Debussy and Liszt (March 28 & 30, 2025)

Program

March 28 & 30, 2025

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Michael Spyres, tenor

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

- Prélude à l’aprés-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun)

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

- Les Illuminations, Op. 18

- Fanfare –

- Villes

- Phrase – Antique

- Royauté

- Marine

- Interlude –

- Being Beauteous –

- Parade

- Départ

Michael Spyres, tenor

Intermission

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

- Lieder eines fahrender Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer)

- Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht (On my sweetheart’s wedding day)

- Ging heut’ Morgen übers Feld (I went out this morning into the fields)

- Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer (I have a red-hot knife)

- Die zwie blauen Augen (The two blue eyes)

Michael Spyres, tenor

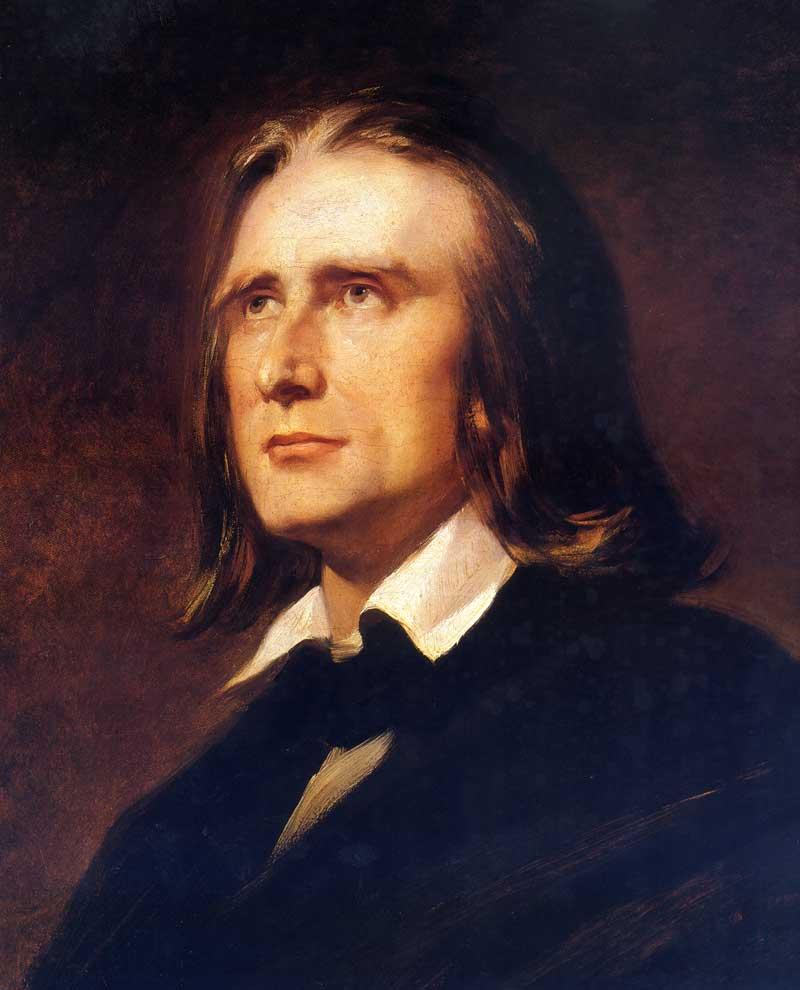

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

- Les Préludes

Lyrcial Daydreams

In modern orchestral concerts, singers—and words—are the exception rather than the rule. Most weeks, we revel in pure instrumental sound, even when there’s a literary inspiration in the background. For this concert of “lyrical daydreams,” however, Stéphane Denève has united music, words, and the human voice, and each work, even the two for orchestra alone, has poetry at its heart.

In the first half of the concert, French Symbolist poets of the late 19th century, Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud, lead us into a world of dreams and visions, and the “derangement of the senses.” Mallarmé’s L’Après-midi d’un faune, with its blurred images of nymphs “drowsy with tangled slumbers,” finds its aural counterpart in Claude Debussy’s washes and dabs of color, “vague” harmonies, and the undermining of musical pulse. Focusing on atmosphere rather than narrative, the groundbreaking Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun ushered in the 20th century, in 1894.

In 1938, the young Benjamin Britten was introduced to Rimbaud’s poetry. Enraptured by its kaleidoscope of dreamlike images, he set about writing Les Illuminations, the first work in this concert to feature our tenor soloist Michael Spyres. In his introduction to the vocal score, the writer Edward Sackville-West pointed out that “it is always a picture, not an idea, that is evoked.” With modest forces—voice and strings—Britten created a work of astonishing finesse, full of brilliant color and vivid images.

After intermission, the inspiration is confessional poetry by the composer himself, Gustav Mahler. Songs of a Wayfarer is another youthful work (like Britten, Mahler was in his mid-20s), and it speaks with almost naïve directness of the torments of disappointed love. We’ve all been there, but few have turned the experience into music of such emotional power.

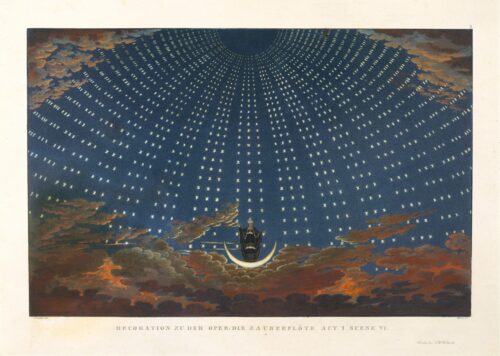

With Les Préludes we return to symphonic sound and the world of 19th-century French poetry. In this case, however, Franz Liszt’s inspiration as retrospective: he turned to the Méditations poétiques of Alphonse de Lamartine only after writing his symphonic poem. But the result is a perfect demonstration of the synergy that emerges when poetry, vision, and music unite.

Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun

Claude Debussy

Born 1862, Saint Germain en Laye, near Paris

Died 1918, Paris, France

Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune is, in a poetic way, concerned with qualities of both light and time. It paints a dreamscape in which sprites emerge from shadows and disappear back into them, a realm in which events unfold in the incalculable time of dreams.

Completed in 1894, this work was inspired by the poem L’après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun) by the Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. The poem was notorious as much for its languid eroticism as for its allusive, at times obscure, imagery. Mallarmé describes what may or may not be the daydreams of a young faun—a mythical creature, half man and half goat. On a warm afternoon, this faun encounters—or perhaps only imagines—woodland nymphs, whom he caresses and kisses but cannot possess, for they always slip away from him.

Mallarmé’s poem abounds with musical references, most notably that of the faun playing upon a reed flute. Debussy evokes this activity in the opening measures. But more than transforming a poetic image into a musical one, the celebrated flute solo that begins the work establishes a sense of musical ambiguity that permeates the entire composition and closely parallels the allusiveness of Mallarmé’s verses. Just as the poet maintains uncertainty about the reality of his faun’s experiences, the flute melody subtly undermines conventional harmonic principles. Debussy maintains this procedure throughout his Prelude, whose chords rarely form or resolve in a manner that leaves us sure where the music has arrived, or where it is going next.

Suggestive though Debussy’s music is, it offers nothing like a line-by-line representation of Mallarmé’s text. Instead, it conveys the general character and atmosphere of L’après-midi d’un faune. This approach seems fitting for a musician with whom the term “Impressionism” has been associated, and it is perhaps the only one suited to the verses that inspired the work, in view of the deliberate uncertainties of the poem’s narrative. Mallarmé himself was pleased with how the music “draws out the emotion of my poem,” as he told Debussy, though the novel qualities of the music surprised him.

That novelty—the originality of Debussy’s melodic and harmonic ideas, as well as of his orchestration—is difficult to appreciate today, so familiar has his style become. The work is now recognized as one of the prophetic compositions of the fin de siècle period, its ethereal opening signaling the birth of modern music.

Composer and conductor Pierre Boulez, who has made his own musical settings of Mallarmé’s poetry, articulated this view when he wrote that “the flute of the faun brought new breath to the art of music.”

Paul Schiavo © 2008

| First performance | December 22, 1894, in Paris, Gustave Doret conducting the orchestra of the Société National de Musique |

| First SLSO performance | January 30, 1908, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | February 8, 2015, Stéphane Denève conducting |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, percussion, 2 harps, strings |

| Approximate duration | 11 minutes |

Les Illuminations

Benjamin Britten

Born 1913, Lowestoft, England

Died 1976, Aldeburgh, England

When the hallucinatory world of certain poetry is coupled with the right music, its strange visions can become all the more vivid. Such is the case with Les Illuminations, Benjamin Britten’s setting of verses by the French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud.

Rimbaud might seem an unlikely source of interest for a British composer. Proud of their country’s rich literary heritage, English musicians have usually turned to English verse for their songs and song cycles. Britten, the foremost English composer of the 20th century, was no exception. His substantial output of vocal music includes settings of English poets ranging from John Donne to his friend W.H. Auden. But in 1938, Auden introduced him to Rimbaud’s poetry. It resonated, and by March 1939 he’d begun work on Less Illuminations. The cycle was completed seven months later in the United States, where for three years Britten maintained a self-imposed exile, discouraged by what he felt to be a deepening political, social, and artistic conservatism in his homeland.

The scoring for soprano and string orchestra reflected a promise Britten had made to Swiss soprano Sophie Wyss, and it was she who gave the first performance in 1940. Soon after, he began performing the cycle with his partner Peter Pears as soloist, and thus the work entered the repertoire of tenors.

The work draws its text, and its title, from a series of poems Rimbaud wrote in the early 1870s, during the brief few years of his literary career. (The poet, who worked and lived with a fierce intensity, produced his entire literary output before turning 20.) Rimbaud dedicated the series to Paul Verlaine, who explains that the title—which might be translated as “lights” in the sense of festive, artificial lighting—came from English rather than French, and that the “illuminations” in question are those of Medieval scribes: intricately illustrated miniatures, gleaming with gold leaf, vermilion red, and ultramarine blue. Typical of Rimbaud—a poet who cultivated the “derangement of all the senses”—the verses present weird, surreal images and evocative but often obscure allusions. Britten’s music helpfully ushers us into their strange world.

The song cycle is built around the recurring image of a parade—a mad parade, “a savage parade,” as the introductory “Fanfare” puts it. “Villes,” the second song, establishes a small-town atmosphere whose familiarity is undermined by surreal happenings, just as in the music Britten undermines the sound of familiar harmonies with unusual chord changes and slithering chromatic runs. “Phrase” heightens the sense of an otherworldly ambience through the use of harmonics—high-pitched, ethereal tones—in the violins. The dance announced in its final line follows in “Antique.”

Further visions are conveyed in “Royauté,” “Marine,” and “Being Beauteous.” In setting these poems, Britten employs a wide range of string sonorities to capture their varied moods. “Interlude” is a mostly instrumental episode, concluding with a reprise of the cycle’s opening declaration, the words now set to what seems haunted, wistful music. With “Parade,” we reach the climax of the cycle, as swirling sonorities and crazed march figures suggest something of the disturbing procession the verses describe. “Départ” now provides a denouement, as poet and composer quietly take leave of the strange psychic landscape they have visited.

Adapted from notes by Paul Schiavo © 2014 and Yvonne Frindle

| First performance | January 30, 1940, in London with the Boyd Neel String Orchestra and soprano Sophie Wyss |

| First SLSO performance | February, 18, 1962, Leigh Gerdine conducting, with tenor Leslie Chabay |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 11, 2014, David Robertson conducting, with tenor Nicholas Phan |

| Instrumentation | high voice; strings |

| Approximate duration | 23 minutes |

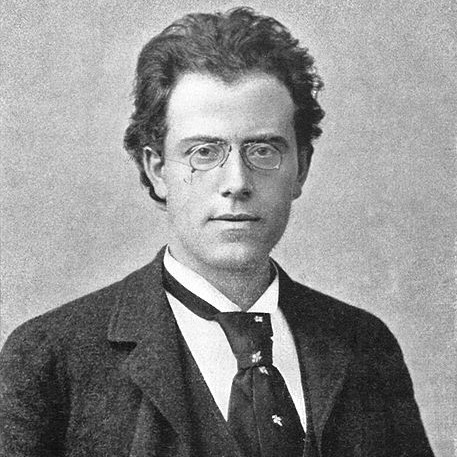

Songs of a Wayfarer

Gustav Mahler

Born 1860, Kalište, Bohemia

Died 1911, Vienna, Austria

When did you last use the word “wayfarer” in conversation? The word is a quaint way of referring to a traveler, and since it specifically refers to a traveler on foot, it’s hardly surprising it has dropped from common usage. But for Gustav Mahler, writing at the end of the 19th century, “fahrenden Gesellen” held rich connotations. The title of his first fully mature work refers to the itinerant or wandering journeyman. The protagonist is a man beyond apprenticeship but not yet a member of the guild; beyond the rule of parents and master but not yet constrained by professional or family obligations. Today’s “wayfarer” could be the young graduate spending a year jobbing around the world before entering the rigors of the workforce.

Such experiences offer a chance for personal growth and often enforced maturity; Mahler clearly saw the journey as one for nostalgic and somber reflection. He was himself only 25 when this set of four songs was completed, and he wrote his own texts, attempting to disguise the autobiographical elements in a stylistic imitation of German folk poetry. He was reluctant to admit to their authorship, fearing they might be thought naïve and sensitive to the personal suffering the texts revealed:

I’ve written a cycle of songs [texts], numbering six at present, which are all dedicated to her. She has not seen them. What more can they tell her than what she already knows? I’m going to enclose the first song too, although the meagre words cannot express even a small part. The songs tell the story of a journeyman whom Fate has dealt a blow, and who goes out to roam through the world.

For Mahler, the “blow” was an unhappy love affair with Johanna Richter, a blue-eyed soprano at the theater in Kassel, where Mahler was deputy Kapellmeister, in charge of the chorus. Mahler eventually moved to Prague in August 1885, but his disappointment lived on in Songs of a Wayfarer.

The romantic scenario is strikingly like that of Franz Schubert’s Winterreise (The Winter Journey), composed in 1827, and both song cycles close with imagery of the linden tree, the tree of lovers in German folklore. In his music, Mahler, like Schubert, contrasts his delight in the beauty around him with torment of spirit—clothing folklike melodies in delicate orchestrations while taking the music through a complex harmonic journey in which no song ends in the key it begins.

The first song witnesses the marriage of the beloved to another. Clarinets and harp establish the mournful motif of the opening, with its unsettling pulse. Through intimate use of his orchestral palette and clever handling of small musical motifs, Mahler avoids extreme pathos. Even so, through the mask of village celebration, we sense that all is not well.

On my sweetheart’s wedding day all will be merry … I alone shall be sad. Flowers and birds, sing and bloom no more … Spring has gone; never shall I sing again.

The melody of the second song evolves from a single descending interval in the first. (The same idea motivates the first movement of Mahler’s First Symphony.) This song is jaunty, with a clearly established, although wandering, major tonality.

In the fields the finch sang good-morning to me … How I like this happy world! The blue bells swing and ring, the world is fresh, the world begins to sparkle in the sunshine. Shall I be happy too? Ah, no! My longing shall never be stilled.

The third song is marked “schnell und wild” (fast and wild) and the effect is stark, brutal, and desperate. Repeated cries—“woe is me!”—punctuate the song. Relief is found in a contrasting interlude: a tender comparison of the beloved’s eyes with the blue of heaven.

There is a red-hot knife which stabs my breast. Oh pain! Oh grief! It cuts so deep … why must I carry this evil guest? When the sky is blue, I see two blue eyes; when I go in the golden fields I see her golden hair under summer skies. When I start to dream at night I wake hearing her laughter. … I wish I could lie down and die and never open my eyes again.

The cycle concludes with a world-weary funeral march featuring the striking color of three flutes playing low in their register, English Horn (supreme among mournful instruments), and harp. The gentle vocal line slowly yields to the gloomy atmosphere. As with the second song, this material was to turn up in the First Symphony.

My darling’s sweet blue eyes have sent me into the wide world and I must leave the place that was so dear to my heart. Why did you ever look at me? Now my heart is full of anguish. I have gone out into the night, and no one said farewell. A linden-tree by the roadside gave me shade for sleep, and snowed its blossoms over me. I forgot how life can hurt and all was well again … love and pain and world and dream.

Yvonne Frindle © 2019

| First performance | March 16, 1896, with soloist Anton Sistermans and the composer conducting the Berlin Philharmonic |

| First SLSO performance | February 3, 1951, Vladimir Golschmann conducting, with contralto Elena Nikolaidi |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 24, 1978, Leonard Slatkin conducting, with mezzo-soprano Claudine Carlson |

| Instrumentation | medium voice; 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (one doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (one doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 18 minutes |

Les Préludes

Franz Liszt

Born 1811, Raiding, Hungary

Died 1886, Bayreuth, Bavaria

Franz Liszt made his reputation as a virtuoso pianist, dazzling audiences across Europe, and his earliest compositions were showpieces for his instrument. But he was not content to be only a composer for the keyboard, as his friend Frédéric Chopin had been. In 1848, Liszt ended his career as a touring concert pianist and devoted himself to mastering orchestral composition. In the process he invented a new musical genre, the symphonic poem (or tone poem), a single-movement work intended to express a literary or dramatic “program” or other extra-musical idea.

Les Préludes, the third and most popular of Liszt’s symphonic poems, underwent a particularly long and complex genesis. It first took form in 1849 as an overture to a choral work, The Four Elements. Three years later, he rewrote the music, divorcing it from the choral piece that had provided its themes, and renamed it “Symphonic Meditations.” Sometime before 1855 he again revised the work, its new title “Les Préludes” referring not to musical preludes but rather taken from the Méditations Poétiques by 19th-century French writer Alphonse de Lamartine.

Despite the music’s supposed debt to Lamartine, Liszt prefaced the score with his own explanation of its program, which is nothing less than the panorama of human existence itself:

What is our life but a series of preludes to that unknown Hymn the first and solemn note of which is intoned by Death?—Love is the enchanted dawn of existence; but what fate is there whose delights are not interrupted by some storm…? And what wounded soul, fleeing such tempest, does not seek solace in nature? But man does not long resign himself to the comfort of Nature’s bosom, and when “the trumpet sounds the alarm” [the only phrase to survive from Lamartine] he takes up his perilous post…

Some analysts have mapped the preface to the music, identifying the opening (Andante) as representing Spring and the quest for love, and the following Allegro ma non troppo as the life’s stormy tempests. An Allegretto pastorale then provides the calming consolations of Nature, with the final Allegro marziale animato representing battle and victory.

As he usually did with his tone poems, Liszt based Les Préludes on a single principal theme that recurs in various transformations throughout the work, lending a sense of continuity to the diverse episodes that comprise the score. This theme is introduced by the strings in the atmospheric opening measures and runs throughout the vigorous passages that follow. It also may be heard in the amorous and pastoral interludes in the middle of the work. Finally it emerges as a stirring march to close the composition.

Adapted from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2009

| First performance | February 23, 1854, in Weimar, conducted by the composer |

| First SLSO performance | November 10, 1911, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | November 11, 2014, Hannu Lintu conducting |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, strings |

| Approximate duration | 17 minutes |

Artists

Michael Spyres

Michael Spyres returns to the SLSO following his acclaimed debut appearance singing the title role in Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust in May 2023. Born and raised in a musical family in the Ozarks, and an alumnus of Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, he has appeared in the world’s most prestigious international opera houses, festivals, and concert halls, working with renowned conductors. His repertoire ranges from Baroque and Classical to the 20th century, but he is especially acclaimed for his work within the bel canto, Romantic, and French grand opera genres.

More recently he has emerged as a much-requested tenor in the German Helden (heroic) repertoire. Last year he made his Wagner debut as Lohengrin at Opéra du Rhin, as well as his Bayreuth Festival debut singing Siegmund in Die Walküre. He returns to Bayreuth in July to reprise Siegmund and make his role debut as Stolzing in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

Other performances of the 2024/25 season include Florestan in Fidelio (Vienna State Opera), Bacchus in Ariadne auf Naxos, the title role in Palestrina, and his role debut as Manrico (Il trovatore) for Houston Grand Opera. His concert engagements include Berlioz’s Nuits d’été (Luxembourg Philharmonic) and a European tour of Handel’s Jephtha with Il pomo d’oro, as well as solo concerts in London, Essen, and Lisbon.

In a rare combination, he is an impresario as well as a performer, and as Artistic Director of the Ozarks Lyric Opera since 2015, he has been involved in every aspect of the renaissance of his hometown opera company, producing 15 operas and five gala concerts. He has more than 40 audio and video recordings to his name, and is also active as a teacher and mentor of young artists and as a translator.

Michael Spyres’s accolades include the 2024 International Opera, Opus Klassik, and Oper! awards, as well as the 2022 Gramophone Classical Music Award, and in 2021, he was named a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters) by the French government.

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.