Bernstein and Williams (March 21-22, 2025)

Program

March 21-22, 2025

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Yin Xiong, cello

Akiko Suwanai, violin

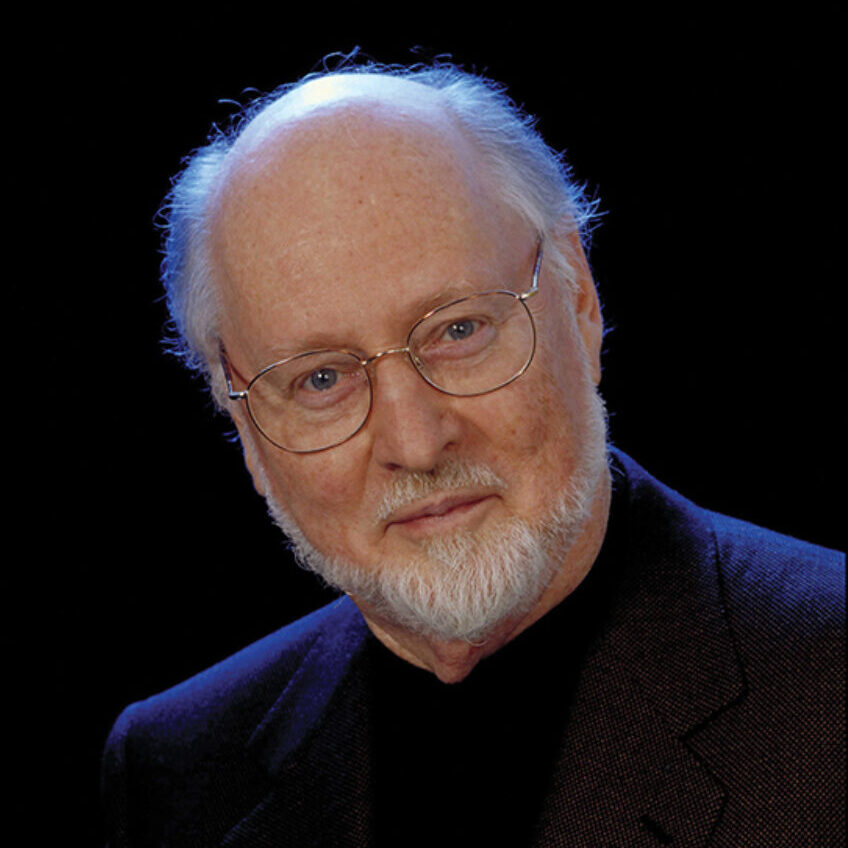

John Williams (b. 1932)

- Theme from Seven Years in Tibet

Guillaume Connesson (b. 1970)

- Les Horizons perdus (Lost Horizons) Violin Concerto

- Premier voyage

- Shangri-La 1 – Deuxième voyage

- Shangri-La 2

Akiko Suwanai, violin

US Premiere

Intermission

Adolphus Hailstork (b. 1941)

- An American Port of Call

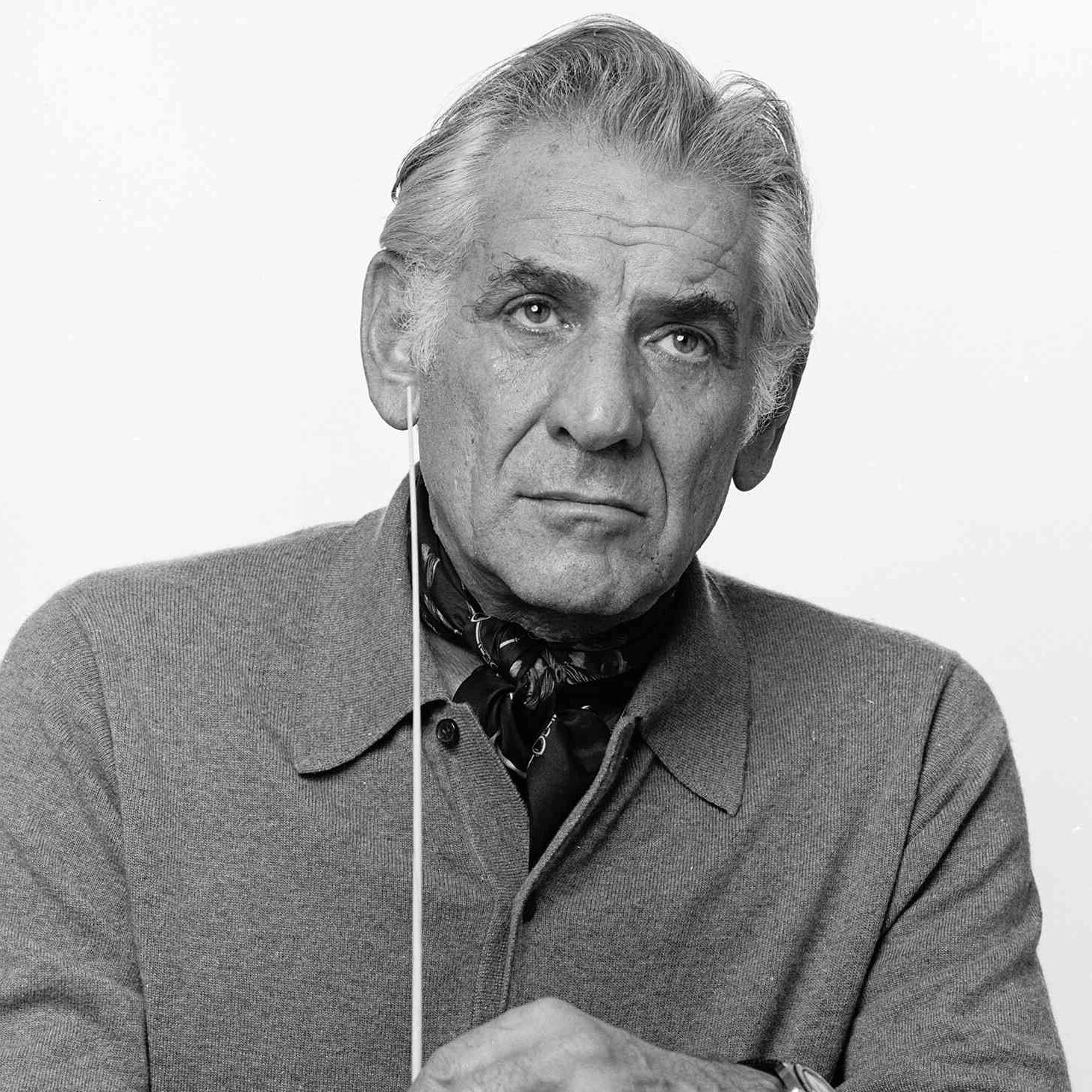

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990)

- Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront

- Andante (with dignity) – Presto barbaro —

- Adagio – Allegro molto agitato –

- Andanta largamente – More flowing – Lento –

- Moving forward, with warmth –

- Allegro non troppo, molto marcato –

- A tempo (Poco più sostenuto)

Cinematic Visions

For this concert, Stéphane Denève has thoughtfully blended the familiar and the rare with four works, each of which evokes spectacular visions and powerful emotions. These pieces can stand alone in their beauty and effectiveness, but in combination they display a marvelous synergy.

In the first half, the pieces by John Williams and French composer Guillaume Connesson find affinities in their Tibetan settings, the isolation of their protagonists, and the spiritual conflicts they embody. Both feature string soloists: SLSO cellist Yin Xiong in the Williams and guest violin soloist Akiko Suwanai in the Connesson. Strictly speaking, only Williams’s theme from Seven Years in Tibet comes from the cinema (Connesson’s Lost Horizons concerto was inspired by a novel), but both works convey the epic drama we associate with the big screen.

In the second half, we’ll hear a concert-hall classic that began life in the cinema—and on the cutting room floor. In part a musical salvage operation, Leonard Bernstein’s symphonic suite from On the Waterfront sidesteps the inherent challenges of composing for film (the need to be subservient to dialogue, for example, or the inevitable, ruthless cuts during editing). The result has a purely musical drama that’s independent of the original film and its story, although we recommend watching it—as Bernstein writes, it contains one of Marlon Brando’s greatest performances.

Both Bernstein and Adolphus Hailstork paint portraits of vibrant, bustling port cities. As William K. Zinsser wrote for its 1960 recording, On the Waterfront is a poem to New York, with its restless rhythms and searching melodies forming the “alternating current of New York life.” Meanwhile, Hailstork’s concert overture, An American Port of Call, completed in the 1980s, depicts the great port of his own hometown, Norfolk, Virginia. Again, there’s a bustling, jazzy energy juxtaposed with subtle tenderness and soaring lines.

Perhaps what connects all four works is the profound inner tensions as they balance energy and calm, violence and deeper longings—things for which words aren’t aways sufficient but music can speak volumes.

Theme from Seven Years in Tibet

John Williams

Born 1932, New York City

In the late 1970s, John Williams restored the preeminence of symphonic film music, which had declined with the growing popularity of rock and pop soundtracks in the 1960s. Working with directors Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, he played an essential role in the blending of New Hollywood auteurism with nostalgia for Golden Age cinema—resulting in the blockbusters Jaws, Star Wars, and Raiders of the Lost Ark. His music is poignant and varied, rooted in his background as a jazz pianist, built on an encyclopedic knowledge of classical techniques, and wrapped in the orchestrational styles of late Romanticism and modernism.

Apart from his work on tentpole franchises, Williams has scored a number of smaller dramas and historical epics. Seven Years in Tibet is a 1997 film by the French director Jean-Jacques Annaud. It tells the real-life story of the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer (played by Brad Pitt), who in 1944 escaped a British internment camp in India and trekked to Tibet, where he became a tutor to the young Dalai Lama, remaining there until the People’s Republic of China annexed the region in the early 1950s.

Shortly before the film’s release, a journalist discovered Harrer had joined the Nazi party in 1933 and enlisted in the SS in 1938. In response to the controversy, the elderly Harrer said he’d joined only to further his career as an alpinist under Hitler’s regime, and had committed no atrocities himself. The film’s director commented: “I had suspected for a long time that one of the hidden scars Heinrich Harrer had to heal was left by a possible connection with the Nazis when he left Austria in 1939. When he returned … he devoted his life to nonviolence, human rights and racial equality. The film, Seven Years in Tibet, revolves around guilt, remorse and redemption.”

Williams’s original soundtrack featured cellist Yo-Yo Ma as soloist. The theme is lush, with a sense of romance and adventure coursing through its melodies. A contrasting section evokes Tibet with scales and instrumental colors associated with Asian musical traditions. The score earned Williams both Golden Globe and Academy Award nominations.

Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | The film Seven Years in Tibet was released in 1997 with a soundtrack featuring cellist Yo-Yo Ma |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | solo cello; 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (one doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (one doubling E-flat clarinet), 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, 6 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, piano (doubling celesta), strings |

| Approximate duration | 7 minutes |

Lost Horizons Violin Concerto

Guillaume Connesson

Born 1970, Boulogne-Billancourt, France

The music of Guillaume Connesson is especially important to Stéphane Denève, who in recent seasons has conducted the SLSO in works such as the saxophone concerto A Kind of Trane, Flammenschrift and The Shining One, and the 2022 premiere of Astéria (Second Nocturne for Orchestra). “I adore his music because it continues the great tradition of French music,” Denève says. “It’s extremely richly orchestrated, very colorful … and it’s very accessible music of today.”

Connesson’s violin concerto Les Horizons perdus (Lost Horizons) was premiered in September 2018 by violinist Renaud Capuçon and the Brussels Philharmonic conducted by Denève.

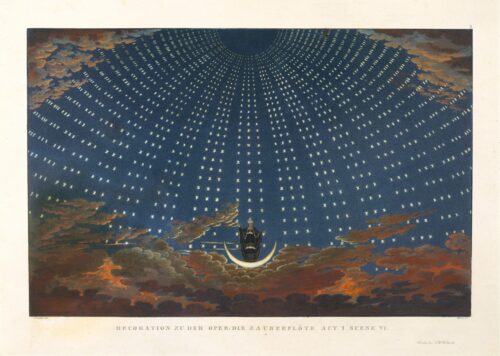

The title comes from the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by English author James Hilton—best remembered for coining the name “Shangri-La”—a city of earthly paradise. In the novel (and the 1937 Frank Capra film adaptation), a British diplomat survives an airplane crash in Tibet and takes refuge in a lamasery (a monastic Buddhist community) where time slows and people can achieve near immortality. He then faces the dilemma of returning to his life in London or staying in Shangri-La. Ultimately he departs, but seeks to return one day.

“It is this inner conflict and radical opposition between active life and the absolute of the inner life that constitute the fabric of this work,” Connesson writes. The first and third movements of the concerto (First Voyage and Second Voyage) reflect the fast and busy experience of the regular world, while the second and fourth movements (Shangri-La 1 and 2) are meditations set at the suspended pace of the utopian monastery.

After an “anxious” orchestral introduction, explains Connesson in his program note, the first movement (First Voyage) is built on three strongly contrasting themes: dramatic music for the whole orchestra; a relentless march; and a “passionate lyrical outburst.” These are combined in “a wild race to the abyss.”

The second movement (Shangri-La 1) is a short intermezzo depicting the travelers’ fascination with this strange place. Its hypnotic incantations lead to a short cadenza for the soloist that segues into the third movement. Second Voyage is an exuberant dance of joy, “intoxicated” with energy and rhythm.

The finale (Shangri-La 2) is a slow and lyrical movement whose tranquility is experienced as the culmination of the whole work. It’s no longer a portrayal of a place, as in Shangri-La 1, but a “plunge into the soul and its quest for the Absolute.” The end arrives with a new theme, writes Connesson, “as the solo violin, muted, sings as tenderly as can be of rediscovered ties with childhood.”

Unlike Hilton’s novel, which leaves it ambiguous whether one can ever return to Shangri-La, Connesson’s music is sure of it.

Adapted from a note by Benjamin Pesetsky © 2025

| First performance | September 14, 2018, Stéphane Denève conducting the Brussels Philharmonic Orchestra with Renaud Capuçon as soloist |

| First SLSO performance and US premiere | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | solo violin; 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, timpani, percussion, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 29 minutes |

An American Port of Call

Adolphus Hailstork

Born 1941, Rochester, New York

Raised in Albany, New York, Adolphus Hailstork was a boy soprano in the Episcopal Church and studied voice, piano, and organ. He completed a bachelor of music degree at Howard University in 1963, then went to France for the summer, where he studied at the American Conservatory, Fontainebleau, with the famed pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. His classical idols included Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein. In 1965, he enrolled at the Manhattan School of Music, where he studied with David Diamond and graduated with a master of music degree. After service in the US Army, he completed his education at Michigan State University, East Lansing, earning a doctorate.

Since the 1980s, Hailstork’s music has been commissioned and performed by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Los Angeles Philharmonic, among others. In January 2021, his Fanfare on Amazing Grace was played by “The President’s Own” US Marine Band as part of the prelude to the inauguration of President Joe Biden. He has also written a substantial body of vocal, keyboard, and chamber music, and is now Professor Emeritus of Music and Eminent Scholar at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.

Hailstork wrote An American Port of Call in 1984 for the Virginia Symphony Orchestra, which premiered it in 1985. In his program note, Hailstork writes:

The concert overture, in sonata-allegro form, captures the strident (and occasionally tender and even mysterious) energy of a busy American port city. The great port of Norfolk, Virginia, where I live, was the direct inspiration.

An American Port of Call opens with a sharp fanfare from which the syncopated main theme gradually emerges—finally heard clearly in the clarinet, marked “jazzy.” Twice, a bassoon solo bridges plaintively into slower, lusher sections, contrasting with the raucous energy rushing through the rest of the piece.

Benjamin Pesetsky, San Francisco Symphony © 2024

Used with permission.

| First performance | 1985, JoAnn Falletta conducting the Virginia Symphony Orchestra (the same artists recorded the work in 2011) |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 9 minutes |

Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront

Leonard Bernstein

Born 1918, Lawrence, Massachusetts

Died 1990, New York City

Bernstein in Hollywood

In 1954, when he was 36 years old, the composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein received a commission to score a new film by Elia Kazan, On the Waterfront, a gritty drama about star-crossed lovers and warring stevedores in postwar New York. After declining the offer, Bernstein, who had never before composed an original film score, saw a rough cut of the movie and changed his mind. He took a leave of absence from his teaching position at Brandeis University and spent three months in Hollywood, painstakingly crafting a symphonic structure, scene by scene, to bolster the film’s emotional trajectory.

Bernstein was not bedazzled by Tinseltown. “Hollywood is exactly as I expected it, only worse,” he wrote in a letter to Aaron Copland. He further described his dismay in his book The Joy of Music:

I thought [the film] a masterpiece of direction, and Marlon Brando seemed to me to give the greatest performance I had ever seen him give, which is saying a good deal. I was swept away by my enthusiasm into accepting the commission to write the score, although I had thereto resisted all such offers on the grounds that it is a musically unsatisfactory experience for a composer to write a score whose chief merit ought to be its unobtrusiveness.

Bernstein understood the constraints of the medium (“I had to keep reminding myself that it is really the least important part, that a spoken line covered by music is a line lost and not necessarily a loss to the picture”), but he still found the editing process demoralizing:

The composer sits by, protesting as he can, but ultimately accepting, be it with a heavy heart, the inevitable loss of a good part of his score. Everyone tries to comfort him. ‘You can always use it in a suite.’ Cold comfort.

Although the finished score was nominated for an Academy Award, Bernstein was so disillusioned by the experience that he never accepted another film commission. (The scores for the movies On the Town and West Side Story were adapted from the Broadway stage productions.)

The composer’s triumph

Bernstein took his comfort where he could, however, and the following year he reconfigured his score for On the Waterfront as a continuous 20-minute symphonic suite. Performed without pause, the musical sections, in Bernstein’s words, “follow as much as possible the chronological flow of the film itself.”

The suite is unified by the melancholy horn melody that opens the work and serves as a recurrent leitmotiv for the battered but unbowed hero, Terry (Brando’s character). The music is by turns tender and mournful, agitated and brutal. A ferocious, percussion-heavy Presto barbaro section in the first few minutes dramatizes the dehumanizing dock work and inevitable eruptions of violence. In a section marked More flowing (about seven minutes in), a delicate love theme sung by the flute over clarinets and harp evokes Terry’s lover, Edie (played by Eva Marie Saint). The scherzo-like Allegro non troppo, by turns frenetic and somber, is followed by a yearning recapitulation of the opening theme, a fitting conclusion to a classic tale of loss and redemption.

But even with no knowledge of the film or its story, Bernstein’s Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront stands on its own as an eloquent tribute to the American melting pot: a frantic, mercurial, sordid, and sublime pastiche of European classical conventions and American jazz.

René Spencer Saller © 2013

| First performance | The film On the Waterfront was released in 1954, opening in New York on July 28, and the score was nominated for an Academy Award; the symphonic suite was premiered on August 11, 1955, at the Tanglewood Festival, the composer conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra |

| First SLSO performance | October 7, 1988, Leonard Slatkin conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 18, 2015, conducted by Steven Jarvi |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, contrabassoon, alto saxophone, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, 2 timpani, percussion, harp, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 22 minutes |

Artists

Yin Xiong

Yin Xiong was appointed to the SLSO cello section by Music Director David Robertson at the start of the 2016/17 season. She has received numerous prestigious awards, including prizes at the Fourth International Tchaikovsky Competition for Young Musicians and the Fourth and Fifth National Cello Competitions of China. She also won the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (HKAPA) concerto competition for five consecutive years. She made her concerto debut with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra at age 17 under Edo de Waart, and has collaborated with János Fürst, François-Xavier Roth, and Alexander Shelley.

A dedicated chamber and orchestral musician, she was deeply influenced by her parents, both professional cellists. As a member of the Academy String Quartet, she represented HKAPA in performances throughout Asia and Europe. She also performed with the Hong Kong-based ensemble Cellistra, presenting concerts and community engagement programs across Asia. As the founding cellist of the Hsin Trio, she premiered Toshio Hosokawa’s Piano Trio in the United States, was featured in Juilliard Open Studio, and performed in the US and in China.

Her orchestral career began at age 20 with the Hong Kong Sinfonietta while also performing regularly with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. She served as principal cellist of the HKAPA Orchestra and the Oberlin Orchestra and was co-principal of the Juilliard Orchestra. As principal cellist of the Pacific Music Festival from 2006 to 2009, she worked with conductors Valery Gergiev, Riccardo Muti, Christoph Eschenbach, and Michael

Tilson Thomas.

A passionate educator, she has served on the faculty of HKAPA and the Macau Youth Orchestra, and was a teaching assistant to Darrett Adkins at Oberlin Conservatory.

Born in Shanghai, Yin Xiong studied at the Shanghai Conservatory and attended HKAPA on full scholarship, studying with Ray Wang. She holds a Professional Diploma with Distinction from HKAPA, an Artist Diploma from Oberlin, and earned accelerated bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Juilliard, studying with Darrett Adkins and Joel Krosnick. She also enjoys playing baroque cello and viola da gamba.

Akiko Suwanai

Since winning the International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1990, Japanese violinist Akiko Suwanai has enjoyed a flourishing career, performing chamber music internationally and appearing with orchestras and conductors at the highest level. She returns to the SLSO following performances of Bruch’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in the 2021/22 season finale.

This season began with a return to the National Symphony Orchestra Taiwan, again playing Bruch, which she will reprise with the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne and Sakari Oramo on tour in Japan. In other highlights, she joins NHK Symphony Orchestra and Fabio Luisi on tour in both Asia and Europe, performing Berg’s Violin Concerto, and she plays Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 5 with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

She is known for her breadth of repertoire—acclaimed for performances

of core violin works and equally recognized for her interpretations of lesser performed works and her passion for new music. This season, for example, she performs recent works such as Toshio Hosokawa’s Genesis (Gürzenich Orchestra) and Connesson’s Horizons perdus as well as Dvořák’s Violin Concerto (Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen with Paavo Järvi and the Singapore Symphony Orchestra with Kahchun Wong). Similarly, her recordings range from Brahms: The Sonatas for Violin and Piano (2024) and Bach’s Complete Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (2022) to music by Tōru Takemitsu with the NHK Symphony Orchestra (Paavo Järvi). She has also recorded and given premieres of Peter Eötvös’ Seven at the Lucerne Festival (Pierre Boulez) and the BBC Proms (Susanna Mälkki), and given the Asian premieres of violin concertos by James MacMillan, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Krzysztof Penderecki, and other important works of our time.

In 2012, she launched the Tokyo-based International Music Festival NIPPON as Artistic Director. This bi-annual festival presents a variety of guest orchestras and chamber concerts and commissions new works, including Karol Beffa’s Violin Concerto with the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen and Dai Fujikura’s Pitter-Patter with pianist Boris Berezovsky.

Akiko Suwanai plays the Charles Reade Guarneri del Gesu violin, generously loaned to her by the Japanese-American collector and philanthropist

Dr. Ryuji Ueno.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.