Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet (February 14–15, 2025)

Program

February 14–15, 2025

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Nikolai Lugansky, piano

Anna Clyne (b. 1980)

- PALETTE Concerto for Augmented Orchestra (World Premiere)

- Plum (Warm, sparse)

- Amber (Suspended in time)

- Lava (Erupting)

- Ebony (Propelling)

- Teal (Tranquil)

- Tangerine (Whimsical)

- Emerald (Expansive with ecstasy)

Jody Elff, sound design

Luke Kritzeck, lighting designer

Intermission

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18

- Moderato

Adagio sostenuto

Allegro scherzando

- Moderato

Nikolai Lugansky, piano

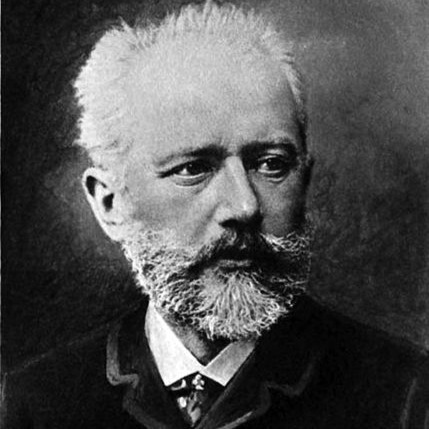

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

- Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

The Romantics

Whether you’re here with a loved one or here for the love of music, this evening’s program is our valentine to you. And Stéphane Denève has chosen two great Russian Romantics—composers we turn to for intensity of emotion and catharsis—to remind us that “with music we are never alone.”

Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff are united by more than their Russian nationality and place within the Romantic tradition. They are both melodists of the highest order, and you’ll be hard-pressed to decide which tune to leave humming tonight. Tchaikovsky struggled with what he called an “inability in general matters of form” (in other words, he didn’t compose like Beethoven). But he knew his strengths—“I write from an inward and irresistible impulse”—and it’s his melodic gift and dramatic instincts that make his Romeo and Juliet music so powerful, as he distills feelings of fury and passion, optimism and despair, and all the drama of a tragic love story into 20 minutes of genius.

Tchaikovsky composed, he said, “so that I may pour my feelings into my music.” In Rachmaninoff we find that same directness of expression, even when the music is abstract, with no story attached. Speaking about tonight’s piano concerto, Stéphane described Rachmaninoff’s music as “a pure expression of love—the ecstasy of love, the light of love.” It’s no wonder that Rachmaninoff’s melodies have been borrowed for cinematic love stories and pop ballads.

The Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff pieces are concert hall favorites. PALETTE by Anna Clyne is brand new. But if you heard us play Within Her Arms in November, you’ll know she’s another composer who writes deeply expressive and colorful music that engages emotions and the senses. PALETTE brings together (literal) colors and textures, finding common ground between art that we see and art that we hear, and we’re delighted to introduce it to you this Valentine’s weekend.

PALETTE

Anna Clyne

Born 1980, London, England

PALETTE is a concerto for augmented orchestra that, as the composer describes it, “explores the symbiosis between music and art.” And in the manner of works such as Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, it features sections and individual soloists from within the orchestra. The first movement, for example, features the piano and harp, while the second features the woodwinds.

The work is organized in seven five-minute movements—each one exploring a different hue and whose first letters provide the title of the work: Plum, Amber, Lava, Ebony, Teal, Tangerine, and Emerald. “As part of the creative process,” Clyne explains, “I have created a 30 by 30 inch painting for each movement— exploring gesture, texture, light and dark, color, and form—elements that also translate to music.”

The sumptuous rich tones of Plum, for instance, are heard as deep resonant tones and a cycling chorale. The vibrant red paint mixed with coarse ground pumice in the Lava artwork, is interpreted as explosive cascading figures in the strings, who are instructed to play “heavy into the string” to create a gritty quality. In Ebony, one of the featured instruments is the marimba with its wooden keys.

Augmenting the Orchestra

The use of the Augmented Orchestra (AO) allows Clyne to take sounds originating within the acoustic orchestra and electronically transform them, seamlessly integrating them into the listening experience. This electronic processing technique is made possible by custom software developed by sound designer Jody Elff. “Pitches will be shifted, notes and clouds of resonance are added,” explains Clyne, “all live in real time.”

Painting by Letters

Clyne’s approach to her inspiration paintings stemmed from her love of calligraphy, and the base layer of each painting is a large brush-stroke gesture outlining the first letter of the movement title. Over this, she added layers of paint, mixing in other substances to transform their textures: varnish for Amber, coarse ground pumice for Lava, tiny glass beads for Emerald, and so on.

Although the paintings themselves aren’t seen in the performance, their presence is felt through light. Expanding on her explorations of sight and sound, Clyne has collaborated with lighting designer Luke Kritzeck to create lighting cues for each movement—responding to and incorporating elements from the paintings. “The intention,” she writes, “is to envelop the audience to create a truly immersive and multisensory experience.”

Visit annaclyne.com/palette to see a gallery of the paintings.

About the Composer

Anna Clyne is one of the most in-demand composers working today, and earlier this season the SLSO and Stéphane Denève performed her most frequently heard orchestral work, Within Her Arms. She has been commissioned and presented by institutions including Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, MoMA, the Barbican, Philharmonie de Paris, Edinburgh International Festival, and Last Night of the Proms. Her music has been performed by orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic and London Philharmonic Orchestra, and she has held composer in residence appointments with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, Symphony Orchestra of Castilla y León, Philharmonia Orchestra, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, and the Trondheim, Baltimore, and Chicago symphony orchestras. Her collaborators span artforms and genres—including companies from LA Opera to San Francisco Ballet, and performers from Yo-Yo Ma to Björk.

Born in London, Clyne earned a music degree with honors from Edinburgh University in Scotland, where she studied with composer Marina Adamia, before completing a Master of Music degree at the Manhattan School of Music, where she studied with Julia Wolfe. She has received the Hindemith Prize and a Charles Ives Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and in 2015 was nominated for a Grammy Award for best contemporary classical composition. She is now based in New York.

Many of her works are inspired by other music, art, literature, and even found objects—her catalog includes pieces based on Scottish fiddle tunes, paintings by Mark Rothko, the philosophy of Leo Tolstoy, and a thrift-store violin.

Adapted from notes by Anna Clyne and Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | These concerts; in March, Stéphane Denève will conduct it again with the New World Symphony, of which he is Artistic Director |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (one doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 3 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano, strings, live electronic processing (Augmented Orchestra) |

| Approximate duration | 25 minutes |

Piano Concerto No. 2

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Born 1873, Semyonovo, Russia

Died 1943, Beverly Hills, California

For Sergei Rachmaninoff, his Second Piano Concerto represented much more than a career breakthrough. The simple fact that he had managed to compose something so substantial, after years of creative paralysis, was significant

in itself. The Piano Concerto No. 2 was an immediate popular success and remains among Rachmaninoff’s most frequently performed compositions. On the one hand, it’s a virtuoso showpiece: the composer himself, one of the most impressive pianists of this or any other age, gave the premiere on November 9, 1901. On the other hand, the concerto is remarkably subtle and transparent, attuned to the intimate frequencies of chamber music: at several points, the piano melts into the orchestra, becoming mere accompaniment, another textural ingredient.

Post-traumatic triumph

Mortified by harsh reviews of his First Symphony, in 1897, Rachmaninoff fell into a deep depression and although he remained busy as a pianist and conductor, he developed a bad case of writer’s block. The once prolific 24-year-old virtuoso turned to the internist and hypnotherapist Nikolai Dahl, who also happened to be a gifted violist. Part hypnotist, part life coach, Dahl helped Rachmaninoff triumph over self-doubt. (Many years later the grateful composer wrote, “New musical ideas began to stir within me—far more than I needed for my concerto.”)

In 1901 Rachmaninoff dedicated his Second Piano Concerto to Dahl; a year later he married their mutual friend, his first cousin, Natalia Satina, despite the heated objections of friends, family members, and authorities from the Russian Orthodox Church. The union was a happy one that endured until the composer’s death in 1943.

Along with self-affirming mantras—“You will begin your concerto; it will be excellent”—Dahl prescribed a final compositional exercise to cap off years of therapy: a new piano concerto. Rachmaninoff had dashed off his Piano

Concerto No. 1 while still a confident teenage prodigy. He performed the first movement once, in early 1892, and put it aside until late 1917. His Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, composed in late 1900 and early 1901, represents a hard-won triumph over the debilitating trauma that had sabotaged his creative drive. It catapulted him to fame as a concerto-composer; more than a century later, it remains an audience favorite.

What tune is that?

It’s a sure sign of success when your tunes enter popular culture, and by the 1940s the borrowings had begun. For the 1945 film Brief Encounter, scriptwriter Noël Coward specified the use of Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto.

More than simply background, the music functioned as a “character”—heard on the radio and then underpinning the flashback it triggers. Later, in The Seven Year Itch (1955), Marilyn Monroe “goes to pieces” every time she hears the concerto. Meanwhile, the big tune from the finale was lifted for “Full Moon and Empty Arms,” and in 1975 Eric Carmen borrowed from the concerto for “All By Myself,” which enjoyed renewed popularity when it was used in the film Bridget Jones’s Diary.

A closer listen

The concerto demands from the soloist speed, dexterity, and endurance, as well as sensitivity to subtle dynamic and rhythmic shadings. The first movement (Moderato) begins with the piano, which issues several chiming chords, each punctuated by a deep tolling note. After some intensifying exchanges with the orchestra, the piano erupts into a Russian folk-flavored motive; a secondary theme is lavishly lyrical. Later, a horn solo ventures into unexpected harmonic terrain, but the home key is quickly restored, and the movement ends with a resounding chord.

The Adagio sostenuto—the source of Carmen’s pop ballad—boasts a fearsome cadenza (making up for the lack of one in the first movement), with glittering passagework that subsides in Bach-like arpeggiated chords. A chamber-music intimacy prevails: delicate textures, floating accompaniment.

Two years after Rachmaninoff’s death, the young Frank Sinatra crooned “Full Moon and Empty Arms,” in which songwriters Buddy Kaye and Ted Mossman recycled the finale’s sinuous main theme. The famous tune surfaces at least three times in the closing Allegro scherzando, more resplendent with each variation. The piano gets the final word, flouncing out with a bravura swoop as the concerto ends, emphatically and ecstatically.

Adapted from a note by René Spencer Saller © 2015

| First performance | November 9, 1901, Alexander Siloti, conducting with the composer as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | March 12, 1915, Max Zach conducting, with Ossip Gabrilowitsch as soloist |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 16, 2022, Hannu Lintu conducting with Kirill Gerstein as soloist |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 33 minutes |

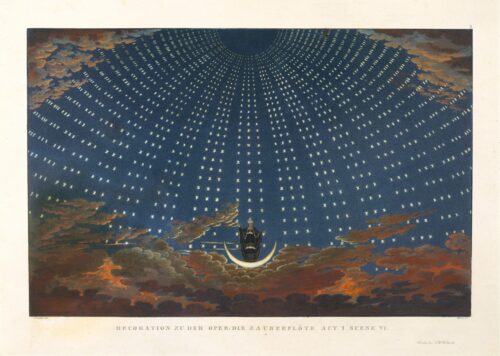

Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born 1840, Kamsko-Votkinsk, Russia

Died 1893, Saint Petersburg

Among the sketches found after Tchaikovsky’s death was a love duet—a scene from Romeo and Juliet in which Romeo sings the words “Oh tarry, night of ecstasy! Oh night of love, stretch thy dark veil over us!” to a musical phrase from the composer’s Romeo and Juliet fantasy overture. This duet is all that exists of a Romeo and Juliet opera that Tchaikovsky contemplated writing in 1878, after reading the play for the first time.

“Since I read Romeo and Juliet,” he wrote to his brother in a flush of enthusiasm, “Undine, Berthalda, Huldbrand [characters in his other operatic endeavors] seem to me the most childish nonsense. Of course I’ll compose Romeo and Juliet…It will be my most monumental work. It now seems to me absurd that I couldn’t see earlier that I was predestined, as it were, to set this drama to music.”

What might seem absurd to us is that Tchaikovsky had set the drama to music after a fashion, in his fantasy overture composed nearly ten years earlier, and that he had done so without reading or seeing the play!

The motivation if not the inspiration for the overture had been the composer and conductor Mily Balakirev. At 28, Tchaikovsky was young, and Balakirev’s influence was strong. He not only advised Tchaikovsky that he should adopt a Shakespearean subject for his next orchestral work, but provided him with a detailed narrative program and musical outline (going so far as to indicate what keys Tchaikovsky should adopt) and critiqued the work in progress. As a result, Balakirev’s presence can be felt in the structure of the music as well as in specific details.

In particular, Balakirev had objected to Tchaikovsky’s original introduction. He said it lacked beauty of power and that it needed to introduce the character of Friar Laurence with a chorale resembling Orthodox church music. In his reworking, Tchaikovsky created the now familiar introduction with its prayerful mood and an organ-like effect created by the woodwinds.

Tchaikovsky called his Romeo and Juliet music a “fantasy overture” but it’s really a symphonic poem, smelling as sweet as it would by any other name. The music adopts a conservative sonata form and does not follow a strict narrative—in this respect it’s quite different from a work like Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. Even so, the abstract form dovetails with the various elements of the play, the important characters and the overall dramatic arc.

After the revised slow introduction, Tchaikovsky presents the brawling feud of the Montagues and Capulets, fiery and tumultuous, and the ill-fated passion of Romeo and Juliet portrayed with muted and intertwining melodies. These are memorable even by Tchaikovsky’s standards: one for English horn and muted violas to an accompaniment of horns and bassoons; another for muted strings, suggesting, perhaps, the garden beneath the balcony at night. The traditional sonata-form “development” then amplifies the lovers’ music, “struggling” with the feuding music and Friar Laurence’s theme, and creating musical tensions to mirror those of the play. The furious climax may be the death of Tybalt at the hand of Romeo, but the love music dominates the ending, turning gradually to lament and tragic despair.

Yvonne Frindle © 2007/2025

| First performance | March 16, 1870, in Moscow, Nikolai Rubinstein conducting (first version); the work was completed in its final form in 1880 |

| First SLSO performance | November 17, 1911, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 22, 2017, David Robertson conducting |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 19 minutes |

Artists

Nikolai Lugansky

Nikolai Lugansky is renowned for his interpretations of Prokofiev, Chopin, Debussy, and especially Rachmaninoff. He has recorded all of Rachmaninoff’s works for piano and orchestra, and when he played the Second Piano Concerto with the

St. Petersburg Philharmonic in London, The Guardian declared “Rachmaninoff just doesn’t get any better than this.” In 2023, he celebrated the 150th anniversary of Rachmaninoff’s birth by performing all of his major solo piano works in concert cycles in Paris and London, as well as recitals in Vienna, Berlin, Brussels, Prague, and Amsterdam, and in the US he played Rachmaninoff concertos with the Cleveland Orchestra and at the Colorado Music Festival. He returns to the SLSO having most recently appeared in the 2016/17 season performing Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto.

He collaborates regularly with conductors of the caliber of Kent Nagano, Yuri Temirkanov, Manfred Honeck, Gianandrea Noseda, Stanislav Kochanovsky, Vasily Petrenko, and Lahav Shani, performing with leading international orchestras such as the Berlin Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra. He appears at some of the world’s major music festivals, including Aspen, Tanglewood, Ravinia, and Verbier, and his chamber music partners include violinists Vadim Repin and Leonidas Kavakos, and cellists Alexander Kniazev and Mischa Maisky.

This season’s highlights include concerts with the NHK Symphony Orchestra (Tokyo), NDR Radiophilharmonie (Hanover), Brussels Philharmonic, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Berlin Konzerthaus Orchester, Philharmonia Orchestra (London), and Orquestra Sinfônica do Estado de São Paulo. He continues touring his Wagner transcriptions, appearing at leading concert halls throughout Europe and in London, and gives recitals in Korea, Bogotá, and in Aspen, Kansas City, and Washington, DC. In July he will perform Beethoven with Stéphane Denève and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

His award-winning recordings include Rachmaninoff’s piano sonatas (which won the Diapason d’Or), concertos by Grieg and Prokofiev (Gramophone Editor’s Choice), César Franck’s Preludes, Fugues and Chorales (Diapason d’Or), and Rachmaninoff’s Études-Tableaux (Gramophone Editor’s Choice and Radio France’s Classica Choc de l’Année 2023). His 2024 recording, Richard Wagner: Famous Opera Scenes, won the Premio Abbiati del Disco for solo repertoire, and was included in the GramophoneBest Classical Albums of the Year.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.