Peer Gynt (May 3-4, 2025)

Program

May 3-4, 2025

Stéphane Denève, conductor

Bill Barclay, writer and director

Camilla Tilling, soprano | Solveig

Vidar Skrede, Hardanger fiddle

St. Louis Symphony Chorus | Erin Freeman, director

Actors from Concert Theatre Works:

Caleb Mayo | Peer Gynt

Bobbie Steinbach | Åse

Robert Walsh | The Button Moulder

Kortney Adams | Ingrid, Anitra, Ensemble

Daniel Berger-Jones | Aslak, Begriffenfeldt, Ensemble

Caroline Lawton | The Woman in Green, Ensemble

Risher Reddick | The Dovre King (Mountain King), Mads Moen, Ensemble

Will Lyman | Voice of the Bøyg

Production

Cristina Todesco | Scenic Designer

Charles Schoonmaker | Costume and Puppet Designer

Maura Gahan | Puppet Co-Designer and Puppet Realization

Rachel Padula-Shufelt | Assistant Costume Deisgner

Stephanie Macklin | Costume Construction

Nicole Pierce | Dance Choreography

David Reiffel | Sound Designer

Brian Schott | Lighting Designer

Ron Bolte | Sound Engineer

Justin Seward and Cristina Todesco | Properties

Diane Healy | Stage Manager

Justin Seward | Production Manager

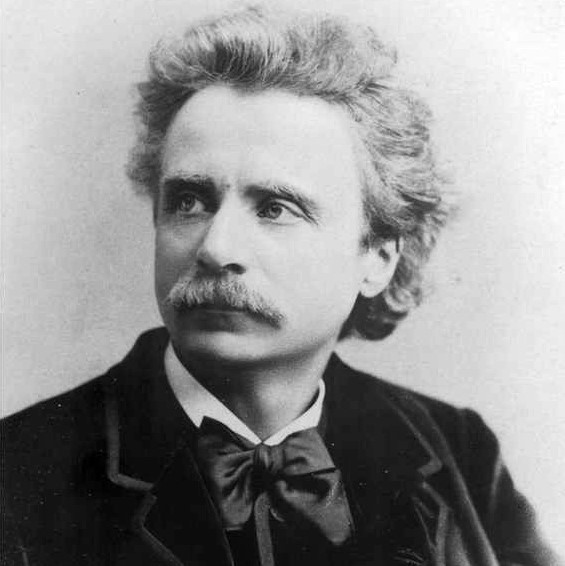

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

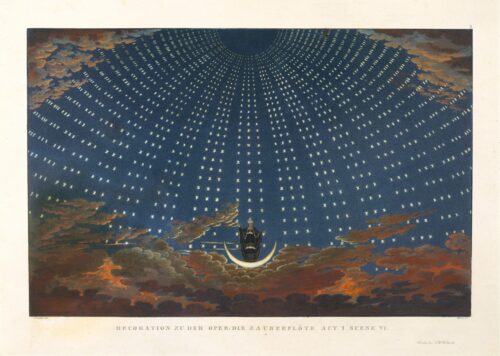

- Peer Gynt, Incidental music for the play by Henrik Ibsen

A new full-length adaption from the play by Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) for the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra. Originally commissioned by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Director’s Note

Henrik Ibsen’s sprawling verse play has always been intimidating to stage.

His protagonist encounters a who’s who of Scandinavian folklore across three continents, 40 scenes, and 60 years. As a contrast, Grieg’s original incidental score survives neatly in two concert suites, fashioned by the composer after the 1876 Oslo premiere. This new adaptation tries to tame the story while going back to the wilder incidental score, mining for fresh bits of Grieg you’ve probably not heard before.

It’s hard to identify a more exuberant writer than Ibsen in 1867. In its grab bag of genres from fantasy to naturalism, Peer Gynt is said to anticipate the literary modernism of the First World War. I rather think it anticipates film, cutting from place to place, exploring fantastical imagery, and using comedy to connect us to Peer the person (who many believed had actually lived). Those innovations still amaze readers today, and all this before he wrote his greatest plays: Hedda Gabler, A Doll’s House, Ghosts, The Wild Duck, and The Master Builder.

Like the play that barely contains him, Peer has a foot in both Romantic and Modernist impulses. A dreamer and an opportunist, he pursues the world’s temptations in the mold of the self-made man, only to realize at death’s door the hollowing consequences of individualism. In all the translations I’ve read, the word Self reigns supreme in Peer Gynt. His simple aim is to be who he is above all else. After all, didn’t Shakespeare counsel us to be true to thyself “above all”? Peer dares us to criticize him for this. What is amazingly insightful is in the decades since Ibsen wrote Peer Gynt, our global industrialized economy has only increasingly spun on this idea, as does our social media, celebritizing the Self one Instagram photo at a time. But where does compassion factor in? Where meaning? Is pleasure all? Peer’s cautionary tale of hedonism becomes more relevant with each passing day.

It is a joy to bring theatrical tools so fully into the concert hall with this iconic score. Too often, Peer Gynt is only known to us through Grieg’s greatest hits.

I have labored to find homes for as many unfamiliar movements from the original score as I could. To serve the music, the text had to be written from scratch, economizing the narrative while retaining the spirit of Ibsen’s many different meters and rhyming schemes. We have committed to a rare fully staged presentation in the concert hall so that Grieg’s iconic music can reunite with the grandeur of the story and the caprice of its characters. Above all, we have stayed true to the spirit of equal partnership between Ibsen and Grieg in our “concert-theatre” approach. I hope we are honoring these legends most however, in making something that feels true to us too.

Bill Barclay, Writer and Director

Synopsis

After an introduction by the Button Moulder, Peer Gynt arrives home after some time away and teases his mother, Åse, with stories before heading off to the wedding of a former sweetheart. There he first meets Solveig (who will become significant later). Peer gets drunk and abducts the bride, Ingrid. She quickly gets used to the idea, but Peer thinks better of it. Having escaped, Peer goes off to where he thinks he can’t be found, ending up in the realm of the Mountain King.

Peer meets the Mountain King’s daughter, the Woman in Green, and engages in some hanky-panky which, to his considerable surprise, necessitates marriage. So Peer flees again, but is quickly caught by trolls, who seem to be trying to steal his soul—but the prayers of the women at home, Åse and Solveig, are too powerful. The trolls make him question his own identity and actions, however.

After the struggle, Peer wakes up suddenly back in his own world, and contemplatively climbs a mountain to observe daybreak. He returns home, where his mother, Åse, grown very old in the meantime, doesn’t recognize him. After a short, confused conversation, she dies. Solveig appears, but Peer is not yet ready to accept her. In Solveig’s song, which follows this scene, she sings of the passing of time and her willingness to wait for Peer to come to her.

Continuing to ramble, Peer becomes wealthy gambling in South Carolina before returning to Europe as a magnate. A storm wrecks his yacht and he wakes up in North Africa, having lost his worldly possessions but none of his self-actualization. The people mistake Peer for a prophet—and perhaps they’re right. Welcomed by the Bedouin chieftain’s daughter, Anitra, his inevitable instinct is to seduce her, but he is unsuccessful. Peer decides to travel further, arriving in Egypt, where, standing before the Sphinx, he ends up in conversation with the keeper of the local madhouse. More self-examination.

Finally the Button Moulder, possibly an emissary from God, answers Peer Gynt’s forlorn call to his mother, Åse. He leads Peer to the hut where Solveig, now blind, accepts him with a closing lullaby.

© Robert Kirzinger, Published by kind permission of the author and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc.

Peer Gynt

Edvard Grieg

Born 1843, Bergen, Norway

Died 1907, Bergen, Norway

“To be, or not to be…” Even those who’ve never seen a production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet know how this line goes on. But what about this line:

“Peer, you’re lying!” You likely don’t recognize it. For Norwegians, however, when these words are quoted in conversation everyone knows how they go on. After Peer’s mother, Åse [aw-suh], accuses him of lying, he says “No, I am not!” He then refuses to swear that what he’s been saying is true, and Åse responds: “See, you dare not! It’s a lie from first to last!”

This is how Henrik Ibsen begins his five-act verse-play Peer Gynt [peah gint]. Even before we hear the first of Peer’s tall tales, it’s clear he’s a born liar, not to be trusted. He’ll even lie to his mother—completely without shame.

Americans don’t know much about Peer Gynt, or Ibsen’s play, which is rarely produced here. On the other hand, everyone knows at least some of Grieg’s Peer Gynt music, whether it’s from the concert hall, jazz (Duke Ellington), TV advertisements, heavy metal covers (Apocalyptica), or the movies (the Henley Regatta scene in The Social Network). But perhaps the true test of classical music fame is when your tune turns up in the Mac operating system. Type “We are nasty little trolls” and ask your Mac to read it with “Cellos” voice—of all the melodies Apple could have chosen, they settled on The Hall of the Mountain King.

Almost without fail, when we hear Peer Gynt in the concert hall it’s in one of two orchestral suites. Of the 80 or so minutes of music Grieg wrote for the theater, we’re familiar with maybe 30. Furthermore, those suites are out of context and out of dramatic order.

This show is a chance to experience the spirit of Ibsen’s play woven together with Grieg’s music. It’s a chance to hear Grieg’s music in its dramatic context. And through the choices Bill Barclay has made, it’s a chance to hear some of the rare jewels from the Peer Gynt music, not just the greatest hits.

One of those hits is Morning Mood, and one of the most popular misconceptions is that this theme has something to do with Norwegian fjords. It’s rare to come across a program note that doesn’t gleefully point out that Grieg wrote this music to accompany sunrise over the Sahara. In this show, you’re in a position to notice something more. There’s a reason Morning Mood sounds “Norwegian” to our ears. First, the scale it uses is more typical of Norwegian folk music than anything you’d hear in Morocco. More important, this theme is anticipated earlier in the play, in a scene that does take place in Norway, when Peer Gynt flirts with the Woman in Green, who turns out to be the daughter of the Mountain King. This throws a different light on things, suggesting that wherever Peer goes in his travels, he takes his essential Norwegian-ness with him and Morning Mood was Grieg’s way of showing that.

Morning Mood also reveals something important about the creative relationship between Grieg and Ibsen, because it’s not what Ibsen asked for. The playwright’s scene placed Peer on a beach in Morocco. At this point (Act IV) he’s a prosperous, middle-aged gentleman entertaining some dubious international friends: Mr. Cotton, Monsieur Ballon, Herr von Eberkopf, and Herr Trumpeterstrale (an American, a Frenchman, a German, and a Swede). Ibsen suggested Grieg devise music that would blend the national melodies of these friends, maybe even a “great musical tone-painting, to depict Peer Gynt’s wanderings.”

For whatever reason, Grieg didn’t do that, and Ibsen had made it clear that his suggestions were only ever that: suggestions. Which is just as well, since Grieg also ignored him in the crucial scene in Act III where Peer’s mother dies. In this scene, Peer returns home to find his dying mother in bed. They’re reminded of a game from his boyhood, when they’d pretend the bed was a sleigh, and the cat on the chair was a horse. Only now their roles are reversed, and Peer promises to drive his mother to the magical castle, to the gates of Paradise. “Gee-up!” he yells, and there follows an imaginary journey with jingling sleigh bells, the rushing wind, and trotting horses.

Ibsen had suggested the music might mirror Peer’s fantasy—the jingling bells and so on—but Grieg went in another direction. His somber, mournful music for The Death of Åse is in complete conflict with the image Peer is painting for his mother, which makes it all the more poignant. In this music you can hear just how out of touch with reality Peer really is; you can hear the sad irony of the scene. It’s not just about the death of an old woman, it’s about the loss of childhood fantasy.

The Death of Åse is noteworthy for another reason. Grieg composed it as “melodrama”, which in 18th- and 19th-century theater was a technical term referring to music that has been precisely written to underscore the dialogue.

(The words from the script are included in the music.) It’s a technique almost never heard in the concert hall today—although Mendelssohn included melodramas in his incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream—and you rarely hear it in the theater, but you might hear something like it in film soundtracks.

The melodrama technique is intended to heighten the effect of the words, to enhance the emotion, the drama, and sometimes the comedy of the scene. The Hall of the Mountain King is a good example. Today it’s familiar as purely orchestral music, but in Grieg’s conception, the music was tightly integrated with the scene, incorporating dialogue and singing from a chorus of increasingly excited trolls.

Grieg included other music for voices—a hymn for the chorus, songs for Solveig—as well as interludes and dances. Not only do all these numbers reveal Grieg’s great lyric and dramatic gifts, they also show his deep instinct for folk music, and his concern for naturalism and authenticity. For example, he included the distinctive sound of the Hardanger fiddle in the wedding scene, saying the music should be “played in perfect accord with dance traditions”—traditions he’d studied and knew well.

There was more earthy authenticity in Ibsen’s scene with the herd girls, and in this instance, Grieg provided exactly what Ibsen requested. Ibsen had told him that the scene could be handled however Grieg thought best, “but there must be devilry in it!” The result was shrill music inspired by actual cattle calling from the Norwegian mountains, and Grieg invites the women of the chorus to shriek and cry, and not worry about musical correctness: “I think it should sound absolutely diabolical.…Of course, you will have a bad time with the singing, because women singers…think it’s beneath their dignity to sing such stuff, and actresses, I suppose, haven’t the vocal resources. But there must be life in it—that’s the main thing!”

In the herd girls number, authenticity veers into parody. In the Dance of the Mountain King’s Daughter it arrives there, with Grieg declaring, “I have written something…which smacks so much of cow dung, ultra-Norwegianism and self-satisfaction that I quite literally cannot bear to listen to it. But I imagine that the irony will also be apparent, especially when afterwards Peer Gynt, against his will, is forced to say: ‘I swear the dance and the music are, by God, quite beyond compare.’” (What Peer actually says is “Both the dance and the music were utterly charming, the cat will claw me if I dare say anything else!”)

Grieg seems to have had mixed feelings about his Peer Gynt music. He underestimated how much work it would be when he agreed to the commission, and it turned out to be like a Wagner opera, but with trolls instead of Rhine maidens. He was often dismissive about the project, but he also took great pains to integrate the music with the drama and to respect Ibsen’s intentions. There were practical issues, such as the size and quality of the theater orchestra, and in the end, Grieg didn’t attend the rehearsals or the premiere. But he is also on record as saying he’d like to live long enough to see the music “fully performed, and just like I imagine it in my mind.”

So how did Grieg imagine it in his mind? Some things would be certainties. Grieg wanted to hear his music performed by a full-size orchestra with the best musicians. (We can manage that!) And he left many detailed instructions. We know when the music should sound devilish, and when it should have a comic effect. We know Grieg wanted a gong that would sound “as if heaven and earth were being destroyed.” We know he hoped each of the Arabian dancing girls would have her own tambourine because the sound he had in mind could only be obtained in that way. We know he thought of Anitra’s Dance as quiet and delicate, and he hoped the conductor would “treat it like a little pet.” (Never mind that a Bedouin woman is dancing a Polish mazurka.) We know that Solveig’s songs must sound like folk songs.

We also know Grieg wanted a “murderous noise” for the shipwreck. And when Peer’s journey is at an end, and Solveig is singing her lullaby, the music should give the effect of sunrise and the sun breaking through until the last stanza, which is to be performed broadly and tenderly. Solveig’s cradle song makes a devastating conclusion to this fantastic story. Peer is old and dying; Solveig is singing her last song, having waited for him all her life. It’s in Solveig’s devotion that we find the real power in this story about a liar and a rogue, and it’s impossible to remain unmoved.

Yvonne Frindle © 2011/2025

| First performances | Ibsen’s play received its premiere with Grieg’s music on February 24, 1876, at the Norwegian Theater in Christiana (now Oslo), Norway; Grieg did not attend; Bill Barclay’s production was premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in October 2017 |

| First SLSO performances | Suite No. 1 on January 14, 1906, conducted by Alfred Ernst; Suite No. 2 on February 18, 1912, conducted by Max Zach; this is the first time the SLSO has performed the incidental music in its (near) entirety |

| Most recent SLSO performances | Suites No. 1 and No. 2 on February 24, 2002, conducted by Eri Klas |

| Instrumentation | soprano, chorus; piccolo, 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, organ, strings. This production also calls for Hardanger fiddle and 8 actors covering 21 roles. |

| Approximate duration | 2 hours and 10 minutes, including intermission |

Artists

Bill Barclay

Director, writer, and composer Bill Barclay is best-known for creating more than 20 innovative productions of concert–theatre for orchestra. He is Artistic Director of Concert Theatre Works and Music Before 1800, New York City’s oldest early music presenter, and was Director of Music at Shakespeare’s Globe in London (2012–2019), where he produced music for 130 productions and 150 concerts.

Barclay has developed multimedia concerts for venues such as the Hollywood Bowl, Kennedy Center, the Barbican, Buckingham Palace, Shakespeare’s Globe, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Washington National Cathedral, and London’s Southbank Centre. His Broadway and West End credits include Farinelli and the King, Twelfth Night, and Richard III, all starring Mark Rylance.

His projects tour to the world’s leading orchestras, chamber groups, and early music ensembles, including The Chevalier (London Philharmonic Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, Music of the Baroque); Secret Byrd for the Gesualdo Six and Fretwork (20 cities); Antony & Cleopatra (Los Angeles Philharmonic, BBC Symphony Orchestra); and Peer Gynt (Cincinnati and Milwaukee symphony orchestras). Other projects include directing the Silkroad Ensemble on tour, Beyond Beethoven 9 for Marin Alsop, Four Seasons Reimagined for Max Richter and puppeteers Gyre & Gimble, 1791: Mozart’s Last Year for the National Symphony Orchestra, and Letters to a Young Poet for the Brodsky Quartet.

As a composer, he scored Hamlet Globe-to-Globe (189 countries), Call of the Wild (42 American states), and 12 productions for Shakespeare’s Globe. His music has been performed before the British Royal Family, President Obama, the Olympic Torch, and at the United Nations, as well as in refugee camps in Jordan and Calais.

Bill Barclay is a Boston native and past acting company member at Shakespeare & Company (11 years), the Actors Shakespeare Project (10 years, Artistic Associate), and the Mercury Theatre (UK). He trained in Bali, and at the National Theatre Institute and Vassar College, and holds an MFA in Playwriting from Boston University.

Camilla Tilling

Swedish soprano Camilla Tilling (Solveig) is one of the world’s most sought-after concert performers with recent appearances including Mahler’s Fourth Symphony under Gustavo Dudamel (Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Los Angeles Philharmonic), Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder under Esa-Pekka Salonen (London Philharmonia Orchestra), and Beethoven’s Ninth with Gianandrea Noseda (National Symphony Orchestra).

She toured extensively in Peter Sellars’s stagings of Bach’s St Matthew Passion and St John Passion (Berlin Philharmonic and Simon Rattle) and had a special connection to the late Bernard Haitink: singing her first Beethoven Missa Solemnis at Teatro alla Scala under his baton, and performing as his chosen Strauss soloist in his historic final concerts at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw in 2019.

Early operatic roles such as Sophie (Der Rosenkavalier), Pamina (The Magic Flute), Susanna (The Marriage of Figaro), and Zerlina (Don Giovanni) led to house debuts at Royal Ballet and Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Paris Opera, Teatro alla Scala, and the Metropolitan Opera. As Mélisande (Pelléas et Mélisande) she sang at Teatro Real Madrid, Semperoper Dresden, Finnish National Opera, and with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

In the 2024/25 season she sang Bach’s St Matthew Passion (Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Simon Rattle), Mahler’s Rückert Lieder (Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra and Eivind Aadland) and Debussy’s La Damoiselle élue (Sydney Symphony Orchestra and Donald Runnicles), Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été (Norrköpings Symphony Orchestra), Britten’s Les illuminations (Arctic Philharmonic), Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang (Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra), and reprised Daniel Nelson’s Chaplin Songs (Gävle Symphony Orchestra), a work she premiered with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under Andrew Manze. She also returned to the Royal Swedish Opera as the Countess in The Marriage of Figaro, conducted by Alan Gilbert.

Last season, she embarked on a North American recital collaboration with pianist Emanuel Ax, presenting her acclaimed Swedish Nightingale program Jenny Lind: Love and Lieder, and this season she joined Håvard Gimse in the Bergen International Festival with a program of Grieg songs.

Vidar Skrede

Vidar Skrede (Hardanger fiddle) is a performer, composer, producer, and teacher of Nordic folk music. Originally from western Norway, he has been a US resident since 2016 and lives in Milwaukee. He is a multi-instrumentalist performing and teaching fiddle, Hardanger fiddle, guitar, and mandolin. His background is in the traditional music of his home area Rogaland (southwestern Norway). He has learned from a wide array of Norwegian fiddlers and studied at the Norwegian Academy of Music. He also resided in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden as a master’s student of Nordic folk music through the Royal Academy of Music in Stockholm. He has numerous bands, projects, and award-winning recordings to his credit, both in Scandinavia and in the United States. He has toured all the Nordic countries, Scotland, Canada, and the United States, and he has performed with a wide range of notable artists both within his tradition and beyond. Vidar Skrede is a leading musician on the Nordic folk music scene, and is well known for his own tunes, played and recorded by many artists besides himself, and shared among all walks of folk music lovers.

Erin Freeman

A versatile and engaging artist, conductor Erin Freeman has served as the Director of the St. Louis Symphony Chorus since the beginning of the 2024/25 season. She also maintains an international presence through multiple positions and guest conducting engagements. She is Artistic Director of the City Choir of Washington and Wintergreen Music, Resident Conductor of the Richmond Ballet, and Director of Choral Activities at George Washington University.

She recently concluded successful tenures as Director of the award-winning Richmond Symphony Chorus and Director of Choral Activities at Virginia Commonwealth University.

In addition to directing the St. Louis Symphony Chorus, most recently preparing performances of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, recent guest conducting engagements have included Washington Ballet, Richmond Ballet (Carmina Burana for her debut at Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts), and her New York City Ballet debut (George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker); the Toledo, Detroit, Portland (Maine), and Virginia symphony orchestras; Charlottesville Symphony; Buffalo and Savannah philharmonic orchestras; and Berkshire Choral International. In 2023/24, she also made debut appearances at Cadogan Hall, Lincoln Center, and the Vienna Musikverein, and conducted four performances with the City Choir of Washington and three productions with the Richmond Ballet.

She has also conducted at Carnegie Hall, Boston Symphony Hall, La Madeleine in Paris, and the Kennedy Center, and has led and/or prepared the Richmond Symphony Chorus for multiple recordings, including the 2019 Grammy-nominated release of Children of Adam by Mason Bates.

A recent finalist for Performance Today’s Classical Woman of the Year, Erin Freeman has also been named one of Virginia Lawyers Weekly’s 50 Most Influential Women in Virginia. She holds degrees from Northwestern University (BMus), Boston University (MM), and Peabody Conservatory (DMA).

Program Notes are sponsored by Washington University Physicians.