Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff (November 1-2, 2025)

Program

November 1-2, 2025

- Stéphane Denève, conductor

- Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider, violin

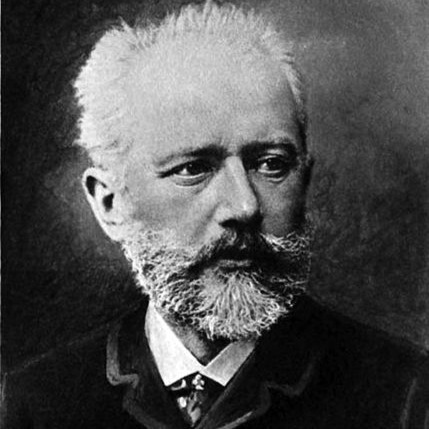

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

- Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

- Allegro moderato

- Canzonetta (Andante)

- Finale (Allegro vivacissimo)

Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider, violin

Intermission

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

- Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27

- Largo – Allegro moderato

- Allegro molto

- Adagio

- Allegro vivace

Passion and Drama

In 1928, at the dawn of music broadcasting, Sergei Rachmaninoff urged music lovers to shun the temptation of comfortable armchairs and radio concerts and head to the concert hall for live performances. “To appreciate good music, one must be mentally alert and emotionally receptive,” he said. “You can’t be that when you are sitting at home with your feet on a chair. No, listening to music is more strenuous than that. Music is like poetry; it is a passion and a problem.” Music was more than listening, he added: witnessing the sight of a virtuoso soloist or an inspired conductor was “almost as thrilling as the sound of the music itself.” Then there was the “powerful contagion in mass emotion.”

Jump forward a century and Rachmaninoff could be speaking about streaming. The competing technologies may have changed, but the experience of live music in all its drama and passion remains as inspiring, as powerful, and as “contagious” as ever.

Rachmaninoff, who lived well into the modern era, is often described as the last Romantic. This isn’t simply a reaction to the luscious harmonies and soaring melodies that seem to belong in the 19th century. There’s an emotional intensity to his music—as Stéphane Denève says, “It’s really love in sounds.”

With the Second Symphony (1908), the 34-year-old Rachmaninoff was named “a worthy successor to Tchaikovsky,” the critic Yuli Engel pointing to the “concentration, sincerity, and subjective delicacy” of his talent and the freshness and beauty of the symphony. “Successor, not imitator,” stressed Engel, “for he already has his own individuality.”

Tchaikovsky’s legacy was melody, not just because his melodies are infused with genius, but because he gave them primacy in everything he wrote. This affords his music an irresistible directness of expression—the drama of emotion. But a concerto introduces another element, the drama of virtuosity, and Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto was so technically innovative for its time that its original dedicatee refused to play it. The critic at the premiere in 1881 had a field day—the concerto was declared “long and pretentious,” Tchaikovsky’s talent “inflated.” The first soloist, Adolph Brodsky, knew better: “one can play it again and again and never be bored.”

Violin Concerto

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born 1840, Votkinsk, Russia

Died 1893, St. Petersburg, Russia

If any composer could compose the music of desire, it was Tchaikovsky. His greatest symphonies suggest a boldly subjective confession of emotions—a trait that has been identified with a particular brand of Romanticism, and a far cry from the ironic detachment that would come several decades later with the first “Moderns,” such as Tchaikovsky’s fellow Russian Igor Stravinsky (who also adored his predecessor). And yet, composers with this level of gift like to challenge themselves, to avoid repeating the same patterns again and again.

The Violin Concerto steps back from the soul-searching attitude of pieces Tchaikovsky composed at the same time. His Fourth Symphony (also 1878), is a score of immense emotional turbulence. In the Violin Concerto, you get the sense of Tchaikovsky putting on a mask, finding relief in the image of the gracious violin virtuoso. It seems to contradict the familiar, scandal-heavy narrative (still much misunderstood) of the composer’s ill-fated attempt to offset gossip about his sexuality. The previous year, he had agreed to marry a lovesick former student, but instantly regretted what he had done—sending his life into chaos, the effects of which spilled over into the Fourth Symphony. Tchaikovsky fled to Western Europe in a temporary exile and took time off in the spring of 1878 to compose his Violin Concerto.

Work on the concerto proceeded at a rapid pace, and it was completed in less than a month. The leisurely and deliciously lyrical result seems at times to suggest pure escapism. Tchaikovsky had long since proved himself one of the masters of melody, and some of the darker undercurrents we find in his other works enter the picture at moments. But in general, the cliché of the hyper-emotive Tchaikovsky here goes on holiday, as it does in some of his other Mediterranean-tinged works. Another factor was Tchaikovsky’s happy discovery of a Spanish- flavored piece by the French composer Édouard Lalo: a quasi-violin concerto known as the Symphonie espagnole. Tchaikovsky especially admired Lalo’s focus on “musical beauty” instead of the routines of “established traditions,” as he put it.

How could the music of Tchaikovsky’s concerto not inspire love at first hearing? Yet his violinist friend (and possible lover) Iosif Kotek refused to play it, despite being the work’s primary inspiration, leading Tchaikovsky to break with him. For complicated reasons, the premiere ended up taking place in Vienna in 1881, in the composer’s absence. On hand to review it was Eduard Hanslick, an eminent critic who made or broke reputations. Hanslick reported a sense of disgust that the Concerto aroused in him, evoking images of “vulgar and savage faces” and “crude curses.” He summed it all up as follows: “It gives us, for the first time, the hideous notion that there can be music which stinks to the ear.”

Fortunately, the Viennese response (perhaps motivated by anti-Russian bias?) turned out to be the exception to the rule. The episode should remind us that musical creation and performance—and its reception by audiences as well as gatekeepers such as critics—never takes place in an ahistorical vacuum but is as subject to passionate, shifting opinions as any political debate.

Listening Guide

Although his own instrument was piano, Tchaikovsky writes for the soloist in a way that maximally explores different aspects of the violin’s personality. What makes this work so enduringly engaging is that it’s by no means all about technical challenges—though there are plenty of those. In the long opening movement, Tchaikovsky turns the violin into a richly complex character, above all an individualist. Commentators have pointed to a more obviously Russian character in the other two movements.

The middle movement (composed in a single day!) is a Canzonetta, which took the place of an earlier effort that the composer decided did not properly fit in the Concerto. The replacement is a simple song with an aura of gentle melancholy that turns the soloist into a virtual vocalist. Tchaikovsky links the Canzonetta without pause to the finale, which bursts on the scene, breaking the soulful spell. We get still another personality here: the fun-loving, earthy fiddler, playing with abandon. Hanslick was revolted by the metaphorical smell of “cheap booze,” but most audiences since that time have been more than happy to be guests at this village party.

Tim Munro © 2019

| First performance | December 4, 1881, Hans Richter conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra with Adolph Brodsky as soloist |

| First SLSO performance | To the best of our knowledge, February 21, 1907, soloist Alexander Petschnikoff and Alfred Ernst conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | March 31, 2019, soloist Karen Gomyo and Jakub Hrůša conducting |

| Instrumentation | solo violin; 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, strings |

| Approximate duration | 36 minutes |

Symphony No. 2

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Born 1873, Semyonovo, Russia

Died 1943, Beverly Hills, California

1907 was a turning point in Sergei Rachmaninoff’s career as a composer. Something of a child prodigy, Rachmaninoff had entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory at age nine and written his first orchestral composition when he was 14. By the time he was 20, he’d completed a piano concerto; an opera, Aleko; several tone poems and chamber pieces; and a number of keyboard works, including the famous Prelude in C sharp minor. The stage seemed set for a lifetime of rich creative accomplishment.

But his artistic progress came to an abrupt standstill in 1897 with the disastrous premiere of his Symphony No. 1, on which he’d pinned much hope. César Cui, the composer and critic, likened the piece to the product of “a conservatory in Hell.” Other commentators were equally harsh. This public failure plunged the composer into a prolonged state of depression and self doubt. During the next three years he continued to conduct and perform as a pianist, but he composed nothing and became so despondent that his friends worried for his health.

Finally, in 1900, Rachmaninoff was persuaded to visit Nicolai Dahl, a doctor specializing in hypnosis. “Incredible as it may sound,” the composer wrote, “this cure really helped me.” Dahl’s then unorthodox therapy must be counted the greatest psychiatric success in the history of music. Rachmaninoff was soon composing again, and he dedicated his Second Piano Concerto to the doctor. Still, he pointedly avoided symphonic writing until 1906, when he resigned his conducting post at the Bolshoi, moved to Germany, and rented a secluded house in Dresden where he could devote his energies to composition. The first work Rachmaninoff completed in Dresden was his Second Symphony, and the enthusiastic reception of its first performances in St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1908 were precisely the success he needed.

Although its most winning quality is its very direct emotional appeal, the Second Symphony is also distinguished by a thoughtful construction, manifested chiefly in the close relationships among its various musical themes. This is particularly true of the first movement, whose introductory slow section (Largo) is based entirely on a brief motto figure presented in the opening measures by the cellos and basses—one of the most satisfying passages in Rachmaninoff’s symphonic output. The fast section that follows (Allegro moderato) also issues from the motto theme. Here the principal melody, heard in the violins over a plaintive clarinet accompaniment, begins with an almost literal rephrasing of the motto, and the graceful second theme develops its “tail” of descending eighth notes.

The melancholy tone of the first movement is replaced in the second (Allegro molto) by a distinctively Russian vigor. The brash opening theme is treated to an ingeniously weaving fugal development, and Rachmaninoff counters this main idea with a more lyrical second subject and a lively, rhythmic central episode. Rachmaninoff plays his strong suit in the slow third movement (Adagio), spinning out the kind of voluptuous melodies at which he excelled. (Eric Carmen borrowed the first of these for his 1975 hit “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again”—it made it to No. 11 in the charts.)

The finale (Allegro vivace) presents a succession of contrasting themes: a playful opening subject, a march-like figure, and a warmly expressive melody for the violins. Towards the conclusion, ideas heard earlier in the symphony are recalled— most notably the motto of the opening Largo and the principal theme of the Adagio—before the whole orchestra erupts in jubilant, tumbling scales that suggest the pealing of Russian bells.

Abridged from a note by Paul Schiavo © 2002

| First performance | February 8, 1908, St. Petersburg, the composer conducting |

| First SLSO performance | December 3, 1915, Max Zach conducting |

| Most recent SLSO performance | October 7, 2017, Leonard Slatkin conducting |

| Instrumentation | 3 flutes (one doubling piccolo), 3 oboes (one doubling English horn), 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings |

| Approximate duration | 60 minutes |

Artists

Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider

Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider is a leading exponent of the violin, with a busy calendar of engagements and an extensive discography. He also brings his violinist’s insight to the podium, and this season marks his sixth as Music Director of the Orchestre National de Lyon.

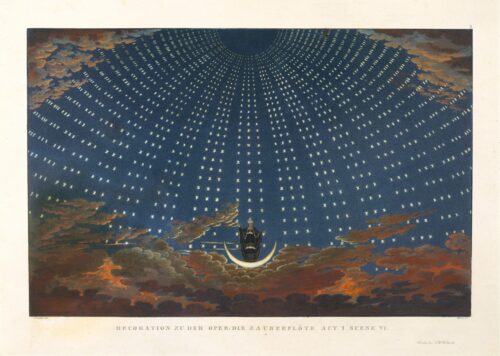

He regularly conducts leading orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, and the London and Chicago symphony orchestras. He also conducts opera, and following his debut in The Magic Flute at the Dresden Semperoper, he was invited to conduct Der Rosenkavalier. Other recent debuts include the Royal Danish Opera, Bavarian State Opera, and Zurich Opera House.

As a virtuoso violinist, this season he returns to the Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Danish National Symphony Orchestra, and New World Symphony, as well as the SLSO.

He has recorded the Mozart concertos with the London Symphony Orchestra, directing from the violin, as well as concertos by Nielsen (Alan Gilbert, New York Philharmonic), Elgar (Colin Davis, Dresden Staatskapelle), Brahms and Korngold (Valery Gergiev, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra), Beethoven and Mendelssohn (Zubin Mehta, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra), Prokofiev and Glazunov (Mariss Jansons, Bavarian Radio Symphony), and Mendelssohn on DVD (Riccardo Chailly, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra). He has also recorded Brahms’ complete works for violin and piano with Yefim Bronfman.

Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider plays the “Kreisler” Guarnerius del Gesu 1741 violin, on extended loan from the Royal Danish Theatre through the generosity of the VELUX Foundations, Villum Fonden, and Knud Højgaard Foundation.