Stravinsky’s Firebird (November 21-22, 2025)

Program

November 21-22, 2025

- Stéphane Denève, conductor

- Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano

Guillaume Connesson (b. 1970)

Maslenitsa

Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978)

- Piano Concerto

- Allegro ma non troppo e maestoso

- Andante con anima

- Allegro brillante

Jean-Yves Thibaudet, piano

Robert Froehner, musical saw (Andante)

Intermission

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)

- The Firebird – Ballet (1910)

- Introduction –

- FIRST TABLEAU:

- Kashchei’s enchanted garden –

- The Firebird appears, pursued by Ivan Tsarevich –

- Dance of the Firebird –

- Ivan Tsarevich captures the Firebird – The Firebird’s entreaties –

- Appearance of the thirteen enchanted princesses –

- The princesses play with the golden apples (Scherzo) –

- Sudden appearance of Ivan Tsarevich – Khorovod (Round dance) of the princesses – Daybreak –

- Ivan Tsarevich enters Kashchei’s palace – Magical chimes,

- Kashchei’s guardian monsters appear and capture Ivan Tsarevich –

- Arrival of Kashchei the Immortal – Kashchei’s dialogue with Ivan Tsarevich Intercession of the princesses –

- The Firebird appears –

- Kashchei’s retinue dances under the Firebird’s spell –

- Infernal dance of all Kashchei’s subjects Berceuse (The Firebird) –

- Kashchei’s awakening – Death of Kashchei – Deep gloom

- SECOND TABLEAU:

- The palace disappears and Kashchei’s spells are broken, the stone knights return to life. General rejoicing

Flame and Fantasy

If a symphony orchestra were a magical creature, it might well be the Firebird of Slavic tradition: marvelous, powerful, and captivating—its sound “burning” so brightly that it can lift spirits, fire the imagination, and light up a concert hall.

The Firebird story Igor Stravinsky and his Ballets Russes collaborators presented to Paris audiences in 1910 was a fantasy twice over: a Russian fairy tale, yes, but an invented one. Rich narrative detail and literal and musical color would give the ballet its own authenticity.

The original Firebird ballet from 1910 isn’t frequently staged, nor is it heard that often in concerts, and you’ll see why: there are 101 musicians on stage (with seven more in the wings). As Stéphane Denève says, “it’s a big, big thing,” but more significant than the “wow factor” of Stravinsky’s music is the mix of culture it represents, and this permeates the whole program.

On one level this concert is very French: conductor, soloist, and our first composer, not to mention The Firebird (L’Oiseau de feu, to use the original name), which Stéphane considers “half-French.” Guillaume Connesson’s Maslenitsa could equally be thought of as half-Russian. The composer describes the music as “old Russia dreamed up by a Frenchman,” and you’ll recognize the flavor of 19th-century Russian music and Orthodox chant. But Maslenitsa isn’t pastiche—Connesson is paying homage, reflecting the poetry of classical traditions he admires.

Another work that’s rarely programmed today is Aram Khachaturian’s Piano Concerto. In fact, until this season, Stéphane himself hadn’t conducted it before. It may be unfamiliar, but we’re confident it will be as exciting in the hands of Jean-Yves Thibaudet as it was at the “electrifying” St. Louis premiere in 1943. The concerto sits at the center of this half- French, half-Russian program as the work of a Georgian-born Armenian, who drew on his own ethnic traditions to craft a distinctive—and irresistible—musical signature. The result is music to lift spirits and fire the imagination in its own way.

Maslenitsa

Guillaume Connesson

Born 1970, Boulogne-Billancourt, France

Stéphane Denève is a champion of Guillaume Connesson’s music, and in recent seasons he has conducted the SLSO in works such as Flammenschrift (Letters of Fire) and, most recently, the US premiere of his violin concerto Lost Horizons. His music continues the great French tradition, says Denève: “richly orchestrated, very colorful…it’s very accessible music of today.”

Maslenitsa is the final installment in a trilogy that began with Flammenschrift. It takes inspiration from the Russian Orthodox feast that precedes Great Lent: Russia’s Carnival time. The feast has both Christian and Pagan origins: a celebration of the end of winter, with blinis as solar symbols, but also the last opportunity for partying before the fasting of Lent. There are masked balls, games, and snowball fights, and on the last day, an effigy of the feast’s mascot, Dame Maslenitsa, is cast into a bonfire.

The music is a symphonic overture in three seamless sections. At first a whirlwind of seven festive themes unfurls before the dance quietens. The central section is like an Orthodox chorale, a meditation on a single theme that grows louder and louder. The festive mood returns in the third section, and the themes overlap, ending with a brass chorale that crowns the piece. “There are no real thematic quotations,” says Connesson. “I wanted to reinvent each theme in the spirit of Russian folk music. This is an old Russia dreamed up by a Frenchman—mingling joy and suffering in homage to this country and this music that I love so much.”

Adapted from a note by the composer © 2025

| First performances | February 9, 2012, in both Bordeaux, France (National Orchestra of Bordeaux Aquitaine, conducted by Alexander Lazarev) and Pau, France (Orchestra of Pau Pays de Béarn, conducted by Fayçal Karoui) |

| First SLSO performance | These concerts |

| Instrumentation | 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 9 minutes |

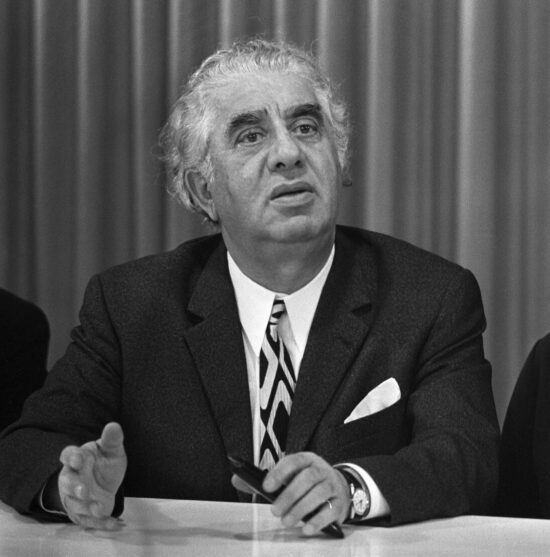

Piano Concerto

Aram Khachaturian

Born 1903, Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Georgia)

Died 1978, Moscow, USSR

Khachaturian’s Piano Concerto is the music of champions. Like Rachmaninoff’s third concerto, or Prokofiev’s second, it takes a champion to play it. At the same time, its place in the repertoire has, more than most concertos, been dependent on individual virtuosos taking up its cause.

As Jean-Yves Thibaudet points out, this concerto is a rarity in today’s concert halls—pianists don’t know it, audiences don’t know it. The SLSO’s own history with the work reflects its shifting fortunes: it was once programmed with respectable frequency, but our most recent performance was nearly 50 years ago. This week, however, Stéphane and Jean-Yves are keen for us to know it, just as Vladimir Golschmann and William Kapell introduced it to St. Louis audiences in 1943, when its Armenian-Soviet composer was relatively unknown.

“Young piano sensation” in the “concerto of the year!” ran the headlines in 1943. As St. Louis critic Francis Klein recalled, Kapell “electrified that audience as it rarely, if ever, had been stimulated.” The occasion was more auspicious than the premiere in Moscow in 1937. That performance had taken place in a windswept park after one rehearsal with a scratch orchestra and the soloist playing an upright piano (or perhaps a baby grand). Even so, Khachaturian’s name was made. More concertos followed, including one for violinist David Oistrakh, as well as the muscular Gayaneh and Spartacus ballet scores.

The Piano Concerto reached New York in 1942 when Maro Ajemian played it with the Juilliard School orchestra. “Khachaturian may displace Tschaikowsky!” exclaimed the New York World-Telegram. Looking for something spectacular to launch his career, Kapell embraced it with fervor, soon acquiring the nickname “Khachaturian Kapell.”

Kapell’s untimely death in a plane crash in 1953 is often blamed for the concerto’s declining popularity. As Washington Post critic Tim Page wrote: “what pianist in sound mind would want to go up against such a formidable ghost?” But there’s another reason. From the outset, this “trashy yet splendidly virtuosic work,” as Virgil Thompson described it in 1942, has been something of a guilty pleasure among music lovers.

Like Lev Oborin, who gave the premiere, listeners are captivated by the concerto’s tempestuous temperament and dazzling virtuosity. Khachaturian’s hallmarks—vibrant colors, compelling rhythms, glamorous folkloric style—are recognizable to anyone who knows the exhilarating Sabre Dance (Gayaneh) or the heart- wrenching Adagio from Spartacus.

The first movement signals a concerto in the grand manner— old-fashioned for the 1930s but ticking Soviet boxes. Its traditional framework introduces two contrasting themes: one edgy and percussive, the other a plaintive evocation of the Armenian folk music in Khachaturian’s heritage. Both come together in a mighty cadenza.

For the Andante, Khachaturian borrowed a popular song from his childhood, slowing it down and making it his own. He changed it so thoroughly his Georgian and Armenian colleagues didn’t recognize the original, but its folk inflections are unmistakable. This movement is made even more alluring by the melting, ethereal sound of the musical saw (a carpentry saw played with a bow). Again, Khachaturian proves he is as capable of great delicacy as he is of vivid drama.

Ultimately, however, this concerto is one of the most physically and technically demanding works in the piano repertoire, especially its tumultuous finale. It’s “heavy,” to use Thibaudet’s word, with an extended cadenza that goes beyond bravura virtuosity to play an important role in the musical development. “It’s all so wonderful, and so exciting to play…and the musicality of it energizes you.”

Yvonne Frindle © 2025

| First performance | July 12, 1937, in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park, with soloist Lev Oborin and conductor Lev Steinberg |

| First SLSO performance | November 27, 1943, with soloist William Kapell and conductor Vladimir Golschmann, in a program celebrating the 10th anniversary of Soviet–American diplomatic relations |

| Most recent SLSO performance | May 12, 1979, with soloist Lorin Hollander and conductor Gerhardt Zimmermann |

| Instrumentation | solo piano; 2 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, musical saw (played by Robert Froehner), strings |

| Approximate duration | 32 minutes |

The Firebird – Ballet

Igor Stravinsky

Born 1882, St. Petersburg, Russia

Died 1971, New York City

Nowadays we’d call it a creative team: Michel Fokine was the choreographer; Léon Bakst devised extravagant costumes, Alexander Golovine a sumptuous set; Sergei Diaghilev was the entrepreneur and visionary. For the 1910 Ballets Russes season in Paris, Diaghilev wanted to create “the first Russian ballet, for there is no such thing as yet.” And with The Firebird his creatives were striving for a harmonious blend of music, design, and dance.

Igor Stravinsky wasn’t Diaghilev’s first choice of composer: Nikolai Tcherepnin, possibly Alexander Glazunov, and Anatol Liadov (famous now for his procrastination) had turned the project down or lost interest. But Stravinsky caught Diaghilev’s attention with his Scherzo fantastique and Fireworks in 1909, then won his confidence when he orchestrated two numbers for Les Sylphides. For a young composer, the Firebird commission was a marvelous opportunity. For Diaghilev it was the most daring, and fortunate, artistic risk he ever took.

The Firebird conflates themes from Russian fairy tales such as the Firebird and Ivan Tsarevich, Kashchei the Deathless, and the princesses with the golden apples. Fokine developed the scenario, supporting it with a progressive style of choreography that rejected the formulas of traditional ballet mime in favor of more natural expression. The intricate choreography was matched by costumes and scenery “submerged,” said artist Alexandre Benois, “in uniform luxury.” Anna Pavlova, sought for the title role, had declared Stravinsky’s music impossible; instead Tamara Karsavina won hearts as the Firebird. Fokine danced the role of the prince. But such was the impact of Stravinsky’s score that it threatened to unbalance the collaborators’ miraculous blending of the arts. In its music, wrote Benois, The Firebird had achieved perfection: “Music more poetic, music more expressive of every moment and shading, music more beautiful sounding and phantasmagoric could not be imagined.”

Synopsis with musical landmarks

Ivan Tsarevich pursues the magical Firebird into an enchanted garden belonging to Kashchei the Deathless. He finds her fluttering around a tree bearing golden apples. During their slow pas de deux she pleads for her release; he asks for a feather before agreeing to let her go. Thirteen princesses enter and play with the golden apples (Scherzo). They are under the spell of Kashchei, and one—the Princess Unearthly Beauty, represented by a clarinet—soon she has the watching Ivan under an enchantment of her own. Ivan reveals his presence in a noble horn solo and the princesses invite him to join in a circle dance, a khorovod, with an oboe theme based on a Russian folk tune.

At sunrise they must return to Kashchei’s palace; when Ivan follows he sets off magical alarm bells and is captured by Kashchei’s monsters. About to be turned into stone, he waves the feather, calling on the Firebird, who casts Kashchei and his followers into a trance before hurling them headlong into the Infernal Dance. She moves among the exhausted dancers and with a Berceuse (lullaby) charms them into a profound sleep. This ravishing movement suspends the descending four- note Firebird motif above a lyrical bassoon theme. She then leads Ivan to a casket containing the egg that holds Kashchei’s immortal soul—a kind of Russian horcrux. Ivan dashes the egg to the ground and the princesses and their petrified lovers are released. In the brief second tableau—the betrothal of Ivan and the princess—a horn theme is developed into a majestic hymn of thanksgiving.

Richard Strauss had recommended Stravinsky begin the ballet with a bang, but the young Russian knew how to enchant his audience with low murmurings from the strings setting out mysterious alternations of major and minor thirds. These unsettling harmonies reveal Stravinsky’s debt to Nikolai Rimsky- Korsakov, his teacher. As Rimsky-Korsakov had done in his operas (including Kashchei the Deathless), Stravinsky gives his mortal characters music built from familiar major and minor scales while the supernatural characters are portrayed through artificial scales and highly chromatic music. The flourishing harmonies of the Firebird and Kashchei’s ominous rumblings belong in a different musical world from the noble horn theme that accompanies Ivan Tsarevich’s entrance or the Round Dance of the Princesses, based on a khorovod from Rimsky-Korsakov’s folksong collection.

The best-known numbers from The Firebird are those Stravinsky retained in his suites: the Dance of the Firebird, the Round Dance, the princesses’ Scherzo with its hints of Mendelssohn, the Infernal Dance, and the exquisite Berceuse and Finale. If this ballet was the opera Diaghilev could not afford to produce then these are the “arias.” But a performance of the complete ballet music allows us to hear the most innovative elements in Stravinsky’s score: to continue the operatic analogy, the “recitatives.”

Fokine’s presentational style of dance mime or “choreodrama” required music that illustrated the smallest gesture on the stage. Often improvising while Fokine demonstrated new scenes, Stravinsky devised music that was deliberately formless, relying on a system of recurring musical motifs associated with characters and dramatic situations. This strategy served Fokine’s aim well, although Stravinsky would reject these often lengthy recitative sections (such as the sequence from Sunrise until the Firebird’s reappearance) when he revised the ballet in 1945—he said he found them embarrassing.

With The Firebird, Stravinsky created a ballet score that was sufficiently modern to titillate but never tax its audience. (True—and taxing!—innovation would emerge three years later in the notorious Rite of Spring.) It was the perfect, graceful entry for a composer who had Petrushka, The Rite of Spring, Pulcinella, Apollo, Orpheus, Agon and a little number for a circus elephant waiting in the wings. Well did Diaghilev point him out to Karsavina, saying: “Watch him closely. He is a man on the eve of celebrity.”

Abridged from a note by Yvonne Frindle © 2000/2025

| First performance | The Firebird ballet was premiered on June 25, 1910 in Paris, with Gabriel Pierné conducting the orchestra of the Ballets Russes |

| First SLSO performance | January 4, 1935, for the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, with conductor Antal Doráti; previously the Berceuse with Max Zach (November 15, 1914) and the 1919 suite with Rudolph Ganz (January 12, 1923). The first concert performance of the ballet took place March 3, 1977, Leonard Slatkin conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 3, 2012 (repeated March 10 at Carnegie Hall in New York City), David Robertson conducting |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), piccolo, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets (one doubling E-flat clarinet), bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (one doubling contrabassoon), contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba; an offstage band of 3 trumpets and 4 Wagner tubas; timpani, percussion, 3 harps, celeste, piano, strings |

| Approximate duration | 50 minutes |

Artist

Jean-Yves Thibaudet

Through elegant musicality and insightful interpretations, Jean-Yves Thibaudet has earned a reputation as one of the world’s finest pianists. He is especially known for his diverse interests beyond the classical world, including collaborations in film, fashion, and visual art.

In 2025/26, he appears in concerts and recitals worldwide, performing music from Gershwin and Saint-Saëns to Bernstein’s Age of Anxiety, Scriabin’s Prometheus, and Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie. He is a champion of Khachaturian’s Piano Concerto, and next week he and Stéphane Denève will perform it with the New York Philharmonic. This season he also tours Europe with violinist Lisa Batiashvili and cellist Gautier Capuçon, as well as continuing his focus on Debussy’s Préludes, performing both books in their entirety.

A prolific recording artist, he has recorded more than 70 albums and six film scores, and has received two Grammy nominations, two ECHO Awards, Gramophone awards, and the German Record Critics’ Award, Diapason d’Or, CHOC du Monde de la Musique, and Edison Prize. Recent recordings include Khachaturian (the Piano Concerto with solo piano pieces) and Gershwin Rhapsody with Michael Feinstein. He is the soloist on Dario Marianelli’s recently reissued soundtrack for Pride and Prejudice (2005), certified Gold by the RIAA, and his playing can be heard on the soundtracks for Atonement (Marianelli), The French Dispatch and Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (Alexandre Desplat), and Wakefield (Aaron Zigman). His concert wardrobe is designed by Dame Vivienne Westwood.