion was set in exquisite gardens and its Music Room, still used for concerts today, was decorated in the Renaissance style. (The estate was presented to Harvard University in 1940 and would become the setting, in 1944, for a conference between the US, UK, Soviet Union, and China that led to the establishment of the United Nations.)

Bach’s Brandenburg concertos delight listeners by varying the groups of solo instruments, winds, brass, strings. Here it’s as if Stravinsky has condensed all six Brandenburgs into one, treating his 15 instrumentalists as virtuoso soloists—sometimes bringing different players in and out of the texture for spotlight moments, sometimes weaving them together in intricate combinations.

But the Brandenburg concerto that was probably uppermost in Stravinsky’s mind was the one he’d conducted in Cleveland in 1937, just a few months before he received the commission: Concerto No. 3, scored for three violins, three violas, three cellos, and harpsichord. In this concerto, Bach separated the two fast movements with an embryonic “slow movement”—just two chords. Stravinsky’s concerto is in three continuous movements, but at each transition point there is slower, chordal music. The music echoes Bach, and the parallels are clear, especially in the driving pulse of the first movement. But despite the baroque models, this spirited Concerto shows how Stravinsky, even at his most “neoclassical,” remains unmistakably himself.

The first (private) performance of the concerto was scheduled for May 8, 1938, in the grand Music Room at Dumbarton Oaks. Stravinsky was to have conducted, but he was undergoing a cure for tuberculosis near Geneva, so at his wish, the great teacher of composers, Nadia Boulanger, conducted instead. The name “Dumbarton Oaks” is fittingly attached to this concerto, since Stravinsky’s architectural conception of the music may have been partly inspired by the layout of the gardens.

Adapted from a note by David Garrett © 2010

| First performances | May 8, 1938, conducted by Nadia Boulanger at Dumbarton Oaks; the public premiere followed in Paris on June 4, the composer conducting; Stravinsky also conducted the first performance in St. Louis on March 22, 1950 (University of Illinois Sinfonietta) |

| First SLSO performance | September 16, 1971, conducted by Walter Susskind |

| Most recent SLSO performance | November 14, 2020, conducted by Stéphane Denève |

| Instrumentation | flute, clarinet, bassoon, 2 horns, 3 violins, 3 violas, 2 cellos, and double basses |

| Approximate duration | 15 minutes |

Pulcinella Suite

Igor Stravinsky

Born 1882, Oranienbaum near St. Petersburg, Russia

Died 1971, New York City

The Pulcinella music in this concert began life in 1920 as a one-act “ballet with song,” about 40 minutes long and with three vocal soloists joining the orchestra in the pit. Stravinsky then made a concert suite. This weekend, the suite comes full circle, with the dancers of Saint Louis Dance Theatre and new choreography by Kirven Douthit-Boyd. It’s a fitting collaboration, since the history of Pulcinella is a tale of transformations, reflecting Stravinsky’s view of tradition as “an heirloom, a heritage that one receives on condition of making it bear fruit before passing it on to one’s descendants.”

This particular heirloom has its origins in 18th-century Italy with the tradition of commedia dell’arte (street comedy based on stock characters) and violinist-composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, a favorite of Sergei Diaghilev’s. For its first “fruiting,” designer Pablo Picasso and choreographer Léonide Massine were added to the mix and Stravinsky was invited to arrange a collection of pieces Diaghilev had assembled. Stravinsky had a low opinion of Pergolesi’s music and thought Diaghilev “must be deranged.” Closer examination brought a change of heart: “I looked, and I fell in love.” Later, Stravinsky would quip that his favorite music by Pergolesi was “my Pulcinella.”

Pergolesi?

As it happens, some of the “unpublished fragments” Diaghilev had unearthed in Italian libraries weren’t by Pergolesi at all, but by less well-known figures: Domenico Gallo (to whom we owe the first two movements in the suite), Alessandro Parisotti, Carlo Ignazio Monza, and the Dutch diplomat Count van Wassenaer. But on opening night,Pulcinella was billed as “Music by Pergolesi, arranged and orchestrated by Igor Stravinsky.” It was the first publisher who reversed the attribution: Music by Stravinsky, after Pergolesi. The truth falls somewhere in the middle. Many, encouraged by the composer’s own writings and the ballet’s first conductor Ernest Ansermet, consider the score a “recomposition,” taking its sources as a point of departure. Others, such as Richard Taruskin, characterize it as a “freewheeling and imaginative arrangement,” in other words, precisely what Diaghilev had ordered.

Regardless, Pulcinella marks an early excursion into neoclassicism— Stravinsky looking backwards to discover the past, while also looking in the “mirror” of a creative present. In other words, 1920s taste provided a lens for interpreting these 18th-century pieces. The obvious nod to the past is an orchestral formation that resembles a baroque concerto grosso: a solo group (concertino) including a string quintet is contrasted with the full ensemble (ripieno). But only Stravinsky could have devised the slapstick comedy of the Vivo movement (pairing a trombone and a double bass for an orchestral “farting” effect) and overall, there’s a modern astringency to the colors and harmonic twists.

Dancing Pulcinella

Jumping forward a century, Douthit-Boyd introduces a new “mirror” for his own look at the past. Instead of Massine’s historical scenario and stock characters (Pulcinella, Pimpinella, and the rest), this new Pulcinella riffs on the idea of commedia dell’arte. “There’s no narrative,” he explains, “but there’s a lead character—an unnamed ‘Pulcinella’— who guides us from section to section.” Closer to home, the popular vaudeville origins of Powell Hall—spectacle, comedy and pure entertainment—provided their own inspiration.

The neoclassicism of Stravinsky’s score also bears fruit in the choreography for the company’s classically trained dancers. “Sometimes it’s a challenge,” explains Douthit-Boyd, “because whenever I get into the classical music realm, I tend to stray towards the more classical steps. But we’re a contemporary dance company and we’re staying true to that.” At the same time, he points out, there will be moments, such as the Tarantella and the Finale, when recognizable vocabulary emerges in a way that’s fun and interesting.

Yvonne Frindle © 2008/2026

| First performance | The Pulcinella ballet was first performed by the Ballets Russes in Paris on May 15, 1920, conducted by Ernest Ansermet; the concert suite was premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra on December 22, 1922, conducted by Pierre Monteux |

| First SLSO performance | February 27, 1931, conducted by George Szell |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 9, 2021, conducted by Stéphane Denève |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, trumpet, trombone, concertino string quintet (2 violins, viola, cello, double bass) and a small string orchestra (8 violins, 4 violas, 3 cellos, 3 double basses) |

| Approximate duration | 24 minutes |

Jeux, a danced poem

Claude Debussy

Born 1862, Paris, France

Died 1918, Paris

Imagine the scene: the music of Jeux steals into the auditorium, dreamy and ambiguous; the curtain rises on an empty park (cue the principal clarinet and a gracefully playful mood). Two minutes in, a tennis ball is thrown onto the stage (a high, shivering chord), followed by a young man, racket held high, leaping across the stage (Vaslav Nijinsky, famous for his astonishing jumps; two harpists running their hands across the strings). Jeux (Games) takes us into an enigmatic, twilight world. Its love-triangle (one boy, two girls) involves flirtation, playfulness, fleeting jealousies, and casual ecstasy. The setting is a tennis court, giving a double meaning to the “games” of the title.

The ballet was not well-received in 1913, and it was further eclipsed by the premiere of The Rite of Spring two weeks later. Jeux must have puzzled the audience: the contemporary sport-inspired scenario; dancers in street clothes; Nijinsky’s experimental, stylized choreography; Debussy’s groundbreaking score.

Debussy had been unhappy with Nijinsky’s “ugly” and angular choreography for L’Après-midi d’un faune (Afternoon of a Faun) in the 1912 Ballets Russes season. But when he was approached with a commission for a new ballet, the money was tempting, and he was eventually drawn by the scenario’s “suggestion of something slightly sinister that the twilight brings.” Once again, however, the composer would be disappointed by “hideous” choreography that trampled his “poor rhythms like a weed.” Debussy sat out the premiere in the concierge’s office, smoking a cigarette.

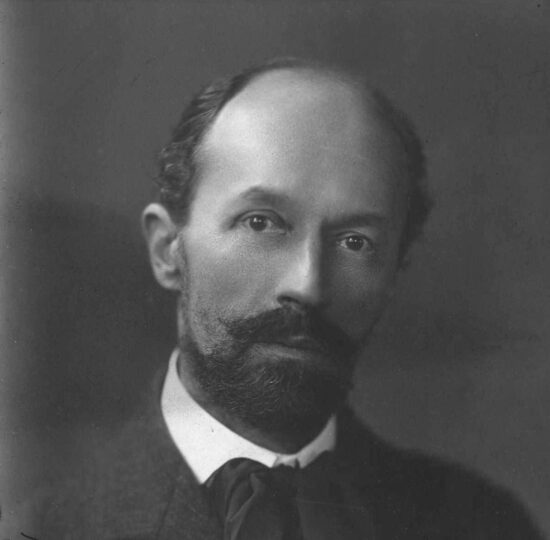

(credit: Studio Gerschel, 1913)

As a ballet, Jeux faded into obscurity. As music, it found a champion in the composer-conductor Pierre Boulez, who rescued it in the 1950s, applauding its “epochal significance, not only in the context of Debussy’s compositions, but also as a trailblazing directive force for all modern musical achievement.”

In Jeux, Debussy renounced traditional structures in favor of continuous development—a musical stream-of-consciousness that closely followed Nijinsky’s detailed stage directions. He also captured the elusive, dreamlike atmosphere of the scenario. In matters of harmony and tempo, the music is fluid and mercurial, the colors are shimmering and veiled, and the huge orchestra is used in subtle, weightless ways—Debussy said one would have to find an orchestra “without feet” to play it. But underpinning the innovations is an old-fashioned (and very balletic) idea: the ghost of a triple-time waltz—a rhythmic representation of the love triangle, perhaps, or as in La Valse by Ravel, a metaphor for pleasure and oblivion.

Yvonne Frindle © 2026

| First performance | Jeux was first performed on May 15, 1913 by the Ballets Russes in Paris, conducted by Pierre Monteux; the concert premiere followed in February 1914, conducted by Gabriel Pierné |

| First SLSO performance | February 19, 1965, conducted by Eleazar de Carvalho |

| Most recent SLSO performance | on tour at Carnegie Hall, New York City, on November 18, 2005, conducted by David Robertson |

| Instrumentation | 4 flutes (two doubling piccolo), 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, 2 harps, celeste, strings |

| Approximate duration | 17 minutes |

Bacchus et Ariane

Albert Roussel

Born 1869, Tourcoing, France

Died 1937, Royan, France

After the death of Sergei Diaghilev in 1929, his Ballets Russes troupe disbanded and Serge Lifar, one of the principal dancers, was invited to take over the Paris Opera Ballet and revive its declining fortunes. Among the many new ballets he created was Bacchus et Ariane, in which he also danced the role of Bacchus with Olga Spessivtseva as his partner, and for the music he turned to Roussel, then at the peak of his powers.

Albert Roussel had been a late starter. Like Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, his first career was as a naval officer. He began studying music when he was 25, and the piece that made his reputation, at age 44, was a one-act ballet called Le Festin de l’araignée (The Spider’s Feast, which the SLSO and Stéphane Denève performed in January 2024). You might think that for dancers, rhythm is the dominant concern, but melody is equally important for the momentum and buoyancy it provides. Roussel knew this and the neoclassical style of his second ballet, Bacchus et Ariane, played to his professed strengths: “directness of rhythm” and “clarity of melodic line.”

The ballet’s scenario is based on Greek myth and picks up after the Athenian hero Theseus has slain the Minotaur and escaped the monster’s labyrinth with the help of Ariadne, daughter of the King of Crete. Returning to Athens, they stop off on the island of Naxos, where they encounter the hedonistic god of wine, Dionysus (Bacchus to the Romans, and the French). By the end of Act I, Theseus has sailed away, abandoning Ariadne. In Act II, Ariadne is rescued by Bacchus, who makes her immortal with a kiss and brings the barren island to life with satyrs, maenads (unruly nymphs), and flourishing vines.

Although the internal logic of the score gives the impression of continuous, symphonic development, Roussel also follows the traditions of 19th-century ballet, providing distinct solos and duets, ensemble numbers, and mimed scenes that advance the narrative. As with Debussy’s Jeux, stage directions for these are written into the published score, but Roussel goes beyond slavish illustration. Each act stands on its own as a coherent musical work, which happily allowed for the creation of two concert “suites” that make no substantive changes to the music.

A Myth in Sound

The prelude to Act II depicts Ariadne asleep with a tender viola solo. As the curtain rises, she awakens to what has been identified as a possible act of homage, a theme borrowed from Le Soleil matinal (The Morning Sun) by Roussel’s teacher Vincent d’Indy. Ariadne realizes she has been abandoned, and the now erratic and increasingly distressed music builds as she prepares to throw herself off a cliff into the waves. Instead she falls into the arms of Bacchus and they resume their sumptuous dream-dance from Act I. Bacchus then dances alone to puckish, animated music suggestive of Richard Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel.

The couple’s ecstatic kiss is pervaded by the rich colors of violas and horns, and in turn the rippling flutes and cascading violins of “Dionysian enchantment.” Bacchus’ wild followers arrive to an emphatic three- legged “march” and present Ariadne with a golden cup of wine. Her seductive dance is accompanied by an alluring violin solo. Bacchus joins in with a hypnotic rhythmic pattern of 3+3+4 beats (10/8 time)—this is not a romantic pas de deux, but a prelude to the brilliant bacchanale for the full company. In the final, thrilling minute, Bacchus crowns Ariadne with stars plucked from the constellations of the heavens. The brass provide some underlying solemnity, but the mood is undeniably exhilarating. As Roussel’s first English biographer suggested: we’re left thinking Ariadne was in for a much better time than she would have had if Theseus had taken her with him.

Yvonne Frindle © 2020/2026

| First performance | Bacchus et Ariane was first performed by the Paris Opera Ballet on May 22, 1931, conducted by Philippe Gaubert; Pierre Monteux conducted the first performance of Suite No. 2 on February 2, 1934, also in Paris |

| First SLSO performance | October 17, 1952, conducted by Vladimir Golschmann |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 9, 2007, conducted by Stéphane Denève |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, 2 harps, celeste, strings |

| Approximate duration | 20 minutes |

Artists

Kirven Douthit-Boyd

Kirven Douthit-Boyd began his formal dance training at the Boston Arts Academy in 1999 and as a member of Boston Youth Moves before studying as a fellowship student at the Ailey School and on scholarship at the Boston Conservatory. He holds an MFA in Dance from Hollins University. He began his professional career with Ailey II (2002–04) and performed at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival with Battleworks Dance Company (2003). In 2004, he joined the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, where he performed internationally for 11 years. In 2010, he performed at the White House in a Judith Jamison tribute hosted by First Lady Michelle Obama.

In 2015, he joined COCA (Center of Creative Arts) as Co-Artistic Director of Dance with his husband, Antonio Douthit-Boyd. He was appointed Artistic Director of the Big Muddy Dance Company in 2022, leading its 2024 relaunch as Saint Louis Dance Theatre. His choreography has been commissioned by Ailey II and numerous schools and universities. He is also an ABT® Certified Teacher and has completed Horton Pedagogy studies under Ana Marie Forsythe.

His honors include the Black Theater Alliance Award, Next Generation in Leadership Award (Freedom House, Boston), Apollo Award (Boston Arts Academy), Excellence in the Arts Award (Arts and Education Council of St. Louis), and Dance Teacher Magazine Award. His leadership at STLDT blends narrative modernism and contemporary physicality, positioning the company with both national ambition and deep community connections.

Saint Louis Dance Theatre

Saint Louis Dance Theatre is blazing new trails by interweaving the Gateway City’s storied legacy into boundary-pushing contemporary performances. Combining world-class artistry with a bold vision, the company champions inclusivity, collaboration, and artistic excellence. It was founded in 2010 by Paula David as the Big Muddy Dance Company, presenting its first full production in 2011. Since then, STLDT has increased its membership to 16 dancers, presenting three full productions each season, touring regionally, and offering education and outreach programs. Now under the artistic direction of Kirven Douthit-Boyd, the company has commissioned more than 95 works and completed over 400 performances, with guest artists including such luminaries as Jiří Kylián, and has established itself as the premier professional dance company in St. Louis.

STLDT has previously collaborated with the SLSO for Anna Clyne’s DANCE for cello and orchestra (2021) and Adam Schoenberg’s Picture Studies (2023), both choreographed by Douthit-Boyd.

stldancetheatre.org

Pulcinella casts

Demetrius Cast (Jan 10)

| Sinfonia | Full Company |

| Serenata | Molly Rapp and Will Brighton |

| Scherzino | Dave McCall, Jada Vaughan, AJ Joehl, Nyna Moore and Ensemble |

| Tarantella | SenSaSheri Maasera, Gillian Alexander, Julia Dawson, Julia Lucarelli |

| Toccata | Sergio Camacho, Keenan Fletcher |

| Gavotta | Arpège Lundyn, Miles Ashe, Angel Khaytyan |

| Vivo | Demetrius Lee |

| Minuetto | Nyna Moore, AJ Joehl, Jada Vaughan, Dave McCall, Sergio Camacho, Spencer Everett |

| Finale | Full Company |

Gillian Cast (Jan 11)

| Sinfonia | Full Company |

| Serenata | Molly Rapp and Will Brighton |

| Scherzino | Dave McCall, Jada Vaughan, AJ Joehl, Nyna Moore and Ensemble |

| Tarantella | Miles Ashe, Demetrius Lee, Angel Khaytyan, Keenan Fletcher |

| Toccata | Spencer Everett, Dave McCall |

| Gavotta | Julia Dawson, Sergio Camacho, Keenan Fletcher |

| Vivo | Gillian Alexander |

| Minuetto | Nyna Moore, AJ Joehl, Jada Vaughan, Dave McCall, Sergio Camacho, Spencer Everett |

| Finale | Full Company |

Shevaré Perry, costume designer